How to Close Gitmo: A Roadmap

Reprieve delivers justice and saves lives, from death row to Guantánamo Bay.

Executive Summary

The military prison at Guantánamo Bay is now facing the worst crisis of the Obama presidency. This roadmap explains how to defuse it and, ultimately, to close the prison.

In a closely-watched speech at the National Defense University, the President pledged to do more to shut Guantánamo. “I know the politics are hard,” he said. “But history will cast a harsh judgment on this aspect of our fight against terrorism and those of us who fail to end it. Imagine a future 10 years from now or 20 years from now when the United States of America is still holding people who have been charged with no crime on a piece of land that is not a part of our country.”1

President Obama was correct. But while his speech set out essential first steps – lifting the moratorium on transfers to Yemen, pledging to reopen the shuttered State Department Guantánamo office – there is much more that could feasibly be done now to close the prison. More will have to be done if Guantánamo is not to be with us a decade from now.

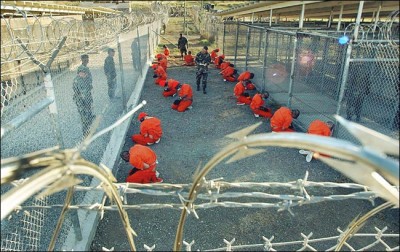

Today there are over 130 prisoners on hunger strike at Guantánamo. The strike is unprecedented in its scale and duration – it is now over four months old, with more than forty men being force-fed. The President was right to decry these force-feeding techniques as they violate both medical ethics and law. However they are likely to continue until prisoners are released, or until prisoners die, which would be a disaster from a moral and geopolitical perspective. Decisive action from the White House is more urgent than ever.

To be sure, the Bush administration bequeathed this administration significant difficulties in Guantánamo. But in many cases the situation is not as complicated as claimed, particularly if the President is serious in his claim that he is willing to take on the hard politics. The key to solving the problem is to prioritize the easier cases, while creating systems to resolve those thought to be more complex in the medium term.

In brief, the Administration must take the following steps:

- Announce the appointment of a White House official responsible for Guantánamo.

- Ensure that the White House Official and the new envoys collaborate closely with counsel for the detainees, UN-sponsored rehabilitation personnel and others seeking the same goal: the closure of Guantánamo Bay.

- Immediately appoint an independent rapporteur who reports directly to the White House official, charged with resolving the complaints of the detainees in conjunction with the JTF-GTMO command.

- Charge Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel to start issuing ‘national security waivers’ for the 86 detainees who have been cleared (some for almost a decade, most by both the Bush and Obama Administrations), beginning immediately with those slated to go to dependable allies (in, for example, Western Europe).

- Establish, with allies, rehabilitation centers overseen by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in various countries where detainees can and should be returned, where such institutions are necessary. Such centers exist already in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Since the majority of prisoners remaining come from Yemen, the US should swiftly agree a US- or UN-funded rehabilitation centre to house Yemeni ex-prisoners while they transition to civilian life, and transfer both ‘cleared’ and ‘conditionally cleared’ Yemenis to the centre. With the annual cost of Guantánamo now running at over $1 million per prisoner per year, it makes no economic sense not to pursue this option.

- Scrap the discredited military-commissions system and bring Article III judges and juries to Guantánamo to hold Constitutionally-compliant trials for all those who have, according to a prima facie case, committed criminal activity. There has been resistance to trying the cases on the mainland, but as they say, “If the mountain won’t come to you…” There is no constitutional prohibition against importing judges and jurors to Guantánamo Bay.

- Restart – and complete – the previous prisoner exchange talks with the Taliban for the remaining Taliban in Guantánamo.

- Re-assess all indefinite detention cases and, where feasible, transfer individuals to other countries with appropriate security guarantees. Convene the Periodic Review Boards announced by Executive Order 13567 to determine whether these men should remain in “continued detention” under constitutional principles of justice and in good conscience. Extend Article III trials to the individuals currently in this category, and if the evidence against them cannot sustain a conviction, release them.

- Work with Congressional allies to loosen, and eventually repeal, the restrictions on prisoner transfer contained in the last several National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs). If negotiation fails, veto the NDAA. Congress has more political exposure on this than the President.

