Laos: The New Cold War Battleground You Don’t Know About

The “New Cold War” could be a potential description for the unfolding geopolitical lay of the planet as Russia reemerges as a world power, and China rises as a new one in the face of a prevailing Wall Street-Washington-London international order.

The most obvious battlegrounds taking shape in this “New Cold War” are Ukraine, Syria, and the South China Sea. Perhaps not as high-profile but no less important are the ongoing conflicts in and around Libya, the proxy war being waged across Yemen, and America’s enduring occupation of Afghanistan in Central Asia.

However, there are other struggles taking place that go virtually unseen by the general public, or are briefly mentioned – out of context in the news – before being quickly forgotten.

Laos – A Pivotal Battleground

For the Southeast Asian state of Laos, this is not the first time it has played a pivotal role in the ongoing struggle between East and West. It was bombed during the Vietnam War by the United States and according to the UN-funded Washington-based “Legacies of War” organization:

…from 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos during 580,000 bombing missions—equal to a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24-hours a day, for 9 years – making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.

Even as US diplomats find themselves today posing for photo opportunities in Laos’ capital, Vientiane, nearly 100 people a year are still killed or injured across the country from unexploded US ordnance.

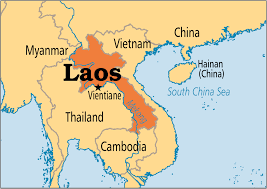

Today, Laos serves as more than a mere extension of the Vietnam War’s battlefield and subsequent legacy. Bordering Myanmar, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand, it is a crossroads between much of Southeast Asia as well as the gateway into East Asia.

Though landlocked, Laos possesses immense hydroelectric potential – potential that has been incrementally developed through cooperation with Beijing. Not only do dam projects help manage water resources and provide electricity for the people of Laos, it has allowed Laos to become an increasingly important source of alternative energy for its neighbors as well.

In developing Laos’ potential as a gateway between Southeast Asia and East Asia, China has undertaken or begun planning several massive infrastructure projects across its territory including highways and railways. Thailand has also played a role in developing Laos’ infrastructure. It has invested in a China-Laos-Thailand highway connecting the three nations, as well as constructed Laos’ first rail station across the border from Nong Khai, Thailand.

In the capital Vientiane itself, one will find both Chinese and Thai businesses investing in the city. And because Thailand and Laos share linguistic similarities, much of the media consumed in the capital is streaming directly from Thailand.

It would seem then, despite the destruction it suffered at the hands of the United States decades ago, it is slowly on its way back up, and thanks to strengthening ties with its neighbors.

America’s Proxy War with China

While called the “Vietnam War,” in reality, Washington’s war in Vietnam was but a part of a larger proxy war aimed at encircling and containing China. Exposed in the Pentagon Papers in the early 1970’s, three important quotes from these papers would reveal this strategy.

It states first that:

…the February decision to bomb North Vietnam and the July approval of Phase I deployments make sense only if they are in support of a long-run United States policy to contain China.

It also claims:

China—like Germany in 1917, like Germany in the West and Japan in the East in the late 30′s, and like the USSR in 1947—looms as a major power threatening to undercut our importance and effectiveness in the world and, more remotely but more menacingly, to organize all of Asia against us.

Finally, it outlines the immense regional theater the US was engaged in against China at the time by stating:

…there are three fronts to a long-run effort to contain China (realizing that the USSR “contains” China on the north and northwest): (a) the Japan-Korea front; (b) the India-Pakistan front; and (c) the Southeast Asia front.

While the US would ultimately lose the Vietnam War and any chance of using the Vietnamese as a proxy force against Beijing, the long war against Beijing would continue elsewhere. This includes all of Southeast Asia today, with US attempts to put in place client regimes in Myanmar through Aung San Suu Kyi’s political front, Anwar Ibrahim’s in Malaysia, Thaksin Shinawatra’s in Thailand, continued subjugation of the Philippines which had existed as a US territory for nearly half a century (1898-1946), and of course, through more subtle political subversion in Vietnam itself.

Target Laos

What will strike any visitor to Laos’ capital of Vientiane is not just the incremental progress being made by Chinese and Thai development, or the expansion and evolution of Laos state enterprises, but also the vast number of Western-funded NGOs present. Besides their numerous offices, SUVs with NGO logos affixed to the doors, and scheming agents muttering in the corners of Vientiane’s many cafes, there is no actual evidence of any positive impact they are making.

