Israel’s Army and Schools Work Hand In Hand, Say Teachers

Close ties mean Israeli pupils are being raised to be ‘good soldiers’ rather than good citizens

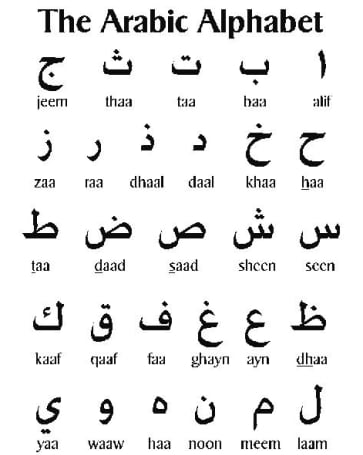

The task for Israeli pupils: to foil an imminent terror attack on their school. But if they are to succeed, they must first find the clues using key words they have been learning in Arabic.

Arabic lesson plans for Israel’s Jewish schoolchildren have a strange focus.

Those matriculating in the language can rarely hold a conversation in Arabic. And almost none of the hundreds of teachers introducing Jewish children to Israel’s second language are native speakers, even though one in five of the population belong to the country’s Palestinian minority.

The reason, says Yonatan Mendel, a researcher at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem, is that the teaching of Arabic in Israel’s Jewish schools is determined almost exclusively by the needs of the Israeli army.

Mendel’s recent research shows that officers from a military intelligence unit called Telem design much of the Arabic language curriculum. “Its involvement is what might be termed an ‘open secret’ in Israel,” he told MEE.

The military are part and parcel of the education system. The goal of Arabic teaching is to educate the children to be useful components in the military system, to train them to become intelligence officers.

Telem is a branch of Unit 8200, dozens of whose officers signed a letter last year revealing that their job was to pry into Palestinians’ sex lives, money troubles and illnesses. The information helped with “political persecution”, “recruiting collaborators” and “driving parts of Palestinian society against itself”, the officers noted.

Mendel said Arabic was taught “without sentiment”, an aim established in the state’s earliest years.

The fear was that, if students had a good relationship with the language and saw Arabs as potential friends, they might cross over to the other side and they would be of no use to the Israeli security system. That was the reason the field of Arabic studies was made free of Arabs.

Officers in classroom

The teaching of Arabic is only one of the ways the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), as the Israeli military is known, reaches into Israeli classrooms, teachers and education experts have told MEE.

And many fear that the situation will only get worse under the new education minister, Naftali Bennett, who heads Jewish Home, the settler movement’s far-right party.

Most Jewish children in Israel are subject to a military draft when they matriculate from high school at the age of 17. Boys usually serve three years, and girls two.

However, the army and the recent rightwing governments of Benjamin Netanyahu have been concerned at the growing numbers who seek exemptions, usually on medical, psychological or religious grounds.

Nearly 300 schools have been encouraged to join an IDF-education ministry programme called “Path of Values”, whose official goal is to “strengthen the ties and cooperation between schools and the army”.

In practice, say teachers, it has led to regular visits to schools by army officers as well as reciprocal field trips to military bases for the children, as a way to encourage them to enlist when they finish school.

Although what takes place during visits is rarely publicised, the Israeli media reported in 2011 that on one simulated shooting exercise children had to fire their weapons at targets wearing a keffiyeh, or traditional Arab headdress.

Militarism is in every aspect of our society, so it is not surprising it is prominent in schools too,” said Amit Shilo, an activist with New Profile, an organisation opposed to the influence of the army on Israeli public life.

We are taught violence is the first and best solution to every problem, and that it is the way to solve our conflict with our neighbours.

Fear of being sacked

MEE has had to conceal the identities of the teachers it spoke to, because the education ministry requires pre-approval of any interviews with the media.

Most of the teachers were concerned that they might be sacked if they were seen to be criticising official policy.

All the teachers noted that schools have come under mounting pressure to actively participate in the IDF programme.

Each school is now graded annually by the education ministry not only on its academic excellence but also on the draft rate among pupils and the percentages qualifying for elite units, especially in combat or intelligence roles.

Schools with a high draft rate can qualify for additional funding, said the teachers.

Ofer, a history teacher in the centre of the country, said: “When it comes to the older children, you have to accept as a teacher that the army is going to be inside the school and in your classroom. All the time the students are being prepared for conscription.

The army is treated as something holy. There is no way to speak against the army at any point.

Rachel Erhard, an education professor at Tel Aviv University, recently warned that Israel’s schools risked becoming like those of Sparta, the city in ancient Greece that famously trained its children from a young age to be warriors.

Public hounding

There are additional pressures on principals to participate, note teachers.

Zeev Dagani, head teacher of a leading Tel Aviv school who opted out of the programme at its launch in 2010, faced death threats and was called before a parliamentary committee to explain his actions.

The public hounding of teachers who oppose the militarisation of Israel’s education system, or are simply active outside the classroom in opposing the occupation, has continued.

Adam Verete, a Jewish philosophy teacher at a school in Tivon, near Haifa, was sacked last year after he hosted a class debate on whether the IDF could justifiably claim to be the world’s most moral army.