STEP 1: Announce the appointment of a White House official responsible for Guantánamo.

This is the most straightforward step, and will send the message that the administration is serious about this second push on Guantánamo. In his speech at NDU, President Obama stated only that he would appoint “a new senior envoy at the State Department and Defense Department whose sole responsibility will be to achieve the transfer of detainees to third countries.”

White House officials have briefed journalists that chief counterterrorism Lisa Monaco has been selected as the White House appointee.2 Ms. Monaco is an excellent choice, but this should be formally announced to signal the White House’s resolve.

STEP 2: Ensure that the White House official and the new envoys collaborate closely with counsel for the detainees, UN-sponsored rehabilitation personnel and others seeking the same goal: the closure of Guantánamo Bay.

Another principle that should guide the Administration going forward is for Ms. Monaco and the new DOS/DOD envoys to work more closely with security-cleared counsel for the prisoners and other allies. In the past, we saw sporadic and individual cooperation with the State Department that resulted in successful resettlements (e.g., in the case of the Uighurs to Bermuda). But this was not comprehensive and the Government sometimes worked at cross-purposes with others who were trying to achieve the same goal.

There are several reasons to work more closely with detainees’ lawyers and others who have been charged with seeking a Guantánamo solution.

One, representatives often have links to foreign governments (especially in Europe), and may be alert to possibilities (or resistances) that the US State Department does not know.

Two, the lawyers best know their clients’ histories and needs, and the transfer process will work more swiftly and smoothly if the Administration takes a collaborative approach to resettlements. Previous transfer efforts failed sometimes where a European government, working with the lawyers, suggested a prisoner or prisoners who needed resettlement to the State Department. The State Department, missing key information, then proposed a different prisoner who ultimately rejected the settlement offer. No one ultimately went to the country in question. These are wasted opportunities the Administration can ill afford.

Counsel can also play a vital role in other ways, including in persuading the clients to accept voluntary security arrangements upon their transfer to another country – arrangements that simplify the certification process. However, counsel cannot play this role without concrete signs that the Administration is moving, and moving swiftly, to address the crisis at the base. Promises have been made before, and promises have not been kept. Counsel cannot risk destroying their own relationship of trust with the detainees without real promise of a solution.

STEP 3. Immediately appoint an independent rapporteur who reports directly to the White House official, charged with resolving prisoners’ complaints in conjunction with the JTF-GTMO command.

Any trust that existed between the guards and the guarded in Guantánamo has broken down – almost irrevocably given the severe response to the non-violent hunger strike, now in its fifth month. Guantánamo is, perhaps, the most difficult prison to run on the planet, given its catastrophic international reputation, the limbo in which most detainees find themselves, and the history of harsh conditions. Unfortunately, JTF-GTMO has been plagued by constant changes in personnel, and the assignment of senior officers who had no institutional memory and little relevant experience in corrections.

The prison is currently at its nadir, with the overwhelming majority of the detainees on a hunger strike, and virtually all the others (mainly the infirm) supportive of it. Prisoners recognize that the goal of their hunger strike – ending their detention without trial, particularly of those long cleared – is, ironically, supported by President Obama. However, the detainees have little reason to trust the latest Administration promise that action will be taken: after all, releases have been far slower than in the Bush Administration, and since the start of 2011 have ground to a halt.

The hunger strike – particularly the notion of peaceful protesters being fed against their will – has already been a public relations disaster for the United States, sharpening the negative effects of the original Guantánamo experiment. The catastrophe will only worsen when, as is likely in a strike of this scale and duration, prisoners become irretrievably ill or die. The only way to avert this is to persuade the detainees that a solution is coming. Again, counsel can be an ally in this, but the situation at the prison has so deteriorated that it needs an independent official to step into the fray.

This would be the task of the independent rapporteur. In the rapporteur, prisoners and counsel would have an ombudsman: a trusted official independent from the camp administration, who receives, investigates, and addresses prisoners’ complaints. The Administration earned a reputation for trying to improve conditions at the base early in President Obama’s tenure. Despite the considerable obstacles, the rapporteur would help to restore that trust.

