Iran 1953: The Role of MI6, British Petroleum and Kermit Roosevelt’s Countercoup

Kermit Roosevelt, one of the leading figures in the CIA- and MI6-backed coup against Mohammad Mosaddeq in 1953.

As the Iranian revolution crested in 1978-1979, the CIA approved a memoir by Kermit Roosevelt, one of the architects of the 1953 coup against Iran’s nationalist prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq. After first balking at the potential exposure of numerous “secrets,” the CIA relented when Roosevelt agreed to delete all mention of MI6 and made over 150 other changes that rendered the book “essentially a work of fiction,” according to recently declassified CIA files posted today by the National Security Archive.

The internal CIA deliberations over Roosevelt’s Countercoup: The Struggle for the Control of Iran (McGraw-Hill, 1979 [sic]) were released through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and provided to the National Security Archive by the original requester, researcher Faisal A. Qureshi. They are posted here for the first time.

Missing from the documents is what happened when British Petroleum discovered thatCountercoup (falsely) identified its predecessor, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), as the instigator of the operation. In fact, MI6 originated the plan. The oil concern threatened to file suit, which prompted publisher McGraw-Hill to pull virtually the entire print run of 7,500 copies in 1979. 400 copies had already made it out to reviewers and bookstores, but most of those were returned.[1]

In a final twist, the revised version of the book hit the streets in August 1980 (retaining the 1979 date on the copyright page), but with the reinsertion of numerous references to “British intelligence” as the key player on the British side (replacing “AIOC”), even though disguising MI6’s role had been one of the principal reasons for censoring the volume in the first place.[2] No official explanation has ever surfaced for this decision, which has directly undermined continuing claims by both U.S. and British intelligence that any acknowledgement of London’s part in planning the coup would present a grave threat to the national security.

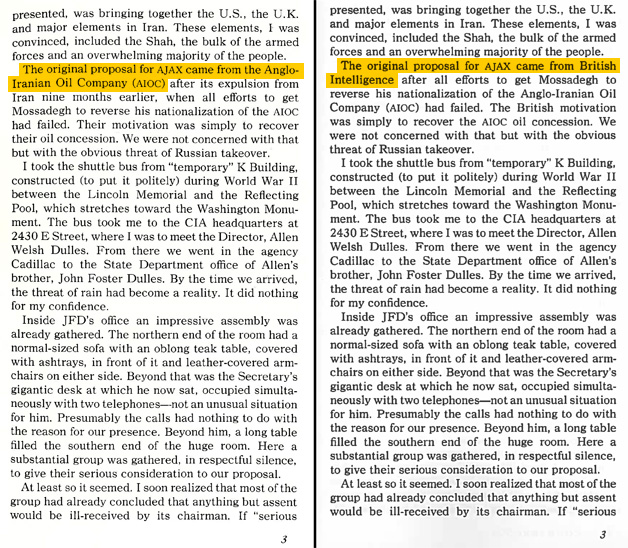

Tampering with history: Two versions of page 3 from Countercoup show how the author and publisher, with CIA approval, changed the initiator of the coup idea from the “Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC)” in the original version (left) to “British Intelligence” in the final edition (right). (Special thanks to Jain Fletcher, Library Special Collections, Young Research Library, UCLA — and particularly to the unnamed UCLA librarian who presciently preserved a copy of the original edition from pulping in 1979.)

The back story to the publication of Countercoup has long been a puzzling subplot to the troubled historiography of the 1953 events in Iran. How could the CIA permit a former operative to publish a 217-page personal account about a major covert operation, yet for decades rebuff virtually every public request to declassify the underlying documentation? One of those requests led to a National Security Archive FOIA lawsuit in the late 1990s. The Archive sought the release of a well-known CIA internal history of the operation but obtained only a single sentence out of the 200-page document. The New York Times, which obtained a leaked version of the classified history, subsequently published it on its Web site in April 2000.

