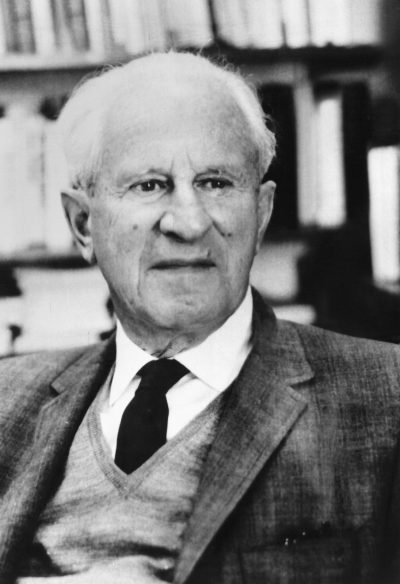

Herbert Marcuse and the End of Utopia

“Even among bourgeois economists, there is hardly a serious thinker who will deny that it is possible, by means of currently existing material and intellectual forces of production, to put an end to hunger and poverty, and that the present state of things is due to the socio-political organization of the world.” — Herbert Marcuse, “The End of Utopia”

This essay outlines the contribution of Herbert Marcuse to political thought by describing his argument against the loaded concept of ‘utopia’, a device which has, through the ages, been used as a synonym for the impossible, to malign radical philosophies as fruitless ventures. Far from being objectively impossible, though, Marcuse saw that socialism was a realizable possibility, repressed by mechanisms of social and political control. In sum, he argued material and intellectual forces could become effective agents of transformation capable of creating a non-repressive society, if only they weren’t trapped in the wrong mode of production, namely industrial capitalism. Marcuse thus sheds new light on the politics of advanced industrial society, and highlights the extent to which forces of orthodoxy will try to contain possibilities for transformation through concepts like ‘Utopia’ which reify the current order.

In July 1967, by then the best known radical philosopher of the day for his incendiary writings on civilization and domination, Marcuse delivered a lecture entitled “The End of Utopia” to the Free University of Berlin. Its purpose was to expose and extinguish what he saw as the false objectivity of contemporary thinking which dismissed utopian philosophies like Marxism as impossible. Because “Any transformation of the technical and natural environment is a possibility“, the New Left luminary observed, a non-repressive life is possible for the masses. An end to alienation and wage labour is possible. We could put an end to poverty and misery. We could be free if only we knew how. But because “the material and intellectual forces which could be put to work for the realization of a free society” are incarcerated in capitalism, they are enlisted in “the total mobilization of the existing society against its own potential for liberation,” a project in which corporations and technocratic elites keep citizens trapped in the horrors of capitalist industrialisation: war, needless consumption, planned obsolescence and waste. The mode of production in advanced industrial society at once contains the potential for its’ own evolution, but has simultaneously evolved to defend itself against those forces which might evolve it.

Whilst proclaiming the obsolescence of the concept of utopia which denotes impossibility, this is also to defend the utopian imagination from its assailants, since it is the spectre of an impossible utopia that engenders its distance and uselessness in the eyes of defenders of the traditional order. As Marcuse sees, the underlying premise of that argument – that socialism is impossible – is contradicted by virtually the entire material and intellectual capabilities of humankind. On top of the conquest of technology over human and nature, of human over nature -symbolized most negatively by the atomic bomb -the exponential “development of productive forces and higher standards of living” in the advanced industrial states signified to Marcuse that the utopian designation for Marx’s theory had ceased to be an operative truth, because the means really existed to rationally plan society in such a way as to create “solidarity for the human species… abolishing poverty and misery beyond all national frontiers and spheres of interest, for the attainment of peace“. Combining a pessimism and optimism he ruminated: “We have the capacity to turn the world in to hell, and are well on the way to doing so.” but concluded that “We also have the capacity to turn it in to the opposite of hell.” He believed technology could make possible creative experimentation with productive forces, which, he hoped, would create a reorganisation of human life in which non-alienated work and nature would be restored to a privileged role, and we would be free to explore our consciousness.