Perhaps the most important step, and the only one likely to get large numbers of prisoners to eat again, is the next one: the signing of waivers and transfer of cleared prisoners.

STEP 4: Charge Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel to start issuing ‘national security waivers’ for the 86 cleared people, beginning with those slated to go to close allies (in, for example, Western Europe).

This is the single most important step the Administration can take. It is also the best hope of defusing the current crisis at Guantánamo: while prisoners have indicated that a Qu’ran search initially sparked their hunger strike, many have also made plain that indefinite detention (particularly of cleared prisoners) is the fuel that keeps it going.

The Administration should begin this process immediately. As others have commented, at the current rate of transfers, Guantánamo will remain open until 2054.

The Waiver process

Section 1028(d) of the 2013 NDAA (like the 2012 NDAA) provides for waiver of the

NDAA’s certification procedures where:

it is not possible to certify that the risks … have been completely eliminated, but the actions to be taken [by the receiving country]… will substantially mitigate such risks with regard to the individual to be transferred … and [that] the transfer is in the national security interests of the United States.

In other words, Secretary Hagel need no longer “ensure” that any detainee transferred “cannot engage in terrorist activity”. He has only to find that the receiving country has agreed to take actions that “will substantially mitigate” that risk.

The general legal consensus is that “[t]hese new waiver provisions clearly give the Administration both the legal authority and the practical ability to transfer detainees from Guantánamo to their home countries.”3 Senate Armed Service Committee Chair Carl Levin has confirmed this is the reason the waiver exists in a recent letter to the White House: “more than a year ago, I successfully fought for a national security waiver that provides a clear route for the transfer of detainees to third countries in appropriate cases.”4

Everyone ‘cleared’ by the Inter-Agency Task Force has been found appropriate for transfer by a unanimous panel from the relevant agencies. Certifications for these individuals to appropriate states should begin forthwith – beginning with some European resettlements.

Resettlement cases: fewer and fewer

While resettlement cases – cases of those who need placement in countries other than their countries of citizenship – have been described as a major ‘block’ to Guantánamo closing, in the current climate they may well be the easiest cases.

First, there are fewer of these individuals than ever – an estimated seventeen prisoners, most cleared. The Administration would do well to focus on transferring these individuals as a first step. The states most likely to respond quickly to an approach from the Obama administration for further resettlement are the US’s closest allies – particularly states in Europe, which have historically accepted the bulk of Guantánamo’s refugees.

Those same states are also the best candidates for transfers with minimal political resistance in the US. The most successful repatriations and resettlements have generally been to Western European countries. Moreover, the law enforcement and intelligence communities of Western Europe are perfectly able to ‘mitigate’ any

perceived risk – an important part of explaining any transfer to recalcitrant members of Congress. Of the many prisoners released to Britain over the past ten years, for example, there is not a single example of anyone committing any act of terrorism.

Case study

Shaker Aamer, ISN 239

British resident Shaker Aamer offers perhaps the most straightforward case, because of the position of the both the US and the UK governments. Significantly, Mr. Aamer was cleared first by the Bush Administration in 2007, and again by the Obama Administration in 2009.

Meanwhile, senior British officials have said on several occasions that they are actively seeking Mr. Aamer’s return to Britain and reunion with his British wife and four British children.

Public concern for Mr. Aamer has reached the top levels of the British government. Prime Minister David Cameron raised the case with President Obama on June 17, at the G8 summit. Mr. Cameron said in response to a Parliamentary question on June 19:

I raised the case with President Obama directly and will be writing to him about the specifics of the case and everything that we can do to expedite it. We need to show some understanding of the huge difficulties that America has faced over Guantánamo Bay. Clearly, President Obama wants to make progress on this issue and we should help him in every way that we can with respect to this individual. I will keep my Hon. Friend and the House updated on progress.5

The UK has successfully absorbed the largest number of ex-detainees of any European state, with no reported troubles or incidents. Mr. Aamer is originally from Saudi Arabia, which has had far less success in reintegrating its returning detainees.

Mr. Aamer, for his part, wishes to rejoin his family in London, and has indicated he is content to sign a security agreement modelled on the prior agreements used for earlier transfers to the UK. All this said, there is no reason in principle Secretary Hagel should not sign a waiver and send Mr. Aamer on a plane back to London within a week.