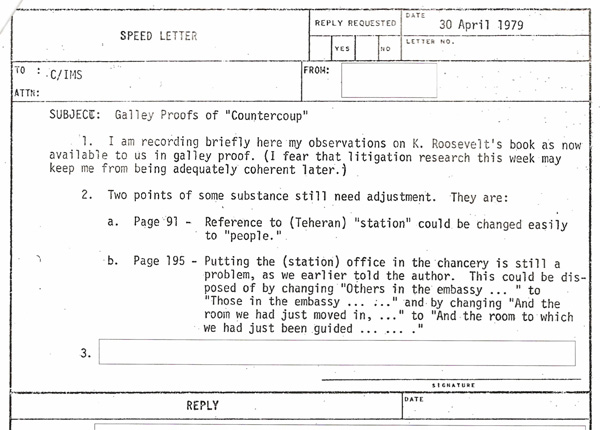

This CIA Speed Letter from April 30, 1979, indicates two final changes the CIA wanted Roosevelt to make, on pages 91 and 195 (see following images). Presumably the 150+ other required changes were more substantive and consequential.

The Countercoup story is also relevant in light of the long-delayed publication of the State Department’s retrospective Foreign Relations of the United States volume on the coup. In limbo since first entering the declassification gauntlet in 2006, the volume is expected to be released finally in Summer 2014.

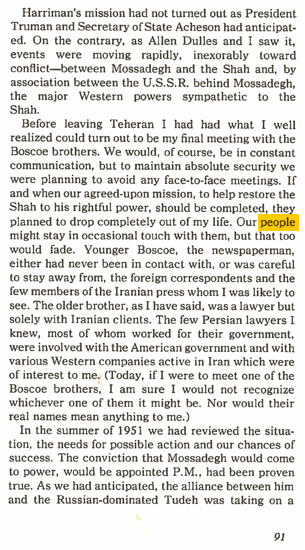

At CIA insistence, the reprinted version of Countercoupdutifully substituted the word “people” for “station” on page 91 (see April 30, 1979, Speed Letter).

Finally, the Countercoup experience offers insights into the larger questions of how the CIA decides what it will allow to be made public, by whom, and with what implications for our understanding of the past.

Running through several of the documents posted today is the theme of preferred treatment for favored individuals on the matter of what they are authorized to publish. Prior to the early 1970s, senior officials who wanted to write about intelligence activities or their own experiences typically met little resistance, if not outright encouragement.

That changed substantially with United States v. Marchetti, a 1972 court case involving former CIA operative Victor Marchetti who, with ex-State Department official John Marks, eventually published a groundbreaking, but censored, exposé of the agency, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (Alfred A. Knopf, 1974). After the courts in the case mainly sided with the intelligence community, the CIA instituted a formal mechanism for clearing works by current and prior officials, the early experience with which is reflected in today’s posting.[3] Still, Roosevelt had certain expectations about his freedom to write about his clandestine exploits and he enjoyed a level of responsiveness from former agency colleagues that would be unimaginable to the average FOIA requester.

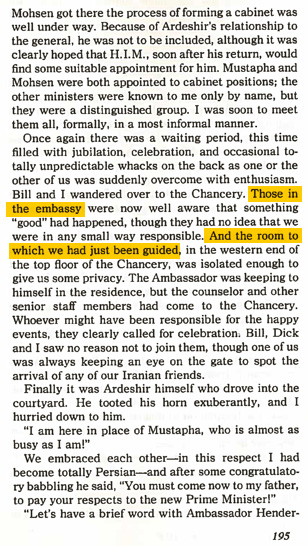

Page 195 of the new version of Countercoupincorporated this highlighted change, per the April 30, 1979, Speed Letter (above).

While Roosevelt’s case has to do with former agents, at other times the CIA engages with outsiders — i.e. striking deals over special access to classified material — in ways that are manifestly self-serving and cast serious doubt on assertions about what secrets require protection. Those deals might involve granting a journalist direct access to internal agency operational histories, or allowing someone with a security clearance to take extensive notes from classified records then clearing those notes for the exclusive use of a particular author.

The best-known instance of the former kind of deal was Evan Thomas’s The Very Best Men: Four Who Dared: The Early Years of the CIA (Simon & Schuster, 1996). A prominent case of the latter agreement was Benjamin Weiser’s A Secret Life: The Polish Officer, His Covert Mission, and the Price He Paid to Save His Country (PublicAffairs, 2004), about ex-informant Ryszard Kukliński.

Both Thomas and Weiser have candidly explained their decisions to enter into these special understandings, and their works have earned critical praise and added substantially to public knowledge. But other researchers have systematically been denied access to the same materials through standard declassification avenues like the FOIA. In the Weiser case, the agency has denied access to the notes he used not on national security grounds, since they were declassified for his use, but for ostensibly commercial reasons, using the (b)(4) exemption to FOIA.

The CIA’s granting of exclusive entrée to restricted information increases public uncertainty over the degree to which official control is coloring the telling of history. The less transparent government declassification policies are, and the more it appears their main purpose is simply to boost agency interests, the more likely will be outbreaks like the leaking of the Pentagon Papers, the CIA’s history of the 1953 coup, and the many revelations of Manning, Snowden, and Assange.

Cover page of the CIA’s earliest internal history of the 1953 coup, authored by operation planner Donald Wilber in 1954. This secret account was presumably the one Roosevelt requested special access to as he prepared to write Countercoup. The CIA Inspector General advised him to file a FOIA for it. (Read the document here)

DOCUMENTS

Document 1: CIA, “Secrecy Agreement,” signed by Kermit Roosevelt, April 6, 1949, Restricted

By signing this secrecy agreement, Kermit Roosevelt agreed to abide by the provisions of the Espionage Act of 1917 pertaining to disclosure of defense-related information, and acknowledged the penalties for violating the act. He agreed never to “divulge, publish nor reveal” classified information “except in the performance of my official duties” unless specifically authorized, and recognized the obligation was binding even after leaving government duty.

Document 2: Memorandum for General Counsel, from John H. Waller, “Agency Review of Proposed Unofficial Publications by Former Employees,” January 11, 1977, Confidential

In this memorandum, CIA Inspector General John Waller recounts for the agency’s General Counsel his awareness of and involvement with Roosevelt’s plans for a book on the coup. (Since leaving the intelligence world in the late 1950s, Roosevelt had become a consultant specializing in the Middle East, and maintained lucrative ties to the Shah, lobbying for him and encouraging him to buy U.S. military equipment from other Roosevelt clients.[4]) Waller says he told Roosevelt early on that in addition to inspecting his manuscript, the CIA “would probably also be interested in whether or not the Shah of Iran would take umbrage at such a book.” Roosevelt responded that, “to the contrary,” he had discussed it with the Shah personally and was certain he “would in fact welcome” it.

Waller reveals that CIA Director George H. W. Bush spoke to Roosevelt directly about the project the previous June, then contacted Waller “to see what I could do to be of assistance.”

The timing of this memo, more than half a year later, follows promulgation of a new proposed agency regulation on clearances for former officials’ publications. Waller goes through his prior interactions with Roosevelt on the subject, invoking the Marchetti decision. He seems intent on making clear that even though he and Roosevelt see each other “socially on occasion” and Waller himself was a key player in the 1953 operation (not detailed in the memo), he has not extended his former colleague any special favors. For instance, when Roosevelt asked for access to the agency’s internal history of TPAJAX (the code word for the coup), Waller told him “he was at liberty to apply for it under the Freedom of Information Act.”

Document 3: Memorandum for the Record from the Office of General Counsel, “[Excised] Agency Review of Proposed Unofficial Publications by Former Employees,” January 13, 1977, Non-classified

Here, an attorney from the Office of General Counsel memorializes developments relating to the CIA’s evolving policies for dealing with pre-reviews of “unofficial publications,” i.e. including those prepared by former officials. He notes some of the impact of theMarchetti decision on how the agency may or may not restrict such publications.

Document 4: Memorandum for General Counsel from John H. Waller, “Publication by Former CIA Official,” January 19, 1977, Non-classified

Waller reports that Reader’s Digest Press plans to publish Roosevelt’s book. He says that in talking to Roosevelt he “stressed” the “important role” of the OGC in clearing manuscripts, to which Roosevelt replied that “he felt he had done what was proper to have informed Mr. Bush of his intentions early on.” But Roosevelt added he would be willing to speak to an OGC representative. Waller “again reminded him that among other things he would have to be careful about” a particular topic, but the details are excised in the memorandum.

Document 5: Memorandum for Director of Security (Attn: Chief, EAB/OS), from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt Book on Iran,” February 2, 1977, Non-classified

A CIA associate general counsel (AGC) reports on a meeting with Roosevelt, held at Waller’s suggestion to drive home the “ramifications of the secrecy agreement” for books by former agency officials. The AGC provided Roosevelt a copy of his 1949 agreement (Document 1). Roosevelt in turn handed over four chapters of the manuscript that corresponded to his tenure at CIA. By this time Roosevelt has signed a contract with Reader’s Digest Press. He asks that a review be completed before he is due to travel to Iran later in the month to see the Shah.

Document 6: Memorandum for Chairman, Publications Review Board, from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Meeting with Mr. Kermit Roosevelt,” February 24, 1977, Non-classified

At Roosevelt’s request (Document 5), the Publications Review Board (PRB) performed a speedy review of his partial manuscript. The PRB’s members had a number of reactions, which the OGC conveyed to Roosevelt, who was said to be “most willing to cooperate.” Roosevelt reported that Reader’s Digest Press had since gone out of business and his trip to Iran had been delayed. Most of the rest of the memo, presumably detailing the PRB’s comments, is excised.

Document 7: CIA Routing and Record Sheet for Members of the PRB, from Executive Secretary , Publications Review Board, “Kermit Roosevelt – 28 Morad [sic]: The Countercoup,” June 30, 1978, Secret

This routing sheet indicates that the PRB has received 11 chapters of Roosevelt’s manuscript, which the Board is given three weeks to review so that Roosevelt can submit them to his new publisher on August 1. (McGraw-Hill eventually picked up the contract from the defunct Reader’s Digest Press.) The book’s tentative title, 28 Mordad: The Countercoup, refers to the date on the Persian calendar (August 19 on the Gregorian calendar) when Mosaddeq was finally toppled.

Document 8: CIA Routing and Record Sheet for Chairman, Publications Review Board, from Chief, DO/IMS, (no subject), July 10, 1978, Confidential; with attached Speed Letter to C/IMS, from [Name Excised], “Second Draft of ’28 Mordad: The Countercoup’ by Kermit Roosevelt,” July 7, 1978, Internal Use Only

The chief of the CIA’s Information Management Staff (C/IMS) (William F. Donnelly — see Document 9) notifies the PRB chairman that his staff is having “considerable difficulty” with the manuscript. A “speed letter” from an internal reviewer suggests offering a “counter-proposal” to Roosevelt — to publish the book in a special, classified edition of the in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence, and to give Roosevelt access to internal (Top Secret) records for the purpose. The reviewer hopes the former operative will see the value of helping the “upcoming generation of Agency personnel” by giving his personal account of the “first U.S.-sponsored subversion of a government outside the Soviet orbit.” The reviewer mentions the still-classified record is about to be turned over to State Department historians – that is, for possible use in its FRUS series. (When the relevant volume eventually appeared in 1989, it came under intense public criticism for omitting all references to U.S. or British participation in the 1953 coup.)

Document 9: Memorandum for Executive Secretary, Publications Review Board, from William F. Donnelly, “Mr. Kermit Roosevelt’s Draft: 28 Mordad: The Countercoup,” July 17, 1978, Confidential

As promised in his July 10 note (Document 8), the chief of the CIA’s Information Management Staff forwards his office’s objections to Roosevelt’s text. It labels a number of specific items as “Unacceptable.” Unfortunately, all of them have been excised (four numbered paragraphs totaling over one-and-a-half pages) in this version of the document. Donnelly disparages the OGC’s previous “cordial discussion” with Roosevelt as obviously ineffectual. While “that method of conveying Agency views to potential authors is satisfactory in most instances,” he advises an “operationally oriented review of this Directorate’s objections with Mr. Roosevelt” and offers to “discuss alternatives with the Board.” Clearly, differences existed within the agency over what was permissible to publish and how a high-ranking former official ought to be treated.

Document 10: CIA Routing and Record Sheet, Author and Addressee Excised, “Directorate Candidate to Discuss Kermit Roosevelt Manuscript,” July 26, 1978, Non-classified; with attached Speed Letter to John McMahon, Deputy Director for Operations, from [Name Excised] DO Alternate, Publications Review Board, July 26, 1978, Internal Use Only

With internal objections to the manuscript mounting, CIA officials geared up reluctantly for the next round of negotiations with Roosevelt. The speed letter author reminds John McMahon, the agency’s senior operations officer, that the Information Management Staff has unearthed “major problems” with the book. “Out of consideration for Roosevelt’s role in the events that he describes,” the letter’s author offers a concession of sorts by proposing to include a DO (Directorate of Operations) representative to help with the briefing of Roosevelt. Agency officials clearly believe they have right on their side, not least from a legal standpoint, but the collective distaste for what is to come is palpable. For one thing, the prospect of litigation looms. For another, Roosevelt is subtly making it difficult for the agency, i.e. by agreeing to meet but only at his summer home on Nantucket. There is obvious internal reluctance to take on the assignment, as the letter notes at least two officials have turned it down. McMahon does not show much sympathy in the face of this test of agency flexibility. Handwritten on the routing sheet is his bottom line: “I will not approve any publication which in any way refers to CIA activities abroad.”

Document 11: CIA Routing and Record Sheet for Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, Director of Central Intelligence, et al, from Director of Public Affairs [Name Excised], “Expected Problem on Book by Former Agency Employee,” circa August 14, 1978, Confidential; with attached Memorandum for Director of Central Intelligence, from Herbert E. Hetu, Director of Public Affairs, “Expected Problem on Book by Former Agency Employee,” August 14, 1978, Secret; and Memorandum for Chairman of Publications Review Board, from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt’s Book on Iran,” August 4, 1978, Secret

Two weeks later, the “problem” of Roosevelt’s book reaches the top ranks of the CIA. This group of documents warns Director Stansfield Turner and Deputy Director Frank Carlucci that Roosevelt is balking at agency demands and might try to approach them directly or through high-level friends. The second attached memo records an August 2 meeting — on Nantucket — involving Roosevelt, his son Jonathan, a DO official (Campbell James, who is named in the chronology attached to Document 18), and a lawyer from the Office of General Counsel.

After “pleasantries,” according to the second memo, the CIA officials deliver DDO John McMahon’s stern message that no mention of CIA operations overseas will be tolerated. “This explanation of the DDO’s position shocked the Roosevelt gentlemen,” the memo relates. “The book has cost me two years of my life,” Kermit responded, “Why wasn’t I told earlier?” He reminds the officials he has already discussed the book with former DCI Bush and had the Shah’s consent, too. The AGC insists no-one is challenging these points (although the routing sheet does), but adds “the Agency had different management today and different ground rules concerning publication of manuscripts.”

The AGC goes on to cite Turner’s recent testimony in a legal case involving controversial former agent Frank Snepp who he says did not submit a book to prior review and as a result, “diminished the world-wide confidence in our ability to protect secrets.” He also cites Federal Judge John J. Sirica to the effect that the proper test of classification is not the age of the information but its “present impact.” (Both points remain standard intelligence community arguments today.)

Unlike previous conversations with the Roosevelts, this one ends on a less friendly note. “I received the distinct impression from Jonathan Roosevelt’s reaction that he might very well advise his father to proceed with publication of the book without securing Agency approval.” He sees it as “very likely” the family will use their access to “senior officials in the legislative branch or executive branch” to intercede with DCI Turner. He adds his suspicion that the Roosevelt family is “counting on” a “substantial amount of money” coming from both book and movie rights.

At the top of the first memo, Turner writes in longhand: “I’m still interested in all other books published by former employees w/o clearance.”

Document 12: Memorandum for Chairman, Publications Review Board, from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt’s Draft: 28 Mordad: The Countercoup,” September 28, 1978, Non-classified

In this update for the PRB, the AGC advises that the Roosevelt family wants to meet again. (The meeting is planned for October 2, but the agency decides to cancel it, according to a subsequent document, “until CIA gets its act together” — see Document 18.) Continuing to anticipate a court fight, the Office of General Counsel has been discussing what it will need to prevail, and the author relays this information to the chairman of the PRB. The agency “will not be able to defend” DDO McMahon’s “blanket prohibition” (see Document 10), he writes. Instead, the PRB will have to provide detailed justifications for each segment they want kept out of the book. “[T]he only information which the Agency can request to be deleted from a manuscript is information which is classified, information which was learned during the course of Agency employment by the author and information which has not [been] placed in the public domain by the United States Government.” McMahon’s ban would likely be considered “an impermissible standard,” which along with the fact that Roosevelt had submitted his work for review would probably mean, in the General Counsel’s view, “that we would have no legal recourse” against Roosevelt. The author hopes the PRB will put together the required material “quickly” so that it can be used in the upcoming meeting with the Roosevelt family.

Document 13: Memorandum for Chairman, Publications Review Board, from William F. Donnelly, “Mr. Kermit Roosevelt’s Draft: 28 Mordad: The Countercoup,” October 12, 1978, Secret

In response to the above request (Document 12), the chief of the Information Management Staff dispatches this 12-page memo to the chairman of the PRB. It insists the grounds for objecting to Roosevelt’s manuscript never centered around DDO McMahon’s “blanket prohibition” but on other “principles.” The memo proceeds to lay out 156 specific objections, indicating the number could be higher if those items were to be “linked with … material that precedes or follows.” It concludes that “the manuscript is, in sum, a substantial collection of still classified material, presumably gathered essentially during the author’s period of service with the Agency.” Among the broad categories singled out are the identities of sources, the locations of CIA stations, cryptonyms, and “relations of an intelligence nature with specific countries.” (All are frequently invoked to the present day by the intelligence community.) An attachment to the memo features a 7-page chart listing the various objections.

Document 14: Memorandum for Publications Review Board, from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt Manuscript,” October 20, 1978, Secret

The AGC reports on his latest meeting with Kermit Roosevelt and another son, Kermit Jr. The attorney and an accompanying Information Management Staff officer (Robert Owen, according to the cc: line in this document and Document 15) explained what the Agency considered classified, adding the interesting suggestion that “it was possible that Mr. Roosevelt could write a different version of the same events and that the new version would not be considered classified.” (Even so, a fresh review would be required.) When Roosevelt indicated he wanted to talk things over with his editor, he was told he could not because of the terms of his secrecy agreement. Roosevelt shows a willingness to take account of the current upheaval in Iran when considering the timing of publication, and the meeting closes with the AGC feeling more confident about a positive conclusion to the entire matter.

Document 15: Letter to [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, from Kermit Roosevelt, December 18, 1978, Non-classified

Almost a year after first submitting parts of his manuscript to the CIA, an exasperated Roosevelt tells the agency he believes he has fulfilled his obligations and intends to go ahead with publication. Even though many of the CIA’s objections are “unreasonable,” he says he has adopted a number of changes “in an effort to preserve the cooperative mode we established.” Having met the “spirit of your objectives,” he declares, “In the present situation I think it would be inappropriate to go back yet again to the Government of Iran” for approval. (He reminds the AGC that the original idea for the book came from the Shah’s late Court Minister, Assadollah Alam, almost three years earlier.) Pleading an overdue commitment to McGraw-Hill, he says he “must proceed” with the publication, although he does offer to show it to the agency one more time if necessary, and again requests a rush review.

Document 16: Memorandum for Publications Review Board, from [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt Manuscript,” December 21, 1978, Secret

The AGC reports on the latest news, including his receipt of Roosevelt’s December 18 letter (Document 15). Despite Roosevelt’s hope that the matter has been settled, the attorney urges the DDO to re-review the manuscript and verify that the author has complied with agency requests. In the attached brief memo written the same day, PRB Chairman Herbert Hetu forwards the request to the DDO, asking for a turnaround of just six days, per Roosevelt’s request.

Document 17: Memorandum for [Name Excised], Office of General Counsel, from William F. Donnelly, “Manuscript ‘Countercoup’,” May 1, 1979, Secret, with attached Speed Letter for C/IMS from [Name Excised], “Galley Proofs of ‘Countercoup’,” April 30, 1979, Non-classified

Despite Roosevelt’s fondest wishes, the review process did not end with his final draft manuscript. Here, Information Management Staff Chief Donnelly attaches a speed letter from a colleague with the IMS office’s comments on the galley proofs. There seem to be only a handful of remaining items. Interestingly, two of them have not been excised, unlike the details of most of the other documents in this compilation. [Both requested changes appear in the published volume – Editor.] With some satisfaction, the speed letter writer comments: “Basically, Roosevelt has reflected quite faithfully the changes that we suggested to him. This has become, therefore, essentially a work of fiction.”

Document 18: Memorandum for the Record, [Name Excised], Associate General Counsel, “Kermit Roosevelt’s Book,” May 9, 1979, Non-classified, with attached “Chronology of Kermit Roosevelt Case,” Non-classified

The AGC records his final meeting with Roosevelt on May 7, at which the two go over the last objections raised by the agency (Document 17), and Roosevelt agrees to make the changes. Roosevelt notes he is now contemplating another book — which he promises to submit for prior review. The chronology of the case attached this memo offers some useful details not included in the other documents.

Document 19: Memorandum for The Honorable Cyrus R. Vance, from Stansfield Turner, “Impact of the Publication of Kermit Roosevelt’s Book ‘Counter Coup’,” December 13, 1979, Secret

Before the book can be published, another hurdle arises when crowds overrun the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, and take its American occupants hostage. In this memo to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance six weeks into the crisis, DCI Stansfield Turner reports that Roosevelt has agreed to hold off publication until six weeks after the hostages’ release. In fact, McGraw-Hill eventually goes forward with publication of the revised version — complete with reinstated references to British intelligence — in September 1980, four months before the end of the crisis.[5]

For more information contact:

202/994-7000 or [email protected]

NOTES

[1] David Ignatius, “The Coup Against ‘Countercoup’: How A Book Disappeared,” The Wall Street Journal, November 6, 1979, p. 1.

[2] For contemporaneous background, see: Ibid.; Herbert Mitgang, “Publisher ‘Correcting’ Book on C.I.A. Involvement in Iran,” The New York Times, November 10, 1979; Thomas Powers, “A Book Held Hostage,” The Nation, April 12, 1980, p. 437; Nancy E. Gallagher and Dunning S. Wilson, “Suppression of Information or Publisher’s Error?: Kermit Roosevelt’s Memoir of the 1953 Countercoup, with Addendum, “Countercoup II,” by Nikki K. Keddie, Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, Vol. 15, No. 1 (July 1981), pp. 14-17; Richard W. Cottam, “Countercoup: The Struggle for the Control of Iran by Kermit Roosevelt,” (book review), Iranian Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3/4 (Summer-Autumn 1981), pp. 269-272.

[3] See John Prados, The Family Jewels: The CIA, Secrecy, and Presidential Power (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), pp. 236-240.

[4] Irvin Molotsky, “Kermit Roosevelt, leader of C.I.A. Coup in Iran, Dies at 84,” The New York Times, June 11, 2000; Geoff Simons, “Iran,” The Link, Vol. 38, Issue 1, January-March 2005, p. 6.