The role of these NGOs besides building networks and cultivating collaborators, is to leverage social and environmental facades to oppose the construction of infrastructure across the country – especially dams and transportation projects. The goal is to cut off China and preserve Laos’ natural and human resources for development by Western corporations who, so far, have been late to the game.

A similar formula has been used in Myanmar, where NGO opposition to dams in conjunction with armed groups attacking construction sites helped delay or cancel many projects that may have transformed Myanmar for the better. The war on Laos has gone from mass bombing to mass propaganda, with US-backed NGOs coordinating activities both in Laos and in neighboring countries pressuring the government in Vientiane to delay or cancel dams that were to be built in cooperation with Beijing.

Protesters paradoxically claim that the dams will disrupt both the environment and traditional fishing communities along rivers downstream from dams. Traditional fishing communities, however, are generally synonymous with both unsustainable environmental destruction and poverty. Conversely, environmental impacts by dam construction can be mitigated through careful planning, while working to lift surrounding communities and the nation as a whole from poverty through improved infrastructure and cheaper and more accessible energy.

Protesters are not campaigning for careful planning, or better oversight of projects, they are campaigning instead for arrested development for Laos and its people – the sort of campaign only Wall Street and Washington could benefit from.

Strangling Development

The impact China and Thailand have had on Laos is self-evident. The roads under ones feet were put there by Chinese construction firms, power running through the wires fed by dams built by joint Lao-Chinese ventures, and a burgeoning economy built upon closer cooperation between Laos and its neighbors, particularly China and Thailand. What the US and those nations in Southeast Asia it is slowly turning against Beijing have done for Laos is more difficult to enumerate – perhaps because there is nothing to enumerate.

A recent article published by The Diplomat titled, “Leadership Change in Laos: A Shift Away From China?,” attempts to frame recent political developments in Laos as a potential shift in influence away from Beijing and in favor of Vietnam as well as the international community (read: the West). In reality, the author fails categorically to enumerate what influence Vietnam has in Laos and through which vectors other than speculative political affiliations of outgoing and incoming politicians in the Laotian government, that influence moves.

The Diplomat claims:

Analysts said the changes will give Vietnam an edge in its dealings with Laos. Hanoi has been angered by Thongsing’s plans for massive dam construction projects across the Mekong River and its tributaries which scientists say will impact badly on fish production and food security.

“That new slate at the top of the secretive one-party state are all viewed to be pro-Hanoi while those who are exiting have been allied with the Chinese,” RFA said in its dispatch.

Speculation is also rife that the Mekong River Commission (MRC) – which has lost the support of many international donors – will be forced to relocate out of Laos after claims the government had abused its base in Vientiane to push for the widely unpopular dam construction program.

It appears, at least from a Western point of view, that it is hoped Laos’ government will move away from not only its ties to China, but away from all development driven by these ties as well.

However unlikely that is to happen, understanding the role NGOs play in arresting, not catalyzing development, and the role they play in a wider US strategy to encircle and contain China – at the expense of the nations it plans on using as proxies to execute containment – is key to exposing them and flushing them out of Southeast Asia.

China is an immense nation with equally immense potential. It plans on escaping Western containment policies aimed at it for over a half century by bringing the rest of Asia up with it as it rises as incentive for cooperation against containment. To combat this, the US and its NGOs are determined to cut the ropes China has lowered down to its neighbors – while providing no viable alternative for Southeast Asia to hold onto except for domineering “free trade agreements,” entangling and costly military alliances, and perpetual political meddling within each respective state.

Considering the lopsided nature of incentives to cooperate with China versus US attempts to dissuade cooperation, and despite the wishful thinking exhibited by publications like The Diplomat, it is no wonder that despite penning a containment policy as early as the 1940’s, the US has failed to impede China’s progress or effectively create a united front against China in Southeast Asia.

For readers, the next time anti-dam protests make the headlines, they will know who is behind them, and why.

Tony Cartalucci, Bangkok-based geopolitical researcher and writer, especially for the online magazine“New Eastern Outlook”.