The case of Mr. Aamer is significant in other ways: he speaks fluent English, and has loudly protested both his own imprisonment and that of others who have been held without trial. He was made secretary to the short-lived prisoners’ committee in 2005, when JTF-GTMO experimented, briefly, with the Geneva Conventions’ mandate that prisoners have their own committee to give them a voice. He has been accused of instigating some of the non-violent protests including the hunger strikes. He is much disliked for this by the JTF-GTMO authorities and it would be a sure sign that the Administration means business if his case were finally resolved.

Case study

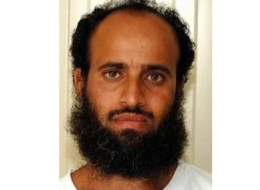

Nabil Hadjarab, ISN 238

Nabil Hadjarab, ISN 238

Nabil Hadjarab’s is also a comparatively easy case in the current climate. The Bush administration made an early approach to the French government about Mr.

Hadjarab but frosty US-France relations in the Bush years meant negotiations did not succeed. Later, the French government sought to help the Obama administration – they accepted two Algerians who had release orders from habeas hearings. Those men are living quietly in France. French authorities in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have recently indicated their willingness to discuss Mr. Hadjarab if the administration only mentions him.

By any metric France is the most appropriate option for Mr. Hadjarab: the most successful resettlements by far have been where a prisoner has existing cultural, linguistic, and familial ties to a place, and Mr. Hadjarab has all three. His father and grandfather were French colonial veterans and all his surviving family are French. His first language is French. His sense of self is French and he desires to return to France.

There are several other examples of detainees like Nabil Hadjarab and Shaker Aamer, where work by their counsel has made their relocation to another country relatively simple. Their rapid transfer is desperately needed to break the deadlock on Guantánamo.

The second category of cases that need addressing – which is by far the majority – are the cleared people who it is safe to repatriate.

Repatriation: an easier option than some believe

A number of people who were previously on the resettlement list can be safely repatriated to their countries of origin because of political changes in the intervening period. This includes, for example, cleared Tunisians and Libyans.

While it is certainly true that post-Arab spring governments are in flux, the elected representatives of these states have publicly called for the return of their nationals from Guantánamo. And while members of Congress have sought to capitalize on the violent actions of an extreme few within these states, the truth is that similar violent acts take place in the U.S. (Boston and elsewhere). The same is true of Britain (7/7 and, more recently, Woolwich), yet there has been no evidence that this is relevant to the repatriation of detainees to Britain, where ex-prisoners have behaved in exemplary fashion. Similarly, the governments of Tunisia and Libya are fundamentally pro-American and will work, along with the detainees’ lawyers, with the US to address any security concerns. Release of these nationals from Guantánamo would also burnish the US’ image in a region and at a time when it badly needs this.

Mr. Sliti, a long-cleared Tunisian national, is an ideal candidate for transfer to Tunis. Belgian counterterrorism officials comprehensively combed over his case and reached a clear conclusion: he is no religious zealot and had no connection to terrorism. (They did find, less flatteringly, that he had substance abuse problems, but his imprisonmentin Guantánamo has long since cured these.) Mr. Sliti longs simply to return to his aging parents, find work, get married, and move on from his experience in Gitmo.

Mr. Sliti, a long-cleared Tunisian national, is an ideal candidate for transfer to Tunis. Belgian counterterrorism officials comprehensively combed over his case and reached a clear conclusion: he is no religious zealot and had no connection to terrorism. (They did find, less flatteringly, that he had substance abuse problems, but his imprisonmentin Guantánamo has long since cured these.) Mr. Sliti longs simply to return to his aging parents, find work, get married, and move on from his experience in Gitmo.

The lion’s share of the work on repatriations can only be achieved by dealing with the largest remaining group of prisoners: the Yemenis. This is addressed in Step 5.

STEP 5: Establish, with allies, rehabilitation centers overseen by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in various countries where detainees can and should be returned, where such institutions are necessary. Such centers exist already in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Since the majority of prisoners remaining come from Yemen, the US should swiftly agree a US or UN-funded rehabilitation centre to house Yemeni ex-prisoners while they transition to civilian life, and transfer both ‘cleared’ and ‘conditionally cleared’ Yemenis to the centre. With the annual cost of Guantánamo now running at over $1 million per prisoner per year, it makes no economic sense not to pursue this option.

There are various countries that have illustrated their commitment to securing the return of their nationals by establishing ‘Rehabilitation Centers’ – most notably, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. These Centers provide precisely the kind of assurance the NDAA demands that the ex-prisoners will be treated appropriately and assisted in the transition back into society. Where there are assurances that an independent body (generally the ICRC) will have access to the facilities, this also provides evidence that the prisoners will not be abused upon their repatriation.

This system should be applied to Yemen. Yemen has, for some time, been treated as the most difficult country for Guantánamo transfers, because of armed unrest and the activities of a local branch of al-Qa’ida. But in many ways this is overly generalized.

Most Yemenis are no more dangerous than their British counterparts, and want to return to their families, not to any fight. Nevertheless, the Yemeni government can choose a secure location in a stable part of the country.

Moreover, keeping cleared Yemenis in limbo is widely perceived within the country as racist and unfair, fuelling the very sentiments that drive people to extremism and threaten the United States. Continuing to hold Yemenis, particularly the ‘cleared and conditionally cleared’ ones, may well be more dangerous than a carefully considered release plan.

Agree the rehabilitation center and quickly commence transfers

There is every reason to believe the rapid creation of a rehabilitation center is achievable in Yemen now, despite the fact that it stalled before. President Abdo Rabo Mansour Hadi of Yemen is generally considered a more reliable US ally on counterterrorism than his predecessor. Senior Yemeni officials from the prior administration have indicated that what destroyed plans for an earlier ‘rehab’ center in Yemen was not US unwillingness, but recalcitrance – and the quest for financial gain – on the part of deposed President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

This sort of gamesmanship is unlikely to be an obstacle in President Hadi’s Yemen. A site should be agreed (preferably an existing structure for expediency’s sake); some of the millions of dollars the US sends Yemen in counterterrorism assistance should immediately be diverted into making a credible, secure, and humane transition facility.

An element essential to making this process succeed will be to agree the center swiftly. Another will be to ensure that the ICRC has full access to the center. Transfers must be transparent and public, with assurances that men at the rehabilitation center can be met by their families as soon as they arrive. Finally, any period of detention at the facility needs a specified end date (even if the date is for a parole-style hearing), or accusations that Guantánamo has been replicated on Yemeni soil will defeat the Administration’s good work.

Case study

Samir Mukbel, ISN 04

Recently published documents in response to a FOIA request indicate that Samir Mukbel is in the category of ‘conditionally cleared’ Yemenis. Why he was not fully cleared is not obvious, given that Mr. Mukbel is among Reprieve’s meekest of clients. He spent years in Camp IV before it was closed, and to this day is a quiet, compliant soul.

It was therefore all the more extraordinary when he joined a prison-wide hunger strike in desperation at his fate.

An op-ed in the New York Times based on a telephone call between him and his counsel briefly went viral, and contributed to the hardening of US and worldwide opinion against the military’s force-feeding practices and the Administration’s perceived inaction on Gitmo.6

Samir’s family are in Ta’iz and his sole wish is to rejoin them, marry, and start a family. He would agree to join any local rehabilitation centre that meant he could see them again. Many Yemenis would do the same. A public transfer of Mr. Mukbel to a new rehabilitation center would create goodwill and might be a positive deradicalization measure.

STEP 6: Scrap the discredited military-commissions system and bring Article III judges and juries to Guantánamo to hold Constitutionally-compliant trials for all those who have, according to a prima facie case, committed criminal activity. There has been resistance to trying the cases on the mainland, but as they say, “If the mountain won’t come to you…” There is no constitutional prohibition against importing judges and jurors to Guantánamo Bay.

It is clear that parts of the Administration originally intended to hold Article III-compliant trials. Attorney General Eric Holder announced the indictment of the accused 9/11 co-conspirators in New York. Only irrational Congressional resistance scuppered this plan. US courts have a long and credible record trying terrorism cases and the one person to receive an Article III trial after his Guantánamo detention (Ahmed Ghailani) was convicted.

In any event, the putatively improved commissions system has been plagued with scandal and with intractable constitutional problems. To name just a few, the world now knows the CIA has a ‘mute’ button on the proceedings even the presiding military judge had not been told about; the military had bugged smoke detectors that they used to eavesdrop on privileged attorney-client meetings; and that dozens of defense emails have been seized by the prosecution without legal authorization.

The implication to external observers (and many US commentators) is clear: the commissions system is irretrievably broken, and will never be seen to do justice. Trials are beset with delay and often seem to stumble haplessly from one controversy to the next. Any convictions will face years of appeal, including in the federal court system. All the challenges that have thus far reached a real court have been upheld.

Reprieve appreciates that Congressional resistance makes the prospect of a facility to try and house men slated for charges in the United States difficult. But as respected commentators have suggested, there is historical precedent for running Constitutionally-compliant trials with federal judges on military bases:

Exercising his authority as commander in chief, President Harry S. Truman created a system of civilian courts in the American zone of occupation. In the 1950s, Dwight D. Eisenhower used the same power to create a special United States Court for Berlin, which remained under occupation even after the Federal Republic regained full sovereignty in western Germany. A regular federal judge presided over a criminal trial in that court as late as 1979 — a year after President Jimmy Carter gained Chief Justice Warren E. Burger’s consent to dispatch a federal district judge, Herbert J. Stern, to Berlin.

Nothing prevents President Obama from establishing a similar court at Guantánamo, where 166 prisoners remain under indefinite detention and about 100 have gone on a hunger strike. Acting under his authority as commander in chief, the president should quickly direct a team of district judges to try the detainee cases in Guantánamo under civilian criminal procedures. Such an order should also create a panel of federal judges to hear appeals.7

This is a practical and feasible solution, and one that the Administration should work to take up right away. If it clings to the commissions system it is highly likely that the cases will be in no better a posture at the close of President Obama’s final term. If, however, prisoners are convicted in a real court, then they may be transferred to the US mainland without significant problems. There will no longer be the arguably false specter of Manhattan being closed down for a trial; any post conviction hearings that may be necessary can be held inside the prison walls; and most appeals would be held before a panel of judges without the presence of the accused.

STEP 7: Restart – and complete – the previously-discussed prisoner exchange talks with the Taliban for the remaining Taliban in Guantánamo.

Prisoner exchanges are a venerable part of conflict resolution techniques, and the end of the war in Afghanistan should prove no different. Every effort should be made to resuscitate and conclude talks to transfer the (estimated five) senior Taliban left in Guantánamo, which stalled in March 2012.

Among the best reasons to do this is acknowledged in Mr. Obama’s speech: the US cannot permanently remain on a war footing after 9/11. The conflict in Afghanistan is drawing to a natural close. The wise course, as in conflicts gone by, is to negotiate these prisoner transfers as the war winds down. Does this necessitate an element of trust – or of clear-eyed acceptance of risk? To be sure. But it is also what the end of the war requires, ethically and legally.

Release of the detainees is also “seen as a crucial confidence building measure in efforts to strike a political settlement with the Taliban”.8 Such measures “strengthen the credibility of an emerging peace settlement” and “help demonstrate the viability of peace to…hard-line supporters”, thus facilitating successful negotiations.9 Prisoner exchange for individuals like Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl (the U.S. soldier held captive since 2009) is likely to be a necessary initial step.

As Rahimullah Yusufzai explains in the Danish Institute of International Studies report “Taliban Talks: Past, Present and Prospects for the US, Afghanistan and Pakistan”:

The Taliban leadership is under pressure from the rank and file and the families of the prisoners to secure their release….Because many field commanders previously were opposed to talking to the Americans…they need something to justify the talks. If the Taliban leadership can secure the release of the five prisoners, it will show the rank and file that it can achieve something through talks. Similarly, if the Americans can secure the release of their solider, Obama can show that achievement to his people”. In addition to the release of Bergdahl the U.S. could, for example, request that the Taliban stop “attacks on schools or teachers, or: “the Guantánamo prisoners will be released but you guarantee they will only operate legally as politicians””.

Release of the Taliban prisoners may have been politically unpalatable in the run-up to the 2012 election. However, this has now passed and concerns regarding the popularity of this move must yield to more urgent considerations – the likely effect of the release of these men on successful peace talks in Afghanistan.

STEP 8: Re-assess all indefinite detention cases and, where feasible, transfer individuals with appropriate security guarantees. Immediately convene the Periodic Review Boards announced by Executive Order 13567 to determine whether these men should remain in “continued detention” under constitutional principles of justice and in good conscience. Extend Article III trials to the individuals currently in this category, and if the evidence against them cannot sustain a conviction, release them.

The Guantánamo Review Task Force considered the cases of some prisoners and found that the evidence was so tainted that criminal prosecutions were impossible, but that they were nonetheless too dangerous to be released.

It is likely that in some of these cases the supposed threat is overstated, and has been made on a basis of a prisoner’s alleged acts more than a decade ago or their disciplinary record in Guantánamo. But a prisoner’s resistance to a hostile and potentially abusive guard force in, say, 2003 is a poor reason to continue to hold him indefinitely, perhaps until the end of his life.

Nor is it proper to continue to hold someone assessed to be a low threat simply because transfer would be politically problematic (for example, because the prisoner’s prior wrongful acts have been publicly overstated.) This was true in a large number of the Guantánamo prisoners’ cases, and will likely continue to be the case. But the public shame of Guantánamo’s continued existence is far greater. While the Supreme Court has, in limited circumstances, endorsed noncriminal detention for ‘the duration of hostilities’, that argument for detaining these men becomes less and less politically (and legally) credible as the war in Afghanistan winds down.

In each of these cases the best options are:

Transfer to an appropriate rehabilitation center or with appropriate monitoring from the host government.

In the cases of ‘indefinite detention’ prisoners Fawzi al Odah (ISN 232) and Faiz al-Kandari (ISN 552), for example, Kuwait has built a large and expensive rehabilitation facility for these men already. It is sitting empty. This seems unnecessary, given the close relationship between Kuwait and the US, and suggests bad faith by the US in the Gulf region.

Re-assessment of all judgments to hold prisoners indefinitely through the long-promised Periodic Review Boards (PRBs).

It bears emphasis that these PRBs must guarantee representation by the detainees’ security-cleared legal counsel. Furthermore, objectivity in review must be guaranteed and federal court review of the PRB decisions available. Otherwise, the periodic review boards will have no more legitimacy than the military commissions.

Try the remainder in Art. III processes, as with the current commissions defendants.

In the end, the only credible way to dispose of cases where men are not released after steps 1) and 2) is to hold an Article III trial, as with the individuals selected for military commissions. Fundamentally, whatever the motive, indefinite detention is seen around the world as a violation of the US’s highest constitutional principles. Questions of fact regarding a detainee’s threat level or involvement in criminal conduct must be answered at a judicial proceeding, where the burden is on the government to produce evidence that a jury will assess under traditional burdens of proof.

STEP 9: Work with Congressional allies to loosen, and eventually repeal, the restrictions on prisoner transfer contained in the last several National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs). If negotiation fails, veto the NDAA.

The NDAA is not a total bar to transfers from Guantánamo – the waiver provisions permit the transfer of many, if not most, remaining prisoners – but it is nonetheless a barrier. The President should work with allies in the House and Senate who are currently working to repeal the more onerous provisions of the NDAA. Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Carl Levin and others are working to make the process more flexible and have proposed important improvements to the next round of the NDAA.10 This effort merits the Administration’s strongest support, to include weighing in with key individual legislators.

If an acceptable version does not pass the Congress, the President should do more than threaten a veto – a threat has no credibility after the last several rounds of this legislation.

It is better to send the NDAA back to Congress.

Conclusion

With over a quarter of detainees now being force-fed, many among their number cleared, it is plain that the current situation in Guantánamo Bay is the worst detention crisis that will be faced by the Obama presidency. Action on the easier cases – cleared men targeted for Europe – is needed urgently and may well smooth the way for the remainder of the steps. Without urgent action, Gitmo’s tainted legacy will continue to haunt successive US administrations. It will undermine US foreign policy and national security objectives until it is resolved. Guantánamo habeas counsel, European and other allied governments, and a number of civil society groups stand ready to assist the Administration with this process until Guantánamo is, at last, consigned to a troubling chapter of American history.