As the new school year started this month, parents and city mayors launched high-profile campaigns against two teachers for their anti-occupation views.

Avital Benshalom, who had just taken up her new post as head of the School of the Arts in Ashkelon, was forced to issue an apology for signing a petition 13 years ago supporting soldiers who refused to serve.

Herzl Schubert, a history teacher, similarly found himself facing a storm of protest after he was filmed taking part in a West Bank demonstration in support of the Palestinian village of Nabi Saleh during the summer vacation.

Notably, neither Bennett nor Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu intervened to support the two teachers’ right to free speech.

Racist depictions

Teachers and education experts who spoke to MEE said such incidents had created a climate of fear that was intended to intimidate other teachers.

Neve, a history teacher at a school near Tel Aviv, said: “Teachers are afraid to speak out. The pressure comes not just from the education ministry but from pupils and parents too. The principals are terrified something bad will happen to the school’s reputation.”

The education ministry declined to respond to the accusations.

Teachers and education experts point to examples of collusion between schools and the IDF in all aspects of the education system.

Nurit Peled-Elhanan, a professor of education at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, said her studies of Israeli textbooks showed depictions of Arabs and Palestinians were “racist both verbally and visually”.

“They are necessary to legitimise a Jewish state, the history of massacres of Arabs, discrimination against Palestinian citizens and a lack of human rights in the occupation territories,” she told MEE.

The aim is to create good soldiers, those who are prepared to torture and kill and still think they are doing the best for the nation.

Separate studies of maps in textbooks have shown three-quarters do not indicate the Green Line separating Israel from the occupied Palestinian territories, suggesting the whole area accords with the right’s idea of Greater Israel.

Revital, an Arabic language teacher, said the army’s lesson plans were popular with pupils. “I don’t approve of them, but the students like them. They celebrate and laugh when they kill the terrorists.”

Revital said she had been disciplined for speaking her mind in class and was now much more cautious.

“You end up hesitating before saying anything that isn’t what everyone else is saying. I find myself hesitating a lot more than I did 20 years ago. There is a lot more fascism and racism around in the wider society,” she said.

Holocaust studies

Some of the close ties between the IDF and the education system are well known.

The education ministry funds several prestigious schools, such as the Reali in Haifa, whose students combine education with military training as cadets.

Ofer said many senior teachers and principals were recruited directly from the army, when they retired at 45. “They then go on to a second career instilling ‘Zionist values’ into the students,” he said.

But the examples of overtly militarised education tend to overshadow the more subtle engineering of the curriculum of ordinary schools, complain teachers.

There are particular concerns about the emphasis in the curriculum on the Holocaust, including a decision last year to extend mandatory Holocaust studies to all ages, including kindergartens.

Following objections from the small leftwing Mertz party, the then education minister, Shai Piron, instructed kindergartens that soldiers should not bring guns into the classroom to ensure children’s safety.

Meretz legislator Tamar Zandberg, however, observed that uniformed soldiers should not be in kindergartens in the first place.

“People see inserting the army into the educational system as something natural, and it’s time that the educational system internalized the fact that its place is to educate to civic values,” she said.

Neve said the students no longer learnt about human rights or universal values in history classes.

Now it’s all about Jewish history – and the Holocaust is at the centre of it.

When we take the children to the deaths camps in Poland, the message is that everyone is against the Jews and we have to fight for our survival. They are filled with fear.

The conclusion most draw is that, if we had had an army then, the Holocaust could have been stopped and the Jewish people saved.

Atmosphere of fear

The teachers said an atmosphere of fear and sense of victimhood dominated classrooms and translated into a young generation even more rightwing than their parents.

David, who teaches computer sciences in a Galilee school, said: “You have to watch yourself because the pupils are getting more nationalistic, more religious all the time. The society, the media and the education system are all moving to the right.”

A 2010 survey found that 56 per cent of Jewish pupils believed their fellow Palestinian citizens should be stripped of the vote, and 21 per cent thought it was legitimate to call out “Death to the Arabs”.

Subjects that have become particularly vulnerable to the promotion of military values, according to teachers, are Arabic, history and civics.

Naftali Bennett brought in a new head of civics in July. Asaf Malach is a political ally who believes the Palestinians should not be allowed a state.

A history lesson plan proposed last year, shortly after Israel’s 51-day attack on Gaza that left at least 500 Palestinian children dead, encouraged pupils to be “Jewish fighters”, modelling themselves on the Biblical figure of Joshua.

But Revital said most teachers were not concerned by these developments. “Out of the 100 teachers in my school, maybe two or three think like me. The rest think it’s important the army are in the school.”

Among those is Amit, who teaches Judaism in central Israel. He said: “Inviting soldiers into the classroom is not just about encouraging the students to enlist but for us to talk about the value of solidarity and the contribution every person can make to society.

Our job is to prepare them for future challenges, and that includes the army. We can’t ignore the reality that we live in a country where there are soldiers everywhere.

Neve, however, said hopes of ending Israel’s conflicts in the region depended on bringing a more civilian ethos back into schools.

If our students don’t learn about others’ history, about the Palestinians, then how can they develop empathy for them? Without it, there can be no hope of peace.