Israeli Nuclear Weapons Program: Israel’s Quest for Yellowcake – The Secret Argentine-Israeli Connection, 1963-1966

While Prime Minister Netanyahu points to the threat of Iran’s non-existant nuclear weapons program, amply documented Israel has developed an advanced nuclear arsenal, in defiance of international law.

The following documents released by the National Security were first published by Global Research in July 2013. (M.Ch, GR Editor).

Previously Secret Documents Show That Canadian Intelligence Discovered That Israel Purchased Yellowcake from Argentina in 1963-1964

Information Later Shared with British and Americans, Who Accepted It after Hesitation

U.S. State Department Insisted that Uranium Sales Required Safeguards to Assure Peaceful Use but Israel Was Uncooperative and Evasive About the Yellowcake’s Ultimate Use

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 432

For more information contact:

William Burr: [email protected]

Avner Cohen: [email protected]

For more documents on the Israeli nuclear weapons program, see “Israel and the Bomb,” documents edited by Avner Cohen.

William Burr, National Security Archive, and Avner Cohen, James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, editors

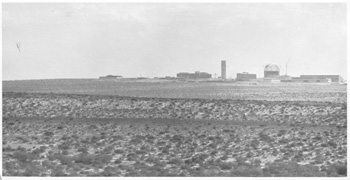

Image: This and the three other photographs of the construction site near Dinoma in the Negev desert for Israel’s then-secret nuclear reactor were taken during 1960. It is difficult to identify precisely who took these photos, but information in a draft U.S. Intelligence Board post-mortem strongly suggests that British and U.S. military attachés took the photos. It is likely that these are the photographs described on pages 13 and 14 of that report. The plainly visible reactor dome undermined Israeli claims that a textile factory was under construction. These images of the reactor site, some of them classified secret or confidential, are located in State Department records at the National Archives. (Record Group 59, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary of State for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy, 1948-62, box 501, Country File Z1.50 Israel f. Reactors 1960)

During 1963-64, the Israeli government secretly acquired 80-100 tons of Argentine uranium oxide (“yellowcake”) for its nuclear weapons program, according to U.S. and British archival documents published today for the first time jointly by the National Security Archive, the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project, and the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey institute of International Studies (MIIS). The U.S. government learned about the facts of the sale through Canadian intelligence and found out even more from its Embassy in Argentina. In response to U.S. diplomatic queries about the sale, the government of Israel was evasive in its replies and gave no answers to the U.S.’s questions about the transaction.

These nearly unknown documents shed light on one of the most obscure aspects of Israel’s nuclear history-how secretly and vigorously Israel sought raw materials for its nuclear program and how persistently it tried to cultivate relations with certain nuclear suppliers. Yellowcake, a processed uranium ore, was critically important to Israel for fuelling its nuclear reactor at Dimona and thereby for producing plutonium for weapons. The story of the Argentine yellowcake sale to Israel has remained largely unknown in part because Israel has gone to great lengths to keep tight secrecy to this day about how and where it acquired raw materials for its nuclear program.

That Argentina made the yellowcake sale to Israel has already been disclosed in declassified U.S. intelligence estimates, but how and when Washington learned about the sale and how it reacted to it can now be learned from largely untapped archival sources. Among the disclosures in today’s publication:

- French restrictions on Israel’s supply of uranium in 1963 made U.S. and British officials suspect that Israel would attempt to acquire yellowcake from other sources without any tangible restrictions to sustain its nuclear weapons program

- A Canadian intelligence report from March 1964 asserted Israel had all of the “prerequisites for commencing a modest nuclear weapons development project.”

- When the Canadians discovered the Argentine-Israeli deal they were initially reluctant to share the intelligence with Washington because the United States had refused to provide them with information on a recent U.S. inspection visit by U.S. scientists to Dimona.

- U.S. and British intelligence were skeptical of the Canadian finding until September 1964 when U.S. Embassy sources in Argentina confirmed the sale to Israel.

- The Israelis evaded answering questions about the transaction. When U.S. scientists visited the Dimona facility in March 1966 as part of the August 1963 secret agreement between Presiden Kenned and PrimeMinister Eshkol, they asked about the yellowcake but their Israeli hosts said that question was for “higher officials.”

- In 1964 U.S. officials tried to persuade the Argentines to apply strong safeguards to future uranium exports but had little traction for securing agreement.

- In 1965, while the CIA and the State Department were investigating the Argentine yellowcake sale, Washington pursued rumors that the French uranium mining company in Gabon had sought permission to sell yellowcake to Israel.

Ever since late 1960, when the CIA learned that the Israelis had been constructing, with French assistance, a major nuclear facility near Dimona in the Negev Desert, the United States and its close allies, Canada and the United Kingdom , and even its Soviet adversary, suspected that Israel had a nuclear weapons program under way.[1] Closely monitoring Israeli nuclear activities Canadian intelligence discovered the yellocake sale sometime in the spring of 1964 and soon shared this sensitive information with the British.

Convinced that the Canadian information confirmed Israel’s interest in nuclear weapons, a British diplomat calculated that the yellowcake would enable the Israelis to use their Dimona nuclear reactor to produce enough plutonium for its first nuclear weapon within 20 months. In light of these concerns, the British shared the information with the U.S. government; both governments were concerned about stability in the Middle East, which the Israeli nuclear program could threaten. Both wanted yellowcake sales safeguarded to curb the Israeli nuclear program and the spread of nuclear weapons capabilities worldwide.