Marcuse wrote against the conventional political wisdom of his age and proved that some of the basic assumptions of the liberal west have become obsolescent to the degree to which their object, namely the ‘utopia’ as the embodiment of a fruitless endeavor, has become obsolescent in social reality. If a socialist vision was to be dismissed as ‘utopian’, then what most people considered ‘realism’ could be called in to disrepute for false objectivity. That is to say ideology, namely the ideologies of instrumental rationality, had concealed the reality of domination and alienation inherent in the structure of industrial societies. Referring to this, Marcuse wrote in 1969 that by taking direct action to prefigure an alternative society based on communism and non-oppressive relationships, the militants had “invalidated the concept of utopia… they have denounced a vicious ideology“. Remarking on “the end of utopia“, in 1967, Marcuse denounced “ideas and theories that use the concept of utopia to denounce certain socio-historical possibilities.” It is open to question, Marcuse thought, whether or not the prevailing positivism and its denial of socialism really represented truth.

Remarking on this he argued “When truth cannot be realized within the established social order,” Marcuse argued, “it always appears to the latter as mere utopia.” What does utopia mean? An unrealisable fantasy, an impossible dream, nowhere we could really live. But that’s only from the point of view of the prevailing reality, which Marcuse takes to be a reflection of a biased positivism. I think Marcuse is at his most incisive here when he rejects the objectivity of a proscribed “reality.”

Because he perceived the possibility of utopia, Marcuse wrote with a view to diagnosing and determining those forces that may bring about radical change. In 1969, writing after the seismic uprising of students and workers in France which revived the egalitarian ideals of the 1871 Paris commune, and against the backdrop of uprising in America, Marcuse evaluated the prospects for rebellion against the abhorrent global order. As a form of acknowledgement of the critical influence of the radicals on the febrile atmosphere of protest worldwide, he hailed, in An Essay on Liberation, that a fresh generation of activists had “proclaimed” an era of “the permanent challenge, the permanent education“… “the great refusal“, a species of rebellion in which, he argued to Adorno a little later, consisted possibilities for “the internal collapse of the system of domination today”. Within Marcuse’s philosophy of liberation, which came to be a highly regarded and influential source of guidance to oppositional movements of the New Left, the goal of radical politics was to establish a non-repressive society “based on a fundamentally different experience of being, a fundamentally different relation between man and nature, and fundamentally different existential relations” to the oppressive ones incarnate in contemporary society. Fledgling protest movements brought this “great refusal” closer to fruition because they mobilised against all manifestations of oppression, because “they recognised the mark of social repression” perpetuated by the dominant institutions of civilisation “even in the most spectacular manifestations of technical progress.” Beneath the illusion of its progress, dissenters had become conscious of all that was wrong with the society they inherited, and they looked out to the world with unease.

Marcuse’s adroit remarks on the backlash against repression, made in the height of the New Left’s activity, reveal his thoughts on liberation in their broader cultural and historical milieu. It was a seismic era, a time of transition: The age of capitalist exploitation and neo-colonialism was increasingly assailed by keen and conscientious citizens who no longer wanted to play the game of society. They wanted to introduce a qualitatively different society, one which trans-valuated – transformed the values of, re-evaluated – the civic order they inhabited. Post-war society was abloom with “a protest against capitalism,” a movement to: transcend its conditions of alienation “which cuts to the roots of its existence,” which argued vehemently “against its henchmen in the Third World,” and despised “its culture, its morality” of wastefulness and nihilism. By this point it had become clear to Marcuse and conscientious pupils that the growth and success of the advanced industrial economies was an expression of a project at the center of which is the “experience, transformation and organization of nature” as well as people “as the mere stuff of domination“. Civilization depended on subjection to tyranny, to entrenched forms of subjugation, exploitation and alienation of the masses and nature. But society at this time was nonetheless incandescent with the idea of change. There was a world to win.

One of the most interesting aspects of Marcuse’s philosophy is that it dealt incisively with the forces of repression that our society continues to generate at that very point in time when it has developed the means for creating a new and liberated society. The movement to disestablish capitalism has been at work for over two centuries. From the start the impetus was – as it still is – revolutionary: inflamed with the rise and fall of social orders, borne up by that sense of living through a revolutionary moment which continues to galvanize the left. The assault on capitalism continues, though the revolution hasn’t taken place, or where it has, has been quickly stifled by counter-revolution. Gradually becoming hoist to the engine of counter-revolution, revolutionary energies are absorbed and defused, whilst capitalism evolves to contain those forces that might evolve it. But as Marcuse reminds us, the possibility of utopia remains very much real.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Featured image: Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo