If Quantitative Easing Works, Why Has It Failed to Kick-Start Inflation?

Quantitative easing (QE) was supposed to stimulate the economy and pull us out of deflation.

But the third round of quantitative easing (“QE3″) in the U.S. failed to raise inflation expectations.

And QE hasn’t worked in Japan, either. The Wall Street Journal noted in 2010:

Nearly a decade after Japan’s central bank first experimented with the policy, the country remains mired in deflation, a general decline in wages and prices that has crippled its economy.

***

The BOJ began doing quantitative easing in 2001. It had become clear that pushing interest rates down near zero for an extended period had failed to get the economy moving. After five years of gradually expanding its bond purchases, the bank dropped the effort in 2006.

At first, it appeared the program had succeeded in stabilizing the economy and halting the slide in prices. But deflation returned with a vengeance over the past two years, putting the Bank of Japan back on the spot.

So why didn’t quantitative easing work in Japan? Critics say the Japanese central bank wasn’t aggressive enough in launching and expanding its bond-buying program—then dropped it too soon.

***

Others say Japan simply waited too long to resort to the policy.

But Japan has since gone “all in” on staggering levels of quantitative easing … and yet is still mired in deflation.

The UK engaged in substantial QE. But inflation rates are falling there as well.

And China engaged in massive amounts of QE. But it’s also falling into deflation.

Indeed, despite massive QE by the U.S., Japan and China, there is now a worldwide risk of deflation.

So why hasn’t it worked?

Traders Weigh In

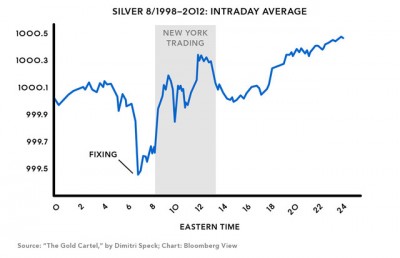

Financial commentator, trader, and inventor of high-frequency trading Max Keiser has argued for months that QE’s failure can be explained by the following 4 steps:

(1) QE throws easy cash at the zombie banks

(2) The big banks use the easy cash to speculate instead of becoming more stable … or lending out to Main Street

(3) The speculation and lack of lending decreases the vitality of the real (Main Street) economy

(4) This leads to deflation, rather than inflation

There’s some evidence that Keiser is right.

Forecaster and trader Martin Armstrong writes today:

The evolution of the monetary system of Rome illustrates how empires rise. It also reflects that the dominant economy’s currency is ALWAYS used by surrounding nations. Consequently, history demonstrates WHY in fact QE1-3 failed to produce inflation for the dollars created were absorbed globally. Theories that only view the dollar from a domestic isolated perspective are incorrect and will always fail for that is not what history teaches us if we take the time to listen.

In other words, Armstrong argues that QE falsely assumes that printed money will stay in the national economy … but printed dollars end up abroad. He explained earlier this week:

The expansion of the money supply of dollar has FAILED to produce any inflation BECAUSE the old theories have failed to take into consideration the global nature of the world economy and its demand for the currency of the current Financial Capital of the World.

***

The US cannot print enough money to meet the world demands.

There’s some evidence that Armstrong is right.

Economists Weigh In

Neither Keiser nor Armstrong are trained economists. But several high-powered economists haveweighed in on the question.

Ed Yardeni – a former Federal Reserve economist who held positions at the Fed’s Board of Governors and the Treasury Department, who served as Chief Investment Strategist for Deutsche Bank, and was Chief Economist for C.J. Lawrence, Prudential Securities, and E.F. Hutton – notes that economists including Ben Bernanke have known for 20 years that there is no transmission mechanism by which QE stimulates the real economy.

The Telegraph noted in June:

The question is why the world economy cannot seem to shake off this “lowflation” malaise, even after QE on unprecedented scale by the US, Britain, Japan and in its own way Switzerland.

***

Narayana Kocherlakota, the Minneapolis Fed chief, suggested as far back as 2011 that zero rates and QE may perversely be the cause of deflation, not the cure that everybody thought. This caused consternation, and he quickly retreated.

Stephen Williamson, from the St Louis Fed, picked up the refrain last November in a paper entitled “Liquidity Premia and the Monetary Policy Trap”, arguing that that the Fed’s actions are pulling down the “liquidity premium” on government bonds (by buying so many). This in turn is pulling down inflation. The more the policy fails – he argues – the more the Fed doubles down, thinking it must do more. That too caused a storm.

The theme refuses to go away. India’s central bank chief, Raghuram Rajan, says QE is a beggar-thy-neighbour devaluation policy in thin disguise. The West’s QE caused a flood of hot capital into emerging markets hunting for yield, stoking destructive booms that these countries could not easily control. The result was an interest rate regime that was too lax for the world as a whole, leaving even more economies in a mess than before as they too have to cope with post-bubble hangovers.

The West ignored pleas for restraint at the time, then left these countries to fend for themselves. The lesson they have drawn is to tighten policy, hoard demand, hold down their currencies and keep building up foreign reserves as a safety buffer. The net effect is to perpetuate the “global savings glut” that has starved the world of demand, and that some say is the underlying of the cause of the long slump. “I fear that in a world with weak aggregate demand, we may be engaged in a futile competition for a greater share of it,” he said.

The Bank for International Settlements [the “central banks’ central bank”] says the world is suffering from addiction to stimulus. “The result is expansionary in the short run but contractionary over the longer term. As policy-makers respond asymmetrically over successive financial cycles, hardly tightening or even easing during booms and easing aggressively and persistently during busts, they run out of ammunition and entrench instability. Low rates, paradoxically, validate themselves,” it said.

Claudio Borio, the BIS’s chief economist, says this refusal to let the business cycle run its course and to purge bad debts is corrosive. The habit of turning on the liquidity spigot at the first hint of trouble leads to “time inconsistency”. It steals growth and prosperity from the future, and pulls the interest rate structure far below its (Wicksellian) natural rate. “The risk is that the global economy may be in a deceptively stable disequilibrium,” he said.

Mr Borio worries what will happen when the next downturn hits. “So far, institutional set-ups have proved remarkably resilient to the huge shock of the Great Financial Crisis and its tumultuous aftermath. But could (they) withstand yet another shock?” he said.

“There are troubling signs that globalisation may be in retreat. There is a risk of yet another epoch-defining and disruptive seismic shift in the underlying economic regimes. This would usher in an era of financial and trade protectionism. It has happened before, and it could happen again,” he said.

The Economist reported last year:

Is QE deflationary? Yes, quite obviously so. Consider:

- A central bank that is deploying QE is almost certainly at the zero lower bound.

- QE will only help get an economy off the zero lower bound if paired with a commitment to higher future inflation.

- If a central bank is deploying QE over a long period of time, that means it has not paired QE with a commitment to higher future inflation.

- Prolonged QE is effectively a signal that the central bank is unwilling commit to higher inflation.

- QE therefore reinforces expectations that economic activity will run below potential and demand shocks will not be completely offset.

- QE will be associated with a general disinflationary trend.

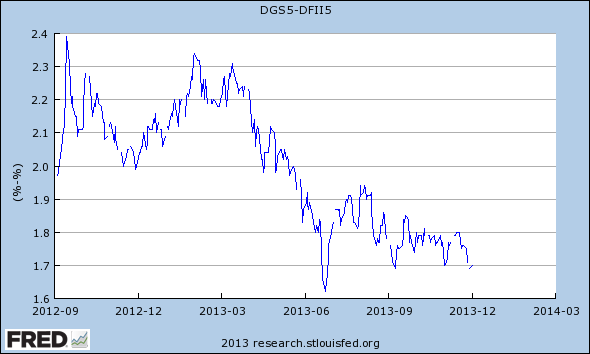

Don’t believe me? Here is a chart of 5-year breakevens since September of 2012, when the Fed began QE3, the first asset-purchase plan with no set end date:

(The article then goes onto say that QE can be deflationary or inflationary depending on what else the central bank is doing.)

Michala Marcussen – global head of economics at Société Générale – believes that QE may be deflationary in the long run because:

Excess capacity is deflationary and the means to deal with it is to shut it down. Indeed, we expect China [which also engaged in massive QE] for now to exert deflationary pressure on the global economy.

***

Unproductive investment is by nature ultimately deflationary. This is a point also worth recalling when investing in paper assets fuelled by QE liquidity and not underpinned by sustainable economic growth.

Prominent economist John Cochrane thinks he knows why. As he explained last year:

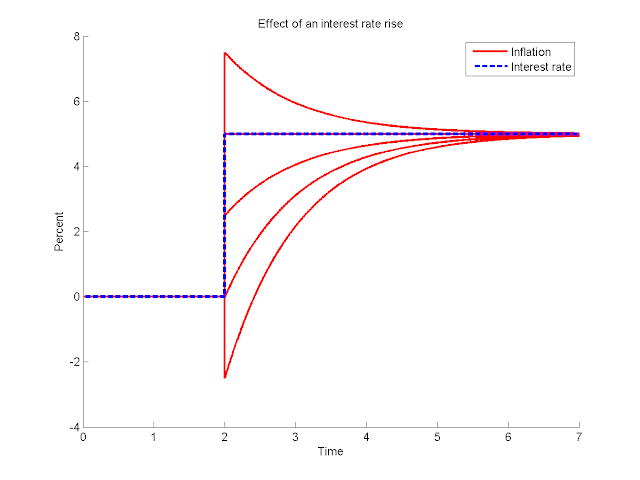

Here I graphed an interest rate rise from 0 to 5% (blue dash) and the possible equilibrium values for inflation (red). (I used κ=1 ρ=1 ).

As you can see, it’s perfectly possible, despite the price-stickiness of the new-Keynesian Phillips curve, to see the super-neutral result, inflation rises instantly.

***

Obviously this is not the last word. But, it’s interesting how easy it is to get positive inflation out of an interest rate rise in this simple new-Keynesian model with price stickiness.

So, to sum up, the world is different. Lessons learned in the past do not necessarily apply to the interest on ample excess reserves world to which we are (I hope!) headed. The mechanisms that prescribe a negative response of inflation to interest rate increases are a lot more tenuous than you might have thought. Given the downward drift in inflation, it’s an idea that’s worth playing with.

Bloomberg noted in November:

Now, the Neo-Fisherites [including Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota] have been joined by a very heavy hitter — University of Chicago economist John Cochrane. In a new paper called “Monetary Policy with Interest on Reserves,” he explains a mechanism by which higher interest rates raise inflation. Unlike Williamson’s model, Cochrane’s model obtains a Neo-Fisherian result without appealing to fiscal policy. In fact, he finds that in some cases, raising interest rates can even stimulate the economy in the short term! He concludes succinctly:

The basic logic is pretty simple: raising nominal interest rates either raises inflation or raises real interest rates. If it raises real interest rates, it must raise consumption growth. The prediction is only counterintuitive because for so long we have persuaded ourselves of the opposite[.]

Cochrane has a simple explanation of the model’s key predictions on his blog. He hypothesizes that now that the Fed pays interest on the reserves that banks hold with the Fed, monetary policy will be even more Neo-Fisherian — i.e., even more perverse.

***

Cochrane’s arguments are based on simple equations that are at the heart of most modern macroeconomic models. If the Neo-Fisherites are right, then everything the Fed has been doing to try to stimulate the economy isn’t just useless — it’s backward.

Now, the overwhelming majority of empirical studies tell us that QE, and Fed easing in general, tends to raise inflation in the short term. But what if that’s at the cost of lower inflation in the long term? Japan has been holding interest rates at zero for many years, and its economy has been in and out of deflation. Massive QE has noticeably failed to make the U.S. hit its 2 percent inflation target. What if mainstream macroeconomics has it all upside down, and prolonged periods of low interest rates trap us in a kind of secular stagnation that is totally different from the kind Harvard economist Larry Summers talks about?

It’s a disquieting thought.

One of the main architects of Japan’s QE program – Richard Koo – Chief Economist at the Nomura Research Institute – explains that QE helps in the short-run … but hurts the economy in the long run(via Business Insider):

Initially, long-term interest rates fall much more than they would in a country without such a policy, which means the subsequent economic recovery comes sooner (t1). But as the economy picks up, long-term rates rise sharply as local bond market participants fear the central bank will have to mop up all the excess reserves by unloading its holdings of long-term bonds.

Demand then falls in interest rate sensitive sectors such as automobiles and housing, causing the economy to slow and forcing the central bank to relax its policy stance. The economy heads towards recovery again, but as market participants refocus on the possibility of the central bank absorbing excess reserves, long-term rates surge in a repetitive cycle I have dubbed the QE “trap.”

In countries that do not engage in quantitative easing, meanwhile, the decline in long-term rates is more gradual, which delays the start of the recovery (t2). But since there is no need for the central bank to mop up large quantities of funds, everybody is no more relaxed once the recovery starts, and the rise in long-term rates is far more gradual. Once the economy starts to turn around, the pace of recovery is actually faster because interest rates are lower. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Indeed, things which temporarily goose the economy in the short-run often kill it in the long-run … such as suppressing volatility.

Postscript: Quantitative easing fails in many other ways, as well …

The original inventor of QE – and the former long-term head of the Federal Reserve– say that QE has failed to help the economy. Numerous academic studies confirm this. And see this.

Economists also note that QE helps the rich … but hurts the little guy. QE is one of the main causes ofinequality (and see this and this). And economists now admit that runaway inequality cripples the economy. So QE indirectly hurts the economy by fueling runaway inequality.

A high-level Federal Reserve official says QE is “the greatest backdoor Wall Street bailout of all time”. And the “Godfather” of Japan’s monetary policy admits that it “is a Ponzi game”.

Note: Financial experts have been debating since the start of the 2008 financial crisis whether inflationor deflation is the bigger risk. That debate is beyond the scope of this essay. However, it might not be either/or. We might instead have “MixedFlation” … inflation is some asset classes and deflation in others.