According to the initial Canadian information-as well as additional details later gleaned by the U.S. State Department-in late 1963 Argentina had secretly negotiated a long-term contract with Israel to provide at least 80 tons of yellowcake. While the Americans and the British were initially somewhat skeptical about the accuracy of the Canadian report, subsequent investigations demonstrated that it was correct. Trying to ensure that uranium exports were safeguarded to prevent diversion into military programs, Washington complained to the Argentines about the unsafeguarded sale, then queried the Israelis, and applied intelligence resources to find out more about the transaction.

Washington found that the sale was irreversible and that it could learn nothing about its purpose, although it kept trying. The Argentines said they could only apply strong safeguards to future sales while the Israelis evaded all queries about the yellowcake, although as part of a high-level deal between President Kennedy and Prime Minister Eshkol from 1963 Israel had allowed U.S. government experts to visit their nuclear reactor at Dimona. The U.S. team apparently raised the Argentine yellowcake during a 1966 visit but the Israelis were not helpful in providing explanations. The CIA could not learn anything concrete about the transaction either.

As the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada had routinely acted with the utmost discretion when sharing intelligence information about the Israeli nuclear program, they kept the entire yellowcake sale secret. On this matter there were no leaks; the issue never reached the U.S. media then or later.

Israel’s interest in uranium is as old as the state itself. As early as 1949-50, Israel started with a geological survey of the Negev to determine whether and to what extent uranium could be extracted from the phosphates deposits there. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s Israel explored the viability of the phosphates option, some pilots plants were built, but finally it was determined that it would be too costly. Israel, therefore, had to find uranium from overseas sources.

For the Dimona project the Israelis initially had gotten uranium from France, but in the early 1960s Paris began to restrict the supply and Israel sought to diversify its sources by securing uranium from Argentina, South Africa and elsewhere.[2] Conversely, because the United States was worried about the Israeli nuclear program and its implications for stability in the region, it made efforts to monitor closely Israeli purchases of nuclear material and investigated the Argentine-Israeli deal. While Washington was then exploring ways to establish a global safeguards system to regulate nuclear supplies through the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), nothing yet was available with any teeth, such as the future Nuclear Suppliers Group, to check such sales, much less restrict the Israeli nuclear program.

Early on when American, British, and Canadian intelligence tried to uncover the secrets of the Israeli nuclear program, they clearly understood that Israel needed a reprocessing facility to transform its spent reactor fuel into weapons-grade plutonium. For example, according to an October 1964 National Intelligence Estimate on nuclear proliferation a “major deficiency, in terms of a weapons program, is the lack of a plutonium separation plant.” Although the Israelis had told both the US and Canada that the Dimona facility would include a pilot plant for reprocessing, the widespread assumption was that it was probably too small to produce enough plutonium for a weapons program. That the original French design for Dimona included a large underground reprocessing facility (Machon 2) was one of Israel’s deepest nuclear secrets, which Mordecai Vanunu later revealed.[3] To this day, it is unclear exactly how much Western intelligence knew about the facility and exactly when and how it learned it.

The documents in today’s publication are from the U.S. and the British National Archives. All of the U.S. documents were declassified in the mid-1990s but have lingered in a relatively obscure folder in the State Department’s central foreign policy files at the U.S. National Archives. They may never have been displayed in public before as the file appeared to be previously untouched. A few of the British documents have been cited by other historians, including ourselves, but the fascinating story of British-Canadian-United States intelligence cooperation and coordination has also been buried in relative obscurity. The juxtaposition of U.S. and British records makes a fuller account possible, although some elements of the story remain secret, such as the identity of the Canadian intelligence source on the yellowcake purchase. Only Israeli and Argentine documents, however, can provide the full story of the yellowcake sale.

The documents in today’s publication are from the U.S. and the British National Archives. All of the U.S. documents were declassified in the mid-1990s but have lingered in a relatively obscure folder in the State Department’s central foreign policy files at the U.S. National Archives. They may never have been displayed in public before as the file appeared to be previously untouched. A few of the British documents have been cited by other historians, including ourselves, but the fascinating story of British-Canadian-United States intelligence cooperation and coordination has also been buried in relative obscurity. The juxtaposition of U.S. and British records makes a fuller account possible, although some elements of the story remain secret, such as the identity of the Canadian intelligence source on the yellowcake purchase. Only Israeli and Argentine documents, however, can provide the full story of the yellowcake sale.

Photo: Alan C. Goodison (1906-2006), trained as an Arabist, worked on Israeli nuclear matters at the British Foreign Office’s Eastern Department in the mid-1960s. He coordinated the analysis and distribution of the sensitive Canadian intelligence report on the Argentine yellowcake sale. Goodison is shown in 1983 when he became Ambassador to Ireland (Crown copyright image from collection of Foreign and Commonwealth Office history staff; reproduced under United Kingdom Open License provisions)

THE DOCUMENTS

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office documents in this collection are Crown copyright material and are published with the cooperation of the United Kingdom’s National Archives. To meet the National Archive’s concerns about unauthorized commercial reproduction of copyright material, the British documents are published with watermarks.

A. Overviews and Perspectives

Document 1: Memorandum from Benjamin Read, Executive Secretary, Department of State, for McGeorge Bundy, The White House, “Israel’s Assurances Concerning Use of Atomic Energy,” 18 March 1964, with “Chronology of Israel Assurances of Peaceful Use of Atomic Energy and Related Events,” Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 59, Bureau of Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, Records of Office of Country Director for Israeli and Arab-Israeli Affairs, Records Relating to Near Eastern Arms Initiative, box 1, Talbot in Spring 1964 & Exchange of Letters

This valuable chronology provides a record of the U.S. discovery of the nuclear reactor project at Dimona and the various pledges made by the Israelis, at various levels, in response to requests from the United States,that it was for peaceful uses only. Included in the chronology is an item about a meeting on 25 May 1963 where senior French diplomat Charles Lucet told CIA director John McCone that even though the French had helped build the Dimona reactor, “there might be a nuclear complex not known to the French.” Lucet further stated that the Israelis had tried to purchase “safeguard-free” uranium from Gabon but that the French government stopped the sale through preemptive purchases.

Documents 2 and 3:

2: Department of National Defence, Canada, Defence Research Board, Directorate of Scientific Intelligence, “Possible Israeli Nuclear Military Program,” by J. Koop, DSI Report 1/64, March 1964, Secret, enclosed with letter from A.R.H. Kellas to Allan Goodison, 8 October 1964, Secret

3: Letter from R.C. Treweeks, Defense Intelligence Staff, to Allen Goodison, 8 December 1964, Secret

Source: British National Archives, FO 371/175844

In the late winter of 1964, Jacob Koop, a career intelligence analyst at Canada’s Defence Research Board, prepared a detailed analysis of Dimona’s military potential.[4] Drawing on such intelligence sources as aerial photography, Koop’s basic conclusion was that the reactor had all of the “prerequisites for commencing a modest nuclear weapons development project.” According to Koop, once the Dimona reactor went “critical” it could produce enough plutonium for at least one implosion device by the end of 1965, and an increase in the thermal operating level would make it possible to produce one to two devices annually by 1966. A key question was how the Israelis would reprocess spent fuel into plutonium; Koop cited Israeli-Canadian discussions during Ben-Gurion’s visit in May 1961 when Israeli officials disclosed their intentions to build a “pilot-plant facility” apparently with a capability to produce around 300 grams of plutonium a year. To produce enough material for several weapons a year, however, the Israelis would need a larger reprocessing facility. They would also need a reliable supply of uranium, around 16 to 20 tons per year, to make it possible to change the reactor fuel annually or more often to ensure a steady supply of weapons-grade plutonium.

British officials found Koops’ analysis highly impressive. Arthur Kellas, a British diplomat in Israel, had acquired a copy of the study and in his forwarding letter observed that it was a “model of what these things should be.” Treweeks, with the Defence Intelligence Staff, later commended the Canadian intelligence study, declaring that “we agreed with what is said and with the conclusions.” Apparently the report had not been shared with U.S. intelligence because Treweeks asked that it be treated as “CANADIAN/UK EYES ONLY.”

B. France

Photo: Admiral Oscar A. Quihillalt (b. 1913), chief of the National Atomic Energy Commission, 1955-73, presided over the creation of Argentina’s nuclear establishment. In 1964, he bore the brunt of U.S. State Department inquiries about the yellowcake sale to Israel. This image shows him in 1967 when he was elected Chairman of the Board of Governors of the international Atomic Energy Agency (Image courtesy of Archives, International Atomic Energy Agency).

Document 4: US Embassy in France cable 3199 to Department of State, 8 January 1964, Secret

Source: National Archives Record Group 59, Department of State Records Subject-Numeric File, 1964-1966 (hereinafter SN 64-66 with file name) Inco-Uranium

This telegram, sent through the special “Roger Channel” used for intelligence subjects, refers to an earlier embassy message, number 2319, dated 12 Novembe 1963, which has yet to be found at the U.S. National Archives. That telegram may refer to French actions to halt the supply of uranium to Israel which were alluded to indirectly in this message. Much still needs to be learned about the details, but apparently in the spring of 1963, the French Foreign Ministry cut off the uranium supply to Israel in order to stop the nuclear program. [5] Jacques Martin, a French Foreign Ministry expert on nuclear matters, told U.S. embassy officials that the Israelis, who hadrefused to sign an agreement to purchase uranium exclusively from France, were looking for other sources, most likely Belgium and Argentina. Martin stated that the Dimona reactor could continue operations for only a few weeks without a supply of reactor fuel. It is worth noting that the U .S. government had recently learned that the reactor had just become critical and thus capable of producing plutonium.

Document 5: US Embassy in France cable 4529 to Department of State, 26 March 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

According to another Roger Channel message, the Israeli yellowcake supply problem was continuing, with the Israelis demanding to know why the French were holding up uranium shipments. According to Jacques Martin, the French replied that until Israel was ready to purchase only from France, allowing France “some control over the situation” [in Dimona], the restrictions would continue.

Document 6: Peter Ramsbotham, British Embassy Paris, to William “Willie” Morris, Foreign Office, 11 June 1964, Secret and Guard, with Minutes Attached

Source: FO 371/175844

On 11 June 1964, Peter Ramsbotham, chief of the chancery at the British Embassy in France, met with George Soutou, a senior official at the French Foreign Ministry. Soutou was quite frank about French concerns over Israel, acknowledging that the French believed that the Israelis were, at the least, attempting to “put themselves in a position to make a nuclear bomb, if they wanted to.” According to Soutou, the French-Israeli agreement required the latter to return spent fuel to France, which was keeping “meticulous” records of inputs and outputs. The problem was that the agreement was “loosely drafted” and it did not proscribe the Israelis from using non-French uranium for Dimona, although the French believed that such a proscription was in the agreement’s “spirit.” [6] Therefore, to enforce it, they had already “prevented the sale” of uranium from a former French colony (see Document 1). France would regard any further attempt at uranium purchases a “breach” of the agreement that would lead to the “denial” of further aid. In light of these considerations, Ramsbotham wondered whether the French should be told about the Argentine-Israeli secret deal given their view that any such sale would violate the agreement.

According to the attached minutes, Arkell at the Defense Intelligence Staff was willing to tell the French about the Argentine sale, if the Canadians gave their approval, although it was doubtful whether French denial of further assistance would have any more than a “delaying” impact on the Israeli program. Whether the French were actually told anything is still unclear.

Document 7: US Embassy in France cable 6049 to Department of State, “Franco-Israeli Nuclear Relations,” 11 June 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Apparently, Ramsbotham quickly passed to the Americans information from his talk with Soutou because that same day the U.S. Embassy in Paris provided some highlights of the meeting: the French by then did not want an Israeli weapons capability, but believed that the Israelis were seeking one. We say “by then” because it is clear that at earlier times, when Shimon Peres had negotiated and signed the original nuclear agreement with France in 1957, his French political counterparts, especially Prime Minister Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury, understood the nuclear deal as French assistance for Israel to create its own military deterrent regardless of the formal language, e.g., “peaceful use” reference, in the formal agreements aimed at providing France with political deniability. The uranium that France had supplied, under “loosely worded” safeguards, was formally agreed to be used for peaceful uses. The French had promised to terminate the agreement if they determined that Israel was circumventing it by finding a significant non-French source of supply.[7]

C. Argentina

Document 8: Letter from Alan C. Goodison, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, to A[rthur]R.H. Kellas, British Embassy, Tel Aviv, 29 April 1964, with minutes, Secret and Guard

Source: National Archives (Kew Gardens), FO 371/175843

In a highly classified (“Secret and Guard”) letter to Arthur Kellas, counselor at the British embassy in Tel Aviv, Alan Goodison of the Foreign Office’s Eastern Department disclosed the Argentina-Israel uranium deal. According to unconfirmed intelligence from Canada, Israel and Argentina had “signed an agreement for the sale of the entire Argentine production of uranium concentrate to Israel,” involving the transfer of 80-100 tons over 33 months. “This means that Israel now has virtually unlimited supplies of uranium free of safeguards.” Goodison was aware that the Dimona plant had already reached criticality and he further asserted, referring to recent intelligence (not further identified), that the Israelis already had plutonium reprocessing facilities. Given that, they would have enough plutonium for a weapon within 20 months. While Goodison had no proof that the Israelis planned to build nuclear weapons, “their anxiety to obtain such a large quantity of safe-guard free uranium suggests …sinister motives.”

The British were not aware that the Dimona initial design was based on having a reprocessing plant built underground from the very start, as Vanunu revealed in 1986, but Goodison was making an informed estimate about the trajectory of the Israeli program. He further reported that the Canadians were “reluctant” to provide the information about the Argentine-Israel deal to the Americans because Washington had “refused them information on their recent inspection of Dimona.”

The handwritten comments on the attached minutes are interesting in part because they highlight the extent to which British, like United States, intelligence did not realize how advanced and complete the Israeli commitment to a weapons capability was. According to one comment by one official (whose signature is difficult to read): “At least the Israelis wish to retain the option. At any fork in their nuclear road, when they are confronted with purely civil as against civil plus military paths, they will surely opt for the latter.” Evidently, he did not realize that Israel crossed that fork at the very beginning of its program. Career diplomat David Arthur Steuart Gladstone went further when he commented: “Also this surely throws light on recent Israeli pronouncements on the IAEA and safeguards. This only reinforces my earlier comments on that subject [and?] endorse the last sentence of Mr. Goodison’s letter,” That is, that the “circumstantial” evidence indicating a bomb project was “overwhelming.”

That Argentina had yellowcake to sell to Israel in the first place was the result of a nationalistic nuclear energy policy pursued by Admiral Oscar A. Quihillalt, the director of the National Atomic Energy Commission and an important player in the International Atomic Energy Agency. In 1956 Quihillalt signed a decree turning Argentina’s significant uranium resources into public property with the Commission controlling prospecting, production, and marketing. By the early 1960s, with the assistance of the U.S. Atoms for Peace program, Argentina had two research reactors, and plans for a power reactor.[8] In that context, a yellowcake production capability would be essential to accomplish future plans for reactors.

Document 9: Christopher Audland, British Embassy, Buenos Aires, to Alan Goodison, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, 4 June 1964, with minutes, Secret & Guard

Source: FO 371/175844

Christopher Audland, a political officer at the British embassy, learned from the Canadian chargé that the information on the Argentina-Israel uranium deal “did not originate in Buenos Aires.”[9] The Argentine National Atomic Energy Commission had also sold uranium concentrate to West Germany and made an earlier sale to Israel in 1962 (which the French learned about).[10] According to the minutes, the Canadians had asked the UK’s Defense Intelligence Service to pass the information to the CIA, but skeptical comments by the Agency were creating suspicions that the original report was “threadbare.”

Photo: Walworth Barbour (1908-82) was ambassador to Israel during 1961-73. He presided over the vain effort by U.S. diplomats and CIA officers to learn what Israel had done with the yellowcake. (Image from Still Pictures Branch, National Archives, RG 59-SO).

Document 10: RJ.T. McLaren, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, to British Embassy Bonn, 22 June 1964, Secret

Source: FO 371/175844

In this inquiry about West German purchases of unsafeguarded uranium from Argentina and a possible re-export to Israel, McLaren confirmed that the information about the Argentine-Israeli deal had been “passed to the Americans,” with Canada’s permission. Moreover, the U.S. State Department was also to be informed by Patrick Wright, with the British Embassy in Washington. The subject and the degree of Israeli-West German nuclear cooperation has been for years a matter of speculation, but firm factual knowledge about it is unavailable.

Document 11: Alan C. Goodison, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, to C. J. Audland, British Embassy, Buenos Aires, 22 June 1964, Secret

Source: FO 371/175844

Noting some inaccuracy in the Canadian report–Argentina could not have offered to sell its “entire production” of uranium if it was also selling concentrate to Germany and trying to sell it to Japan—Goodison asked Audland to “keep your ears to the ground” to find the “exact quantities” involved.

Document 12: D. Arkell, Defense Intelligence Staff, to R. J. T. McClaren, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, 1 July 1964

Source: FO 371/175844

While the British learned about 25 June that U.S. intelligence had information confirming the Canadian report, it must have been a shaky source. According to this letter from an official at the recently created Defense Intelligence Staff, [11] a skeptical reaction from Washington about the intelligence on the Argentine-Israeli sale led the Canadians-“our previous informants”-to “take a second look at the sources of the report.” Canadian intelligence was “now very doubtful about [its] reliability.” In handwriting, Arkell observed that this development “disposes” of the proposal to use the information to encourage the French to break off a supply relationship with the Israeli nuclear project.

Document 13:AR.H. Kellas, British Embassy, Tel Aiv, to Alan C. Goodison, 6 July 1964, Secret, excised copy

Source: FO 371/175844

Kellas in Tel Aviv was curious but somewhat skeptical of the claim in Goodison’s 29 April letter that the Israelis might have “facilities for plutonium separation.” The Embassy had “not seen such evidence and should be grateful to know what it is.” Whether Goodison wrote back about the evidence that he had mentioned in his 29 April letter is not clear. The existence of a plutonium separation facility was probably the crown jewel among Israel’s nuclear secrets, one that the U.S. inspectors did not uncover during all of their visits to Dimona through 1969.

Document 14: Department of State Airgram CA-528 to US Embassies in Israel and Argentina, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 15 July 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

With the doubts about the Canadian report, the U.S. government decided to look into it. This joint CIA-State Department message reported “unconfirmed” intelligence of an Argentina-Israel deal struck on 3 November 1963. According to the reports, Argentina would sell the entirety of its uranium concentrate supply to Israel for three years without safeguards. The Department of State instructed the embassies to mount an intelligence collection effort to provide, by 1 September, specifics on the arrangement: the amount to be sold, cost, schedule, and any safeguards attached.

Unlike the British communications, which were signed by individual officials, the U.S. documents published here were organizational products, generally signed by ambassadors or the secretary of state. Prepared in a variety of offices at the State Department, some were drafted by officials from more than one government agency.

Document 15: Alan C. Goodison, Eastern Department, to C. J. Audland, British Embassy Buenos Aires, 21 August 1964, Secret

Source: FO 371/175844

Goodison reported that U.S. officials have had a “skeptical reaction” to the Canadian report because they had no information about an Argentine-Israeli deal and the Argentines had not reported exports to Israel in their Official Bulletin. If correctly reported, this was a surprisingly narrow and naive response.

Document 16: R.C. Treweeks, Defense Intelligence Staff, to Alan C. Goodison, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, 26 August 1964, Secret Guard

Source: FO 371/175844

The Defense Intelligence Staff had no information to support the Canadian report, although the Israelis may have had “exploratory conversations” on a uranium deal with Argentina. Moreover, “little evidence” supported the argument that the Israelis had a chemical separation plant at Dimona. As the world learned from whistle blower Mordechai Vanunu in 1986, a building near the reactor designated by the Israelis as a “laundry” masked an underground separation facility with six separate floors. This was part of the original French plan. It appears that none of the seven or so U.S. inspection teams that visited Dimona in the period 1961-69 had ever positively detected that underground facility It is still a puzzle whether and when U.S. intelligence, especially the CIA, became aware of the reprocessing facility and, if it did, whether any information was shared with the AEC-led inspection teams. John Hadden, the CIA station chief, was instructed not to have any contact with, let alone brief, the inspection teams.[12]

Document 17: US Embassy in Argentina airgram A-230 to Department of State, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 2 September 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Whether the U.S. Embassy in Israel replied in time to meet the 1 September deadline assigned by the State Department in its 15 July directive is not clear (perhaps it was sent through CIA channels). Just past the deadline, however, the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires produced an “interim report” confirming the sale of Argentine uranium to Israel. The Argentines had authorized a total of 100 tons of “yellow cake,” at a minimum price of $15/kilogram, for sale to Israel. Sale contracts were permitted over a three-year period, beginning 1 January 1963 and shipments could be extended nine months from the end of that period. Proceeds of sales were to be used to purchase machinery and equipment for use in the atomic sector. According to a government decree, the uranium was to be used solely for the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Document 18: D. Arkell, Defense Intelligence Staff, to Alan C. Goodison, Eastern Department, Foreign Office, 6 October 1964, Secret

Source: FO 371/175844

With the State Department receiving confirmation of the sale, U.S. intelligence was no longer skeptical about the Canadian report. According to a U.S. report which was made available to British intelligence, which in turn disseminated it to the Foreign Office, “an agreement was concluded between Argentina and Israel for the sale of at least 80 tons of U3O8.” Moreover, “recent … uranium exports had gone only to Israel.” The amount involved “is far in excess of that needed … to operate the Dimona reactor only for research purposes.” The Cordoba plant is “reported to be producing concentrate at the current rate of about 60 tons per year” and by 1966 Argentina should have no trouble “meeting contracts up to 100 tons of yellowcake.” Arkell agreed with the assessments but wanted to know how much uranium had actually been shipped.

Document 19: Department of State airgram CA-3992 to US Embassy in Argentina, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 9 October 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Responding to the Embassy’s report, the State Department asked it to obtain as much information as possible on the end-use of uranium sold to Israel, and in particular on the issue of safeguards. If Argentina was not requiring safeguards on uranium exports, the Department instructed the Embassy to approach Argentine officials as soon as possible and present them with an aide-memoire discussing the importance of safeguards. The results of the approach should be reported to a Working Group to Review the IAEA Safeguards System. Working within the IAEA, the U.S. government had been trying to establish a “common front” in support of the application of safeguards on the “transfer of significant quantities of nuclear materials.” [13] Therefore, the Department asked the Embassy to convey to the Argentines that a sale made without safeguards “would represent a most serious breach in the efforts the U.S. and other western suppliers have made over the last ten years” to assure that “atomic assistance” is “appropriately safeguarded.” Also sent was an explanation of the technical basis for IAEA safeguards on natural uranium.

Document 20: US Embassy in Argentina cable 555 to Department of State, 19 October, 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Meeting with embassy officials, the chief of the National Atomic Energy Commission Admiral, Oscar A. Quihillalt, informed them that Argentine uranium sales agreements with Israel, or with any other country, had only general safeguard provisions stipulating that the uranium would be used peacefully. Argentina did not require reports, inspections, or any other independent verification that were loosely equivalent to Article XIII of the IAEA statute. Quihillalt observed that safeguards on natural uranium were impractical, and that other countries sold without safeguards. He had no definitive information on Israeli plans for use of the uranium.

Document 21: US Embassy in Argentina cable 578 to Department of State, 23 October, 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

During a meeting with Foreign Office officials, a U.S. embassy officer left a copy of the aide-memoire and the note on safeguards. Emphasizing that the U.S. did not object to the sale as such and was not suggesting that Israel intended to use uranium for non-peaceful purposes, the officer stated that the U.S. sought cooperation because of the principle that significant nuclear assistance should only be provided in accordance with appropriate safeguards. The Argentine diplomat refrained from comment because it was necessary to discuss the matter with the Argentine Atomic Energy Commission.

Document 22: US Embassy in Argentina cable 591 to Department of State, 27 October 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

During a discussion with Admiral Quihillalt and CNEA, Embassy officials provided the aide-memoire and the paper on IAEA safeguards. The Admiral was more receptive to the U.S. position than previously (he would later urge Argentina’s adherence to the NPT[14]) and was glad to know that Washington was not in touch with the Israelis about the sale.

Document 23: Department of State cable 549 to US Embassy in Argentina, 25 November 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Expressing concern over the lack of a response to U.S. questions on the reported uranium sale to Israel, the Department asked the Embassy to relay concern to the Foreign Office. The State Department, ACDA, and the AEC were considering more “representations” to Argentina and possibly to Israel if the Argentines did not respond. If possible, Embassy should indicate U.S. government “apprehension” over nuclear proliferation and sales of unsafeguarded uranium.

Document 24: US Embassy in Argentina cable 749 to Department of State, “Sale of Uranium to Israel,” 30 November 1964, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The Embassy had delivered a note urging a quick response to the U.S. aide-memoire on safeguards; while the Argentines had not replied, the Foreign Office appeared to support safeguards, because of the proliferation risk and also domestic political interests. Moreover, requiring safeguards would establish that Argentina was a seller of nuclear materials for peaceful uses only. Even if the Foreign Office view did not reflect overall government thinking, the Embassy believed that an internal Argentina dialogue should take place before Washington made further representations. The sale was not yet public knowledge in Argentina.

Document 25: Alan Goodison to R.Treweek, Defence Intelligence Staff, 22 December 1964, Secret

Source: FO 371/175844

The Defense Intelligence Staff’s positive evaluation of the Canadian intelligence analysis (see Document 3) prompted Goodison to write to Kellas in Tel Aviv about it. Goodison further noted that the “reservations” (hesitations?) that the Foreign Office had about a possible date for an Israeli nuclear bomb were “no longer valid and that we must accept the end of 1968 [sic] as the earliest possible date.” As the Canadian report suggested an Israeli test by 1966, either 1968 was a typo or the Defence Intelligence Staff provided more detailed comments than are available in the file.

Document 26: Department of State cable 729 to US Embassy in Argentina, 2 February 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Months later, the State Department asked the Embassy to remind the Argentine government that it was awaiting a response to the U.S. aide-memoire on the uranium sale to Israel. The Department also asked the Embassy to review the “full extent” of Argentine exports of uranium so that the U.S. government had the opportunity to discuss any future transactions in advance.

Document 27: US Embassy in Argentina airgram A-691 to Department of State, “Argentine Sale of Uranium Oxide to Israel,” 3 February 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The Embassy had gotten the Argentine reply ten days earlier so the State Department message the day before served as a reminder to translate the reply and send it on. During a meeting, Admiral Quihillalt observed that the deal with Israel had been concluded before the IAEA had finalized protocols for safeguards measures; therefore, Argentina did not feel it practicable to include reporting and inspection requirements. Nevertheless, he indicated that safeguards equivalent to those of the IAEA’s would be placed on future sales. The Admiral also observed that without a “general agreement between Western governments” on the application of safeguards to sales of fissile material, bilateral agreements between a few governments would not have much of an impact. Noting that the official Argentine response did not include an assurance about future exports, the Embassy observed that it would not follow up that problem without instructions from the Department.

Document 28: Department of State airgram A-163 to US Embassy in Argentina, “Argentine Sale of Uranium Oxide to Israel,” 27 April 27 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Responding to a request for instructions, the Department informed the Embassy that Washington had begun approaching other governments to establish a common policy on the mandatory application of IAEA safeguards to materials and equipment supplied to other countries. An approach to Argentina was to come in the future, when the IAEA was closer to an agreement. In the meantime, the Argentines should be requested to apply safeguards to future sales and if a deal with Israel was renegotiated the government should consider applying safeguards to uranium exports to that country.

Document 29: Department of State cable 7659 to U.S. Embassy in the United Kingdom, 3 June 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

This cable reports on a conversation between a British Embassy officer and one or two State Department officials. The Embassy officer reported that Israel’s purchases of uranium added up to 190 tons—more than what was needed for research. They recalled statements by Israeli Prime Minister Eshkol that Israel would not be the first country to introduce an atomic weapon to the Near East, but that it must retain the capability. The Embassy officer proposed a joint U.S.-British approach to Argentina on safeguards; the State Department official replied that such approaches had not been successful but he would be in touch with the British on this problem.

Document 30: US Embassy in Argentina airgram A-160 to Department of State, “EXCON: Argentine Exports of Uranium Oxide,” 21 August 1965, Confidential

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

A request by an Argentine Congressman gave the yellowcake sale to Israel a public airing, but the publicity did not get reported internationally. The Congressman asked the government questions, including how much uranium had been exported and whether Argentina had sold uranium to other countries. The Embassy planned to watch the results of the inquiry closely to get details on the specifics of the deal. Unlike a U.S.-Argentina controversy in 1963 over oil company contracts, which became highly public on both sides, the yellow-cake transaction was unreported abroad.[15]

Document 31: Department of State airgram CA-2198 to US Embassies in Argentina and Israel, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 24 August 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Owing to discrepancies in the available data, the State Department requested, on an “alert basis,” several pieces of information: the total amount to be shipped under the 1963 contract, how much uranium had been shipped to Israel already, any information on a new agreement between the two countries, what safeguard controls did Argentina have in place, and the current status of operations at Argentine uranium processing plants. Citing a variety of diplomatic and intelligence reports from the previous year, the Department pointed out variations in the data on quantities shipped and terms of a new contract, among other issues.

Document 32: US Embassy in Israel airgram A-350 to Department of State, “Argentine Uranium,” 22 October 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The Embassy in Israel reported that it had no information on Israeli uranium imports. Suggesting that the only way to obtain information was through a high-level inquiry to the Israeli Foreign Ministry, the Embassy requested specific instructions if the Department of State agreed. Signed by Embassy science officer Ralph Webber, the message received clearances from Ambassador Walworth Barbour, the military attachés, who reported to the Defense Intelligence Agency, and CIA station chief John L. Hadden.

Document 33: US Embassy in Argentina airgram 763 to Department of State, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 10 April 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Responding to questions in the Department’s August 1965 airgram, AEC representative Lester Rogers reported that the Embassy had no new information. As reported previously, language about safeguards in Argentina’s uranium sales agreements with Israel was very general. A table included data on annual production of uranium during 1958-1965, including dry tons of ore (U3O8/triuranium octoxide). Also provided was information on production capacities of the uranium processing plants at Cordoba and Malargue. A new facility planned for Cordoba would produce nuclear grade UO 2, used for reactor fuel rods, at 100 tons annually.

Document 34: Department of State cable 1250 to US Embassies in Argentina and Israel, “Israeli Purchase Argentine Uranium,” 11 May 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

After making inquiries, the Department was unable to determine the location of the uranium sold to Israel by Argentina, but learned that it was in excess of Israeli requirements for peaceful use. A failure by the Israeli government to announce intended use could have an adverse effect on the political situation in region. Therefore, the Department would inquire at a high level about the location of the uranium. The Embassy in Argentina could inform the government if necessary, while the Embassy in Israel should await instructions.

Document 35: US Embassy in Argentina cable 1776 to Department of State, “Israeli Purchase of Argentine Uranium,” 26 May 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The Embassy did not believe it was advisable to inform the Argentine government of U.S. plans to ask the Israeli government about the location of the uranium.

Document 36: Department of State cable 1052 to US Embassy in Israel, 2 June 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The State Department directed Ambassador Barbour to advise the Israeli government that the Department was “generally satisfied” by the inspection of the Dimona plant. Barbour was further instructed to express concern over the lack of information supplied by technical personnel—implying these questions were posed to the Israelis during the U.S. inspection visit at Dimona—about the purchase and the location of the uranium ore from Argentina and to express hope that Israel would clarify the situation. According to the cable, in February 1966 Secretary Rusk had observed to Foreign Minister Eban that Israel apparently was following a policy aimed at creating “[nuclear] ambiguity” in the region, but in fact it created a great deal of “ambiguity” (uncertainty) in Washington about Israel’s nuclear intentions and its pledges for peaceful use. What Rusk meant was that that ambiguity undermined and eroded confidence in the pledges to the United States. Indeed, Rusk believed that Israel was playing dangerous games with its posture of nuclear ambiguity, signaling different messages to different players. Therefore as long as the Israelis were creating “apprehension” in Washington by not providing answers to questions about yellowcake, they should expect the U.S. to be “extremely clear and utterly harsh on non-proliferation.”

Document 37: US Embassy in Israel cable 1333 to Department of State, 15 June 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Ambassador Barbour spoke with Foreign Minister Abba Eban along the lines of Department telegram 1052 [Document 36] and further asked about the location of the Argentine uranium concentrates. Eban remained noncommital and merely said he would inquire further among those who know (leaving the impression that as Israel’s foreign minister he knew little about atomic matters). This telegram is a bit cryptic because it refers to some unknown “attitude” issue on the part of Dimona director Yossef Tulipman and other managers [“technicians”] during the most recent Dimona visit by U.S. scientists. One may speculate that the attitude problem emerged when the Dimona managers were asked about the yellow cake and apparently refused to shed light on the matter. According to Israeli Foreign Ministry official Moshe Bitan, who served as a liaison with the American scientists, it was possible that the “technicians” were “unaware” of “such arrangements” because the information was for “higher officials” only. That Tulipman would not have full knowledge about an important supply of uranium to Israel is unlikely but Bitan had no incentive to clarify the situation to U.S. diplomats. Barbour further advised Eban that he would revisit safeguards in the future.

Document 38: US Embassy in Israel cable 7 to Department of State, 1 July 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Barbour raised the Argentine uranium matter with Eban who said he would confer with Deputy Minister of Defense Zvi Dinstein “who keeps the store” [meaning: Dinstein now was Dimona’ new political boss]. Eban said he would provide more information soon, but if he did so it has not yet surfaced in the archival record.

D. Gabon

Document 39: Department of State cable 131 to US Embassy in Gabon, 23 March 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

While the State Department was making inquiries about the Argentine sale, it also pursued recent intelligence that the Compagnie des Mines d’Uranium de Franceville, the French mining company operating in Gabon, had requested permission to ship uranium ore to Israel.[16] The source of the intelligence was not mentioned; it is not known, for example, whether the Israelis had approached company managers or officials in the Gabonese government. But knowing that a similar incident had occurred in 1963 (see Document 1), the Department wanted to explore the issue and asked the Embassy for comment and related information.

Document 40: US Embassy in Gabon cable 364 to Department of State, 8 June 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Belatedly responding to the Department’s query, the Embassy observed that uranium was a “most sensitive” matter in Gabon. Besides President Léon M’ba, only the Minister of the National Economy and Mines and his predecessor would know of any diversion and no information had come from those sources.Officials with the Compagnie de Franceville and French mining advisors, normally cooperative and helpful, were “evasive” and sometimes “hostile” when asked about uranium shipments to Israel. One official cited the difference in French and American nuclear policies, saying that no French official would divulge the information that the State Department sought. More information could come by formally raising the issue with the President of Gabon or the Foreign Minister.

Document 41: US Embassy in France cable 786 to Department of State, 11 August 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

Commenting on the Embassy’s report, the U.S. Embassy in France observed that the French controlled production and export of Gabonese uranium, with about 440 tons of uranium metal produced annually. Therefore, any diversions would occur under French and not Gabonese authority. The Embassy deferred to its U.S. counterparts in Gabon on Gabonese ability to secretly divert uranium ore without French permission. That, however, was “unlikely” in view of France’s success in 1963 to thwart a diversion.

Document 42: US Embassy in Gabon cable 157 to Department of State, 10 November 1965, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

During a recent visit to the Nounona uranium mines, Ambassador Bane learned that the entire production of processed ore went to France for metal extraction by the government’s Atomic Energy Agency. Given total control, if the French wished to supply uranium to Israel, it could do so without disclosure to the Gabonese government.

Document 43: US Embassy in Gabon airgram A-49 to Department of State, “Reported Diversion of Gabonese Uranium to Israel,” 11 November 1966, Secret

Source: SN 64-66 Inco Uranium

The embassy reported that the Gabonese Government had recently asserted that France was the sole procurer of its uranium and that the uranium did not cover France’s consumption needs, thereby excluding the possibility that Gabonese uranium could be resold to a third country. An Embassy comment stated that this did not exclude the possibility of diversion to Israel, but the Gabonese statement was consistent with the Embassy’s November 1965 message.

NOTES

[1] For background on Israeli nuclear history, see Avner Cohen, Israel and the Bomb (New York, 1998) andThe Worst-Kept Secret: Israel’s Bargain with the Bomb (New York, 2010). See also the documents in the “Israel and the Bomb” collection on the National Security Archive site.

[2] U.S. documents on the Israel-South African yellowcake connection have yet to surface, but Sasha Polakow-Suransky’s important book , The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa (New York, 2010) is invaluable on this and other matters; see 42-43.

[3] For a full account of the Vanunu revelations, see Frank Barnaby, The Invisible Bomb: The Nuclear Arms Race in the Middle East (London, 1989).

[4] Koop’s analysis, found in British records, has been previously discussed by Zachariah Kay in The Diplomacy of Impartiality: Canada and Israel, 1958-1968 (Waterloo, 2010), 41-42.

[6] Foreign Minister Couve de Murville had already acknowledged to President Kennedy that this was a problem. See Bar-Zohar, Shimon Peres, at 249.

[8] Emanuel Adler, The Power of Ideology: The Quest for Technological Autonomy in Argentina and Brazil(Berkeley, 1987), 290-291. Typically, the Argentine military ran nationally-important industrial research and development organizations. See also Jacques E. C. Hymans, The Psychology of Nuclear Proliferation: Identity, Emotions, and Foreign Policy (New York, 2006), 144.

[9] Audland wrote an interesting memoir, including a chapter on his diplomatic experience in Argentina, but it did not touch on the yellowcake episode. See Christopher Audland, Right Place – Right Time (Stanhope, 2004), 140-68.

[11] See Peter Davies, “Estimating Soviet Power: The Creation of Britain’s Defence Intelligence Staff, 1961-1965,” Intelligence and National Security 26 (2012): 818-841.

[13] See Astrid Forland, “Coercion or Persuasion? The Bumpy Road to Multilateralization of Nuclear Safeguards,” The Nonproliferation Review 16 (2009): 47-64, for a detailed account.

[15] Dustin Walcher, “Petroleum Pitfalls: The United States, Argentine Nationalism, and the 1963 Oil Crisis,”Diplomatic History 27 (2013): 24-57.

[16] For background on French uranium mining activities in Gabon and French-Gabonese relations,see Gabrielle Hecht, Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Nuclear Trade (Cambridge, 2012).