Jamaica: Marcus Garvey’s Economic Philosophy Has a “Capitalism Problem”

Featured image: Marcus Mosiah Garvey (Source: Bio.com)

The controversy surrounding the May 19th unveiling of a bust of Jamaica’s first national hero and Pan-Africanist Marcus Mosiah Garvey on the Mona Campus of the University of the West Indies (UWI) has led some Garveyites and Pan-Africanists to call for the study and use of his philosophy in the service of African liberation.

Garveyites are up in arms about the Raymond Watson’s created bust of Garvey that bears no resemblance to the most common photographic (re)presentations of this exponent of African Nationalism and racial uplift.

Retired UWI professor and organic intellectual Carolyn Cooper captures mass sentiments on this bust when she states in the article “Taking Liberties with Marcus Garvey” that:

Raymond Watson’s image of Garvey reveals nothing of the authority, passion and power of more full-bodied representations of our national hero. I wouldn’t go as far as cancer. But Garvey seems poorly. His posture conveys passivity. He looks like a weakling. Who approved this diminished portrayal?

Professor Archibald McDonald, pro-vice-chancellor and principal of UWI praised the legacy of Garvey’s anti-colonial, anti-racist and African liberation legacy.

At the ceremony marking the launch of the bust, Professor McDonalds stated that

“In supporting the realisation of this monument to be unveiled, it is our hope that students, faculty members, and visitors to the campus will see a vision of self, one of greatness that breaks the mental and physical chains of oppression that try to tell us that we are anything but worthy and proud.”

However, we cannot use Garvey’s message of liberation to break “mental and physical chains of oppression” without acknowledging and discussing the fact that Marcus Garvey’s philosophy has a capitalism problem.

Statue of Marcus Garvey in the University of the West Indies (Source: Jamaica Observer)

When many Pan-Africanists engage in conversations about Marcus Garvey and the achievements of his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), they usually express unbridled praise for the economic development approach of the organization and its founder. But the devil is always in the details.

Marcus Garvey was born on August 17, 1887 in a racist, colonial environment that was hostile to the interests of African-Jamaicans. During the years 1910-1914, Garvey travelled to a number of countries in Latin America and Europe and this experience brought a high level of awareness of the exploited condition of Africans. Garvey created the UNIA in July 1914 in Jamaica and went to the United States in March 1916.

The United States became the organization’s headquarters and prime site of its success and failure. According to Garvey in the book “The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey” by 1921 the UNIA had “900 branches and with an approximate membership of 6,000,000.” Garvey’s claim about the number of members has not been independently confirmed.

Garvey’s commitment to self-reliance and liberation of the global African community led him to place a strong emphasis on business development. In “Philosophy and Opinions” Garvey declares that,

“Chance has never yet satisfied the hope of a suffering people. Action, self-reliance, the vision of self and the future have been the only means by which the oppressed have seen and realized the light of freedom.”

Self-reliant economic development is actually a key element of an oppressed group’s strategy to develop the alternative economic institutions and practices today, which will serve as the seeds of the liberated society of tomorrow. Collective self-reliance will bolster the extent to which an oppressed group or country is able to withstand the pressure or punishment of its enemies.

In the promotion of self-reliance and economic development, Garvey presented a compelling vision of racial upliftment to the labouring classes. He believed that the African working-class could be mobilized behind an anti-colonial project. C.L.R. James remarked on Garvey’s ability to inspire and organize the Afrikan masses:

He deliberately aimed at the poorest, most down-trodden and humiliated Negroes. The millions who followed him, the devotion and the money they contributed, show where we can find the deepest strength of the working class movement, the coiled springs of power which lie there waiting for the party which can unloose them.

Even before the independence movements or national liberation struggles in Africa and the Caribbean, Garvey demonstrated the possibility of bringing the people onto the stage of history. However, retired UWI Professor Rupert Lewis and Garvey expert reported in his text “Marcus Garvey: Anti-Colonial Champion” that the now defunct Workers Party of Jamaica saw the Garvey movement as an ‘alliance of the proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie albeit under petty bourgeois leadership.’

In the effort to ‘create a new people,’ Garvey practised a race-first economic development framework. The late Garvey scholar Tony Martin provides a scope of the UNIA’s portfolio of businesses in his book “Race First: The Ideological and Organizational Struggles of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Improvement Association.” The UNIA operated laundries, tailoring business, grocery stores, printing press, doll making company, the Negro World newspaper, a hat making establishment, shipping company, restaurants and a hotel. It had assets such as trucks and buildings and hundreds of employees.

The range of businesses operated by UNIA is still impressive to many Pan-Africanists, but they are not mindful of the lessons that should be learned from the UNIA and Garvey’s business practices.

W.E.B. Du Bois’s article “Marcus Garvey” in the book “Marcus Garvey and the Vision of Africa” outlines Garvey and the UNIA’s lose financial management practices, inexperience in the shipping business that led to buying unworthy ships at inflated prices, Garvey’s top-down management and leadership style, no knowledge of the “investment of capital and (Garvey had) few trained and staunched assistants” to operate the Black Star Line, the flagship enterprise of the UNIA.

In spite of the positive elements of economic Garveyism, it is not appropriate for African liberation in the 21st century. Many current Garveyites tend to ignore the fact that Garvey’s economic development approach was based on reproducing the exploitative system of capitalism, which would continue to oppress the Afrikan working-class.

Our engagement with capitalism, as enslaved Africans and wage-slaves today, provides us with lived experience of this economic system that puts profit before the needs of the people. Furthermore, capitalism enables the ruling-class minority to economically, socially and politically dominate the working-class majority.

Garvey was quite insistent that capitalism was the path to economic development. In the book “Message to the People: The Course of African Philosophy,” he had this to say about capitalism:

“As a fact, the capitalist of today was the labourer or worker of yesterday…. Hence, the man who wants to go into business commercially, industrially or agriculturally, and win a fortune for himself, cannot and should not be a Communist, because Communism robs the individual of his personal initiative and ambition or the results thereof. Democracy (interchangeable with capitalism), therefore, is the kind of government that offers the individual the opportunity to rise from a labourer to the status of a capitalist or employer.”

In “Philosophy and Opinions” Garvey asserts that,

“Capitalism is necessary to the progress of the world, and those who unreasonably and wantonly oppose or fight against it are enemies to human advancement.”

Garvey naively called for the state to place constraints on “capitalistic interests.” He might have been unaware of the fact that the state serves and protects the interests of the economic elite.

Du Bois’s “new economic solidarity” proposal of the 1930s is still relevant to Afrikan liberation. It called for the creation of a network of consumer cooperatives in order to meet the need of Afrikan-Americans for goods, services and employment. Du Bois promoted his programme as a way to advance Afrikan political empowerment and challenge the dog-eat-dog system of capitalism. You may explore Du Bois’s cooperative economic thoughts in “A Negro Nation Within the Nation” in the book “W.E.B. Du Bois Speaks: Speeches and Addresses, 1920-1963.”

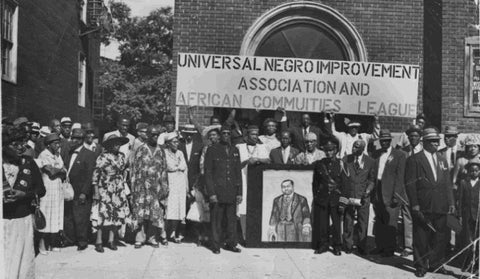

After Garvey’s return to Jamaica he decided to organize the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association) and was joined by tens of thousands Afro American. (Source: Weblackspirit)

Garveyites and other Pan-Africanist must place the question of the destruction of capitalism at the centre of their organizing programme for African liberation. Such a course of action calls for the recognition of class division within the African race and the need for us to recognize the class struggle between the African labouring classes and African capitalist exploiters.

Our interrogation and critique of Garvey’s capitalism problem does not repudiate useless elements within his outlook on African liberation. We are simply disassociating ourselves from his enthusiastic support for capitalism that is the enemy of the African working-class in Africa and throughout the African Diaspora.

Capitalism is incompatible with human progress and emancipation. Therefore, all people of good conscience must commit themselves to casting this barbaric and soul-destroying economic system into the cesspool of history.

On the matter of the UWI’s Garvey bust, the intense and widespread opposition to this sculpture has led to UWI’s commitment to take it down and replace it with a bust that is reflective of a realistic representation of the Garvey that exists in the popular imagination.

We should not allow this controversy to go to waste. Revolutionary Pan-Africanists and progressive Garveyites should use it to explore a transitional economic development path that rejects capitalism and embraces the self-organization of the labouring classes in the economic, social, cultural and political spheres.

Rupert Lewis offers a challenge to the folks who are focused on how close the statue resembles Garvey as well as UWI’s administrators to address a more concrete question that has relevance to the labouring classes in Africa and the Caribbean.

Lewis asserts that

“Our focus should be centred on the creation of programmes within the UWI that can tackle the development problems of Africa and the Caribbean in the 21st century.”

Many of us are too fixated on symbols and the seductiveness of one-off protest actions, which do not demand the time, dedication and commitment that come with organizing in membership-based organizations with regular programmes, projects and/or an institution-building mandate.

*This essay is an expanded version of an earlier one that appeared in the Canadian based newspaper Share.

Ajamu Nangwaya, Ph.D., is a writer, organizer and educator. Ajamu is a lecturer in the Institute of Caribbean Studies at the University of the West Indies.