APPENDIX

I. The Cleared 56 (List of Detainees the DOJ stated were “Cleared for Transfer in September 2012) [Reprieve clients in italics]

| ISN | Detainee’s Name | |

| 1 | 34 | Al Khadr Abdallah Muhammad Al-Yafi |

| 2 | 35 | Idris Ahmad Abdu Qadir Idris |

| 3 | 36 | Ibrahim Othman Ibrahim Idris |

| 4 | 38 | Ridah Bin Saleh Al-Yazidi |

| 5 | 152 | Asim Thabit Abdullah Al-Khalaqi |

| 6 | 153 | Fayiz Ahmad Yahia Suleiman |

| 7 | 163 | Khalid Abd Elgabar Mohammed Othman |

| 8 | 168 | Adel Al-Hakeemy |

| 9 | 170 | Sharif Al-Sanani |

| 10 | 174 | Hisham Sliti |

| 11 | 189 | Falen Gherebi |

| 12 | 197 | Younous Chekkouri |

| 13 | 200 | Saad Al-Qahtani |

| 14 | 224 | Mahmoud Al-Shubati |

| 15 | 238 | Nabil Said Hadjarab |

| 16 | 239 | Shaker Aamer |

| 17 | 249 | Mohammed Abdullah Mohammed Ba Odah |

| 18 | 254 | Muhammed Ali Husayn Khunaina |

| 19 | 255 | Said Muhammad Salih Hatim |

| 20 | 257 | Omar Hamzayavich Abdulayev |

| 21 | 259 | Fadhel Hussein Saleh Hentif |

| 22 | 275 | Abdul Sabour |

| 23 | 280 | Khalid Ali |

| 24 | 282 | Sabir Osman |

| 25 | 288 | Motai Saib |

| 26 | 290 | Ahmed Bin Saleh Bel Bacha |

| 27 | 309 | Muieen Adeen Al-Sattar |

| 28 | 310 | Djamel Ameziane |

| 29 | 326 | Ahmed Adnan Ahjam |

| 30 | 327 | Ali Al Shaaban |

| 31 | 329 | Abdul Hadi Omar Mahmoud Faraj |

| 32 | 502 | Abdul Bin Mohammed Ourgy |

| 33 | 511 | Suleiman Awadh Bin Aqil Al-Nahdi |

| 34 | 553 | Abdulkhaliq Ahmed Al-Baidhani |

| 35 | 554 | Fahmi Salem Al-Assani |

| 36 | 564 | Jalal Bin Amer Awad |

| 37 | 566 | Mansour Mohamed Mutaya Ali |

| 38 | 570 | Sabry Mohammed |

| 39 | 572 | Saleh Mohammad Seleh Al-Thabbi |

| 40 | 574 | Hamood Abdullah Hamood |

| 41 | 575 | Saad Nasir Mukbl Al-Azani |

| 42 | 680 | Emad Abdallah Hassan |

| 43 | 684 | Mohammed Abdullah Taha Mattan |

| 44 | 686 | Abdel Ghaib Ahmad Hakim |

| 45 | 689 | Mohammed Ahmed Salam Al-Khateeb |

| 46 | 690 | Abdul Qader Ahmed Hussein |

| 47 | 691 | Mohammed Al-Zarnouqi |

| 48 | 722 | Abu Wa’el Dhiab |

| 49 | 757 | Ahmed Abdel Aziz |

| 50 | 894 | Mohammed Abdul Rahman |

| 51 | 899 | Shawali Khan |

| 52 | 928 | Khiali Gul |

| 53 | 934 | Abdul Ghani |

| 54 | 1015 | Hussain Salem Mohammad Almerfedi |

| 55 | 1103 | Mohammad Zahir |

| 56 | 10001 | Belkacem Bensayah |

|

II. The Conditionally Cleared 301 [Reprieve Clients in Italics] |

||

| ISN | Detainee’s Name | |

| 1 | 26 | Fahed Abdullah Ahmad Ghazi |

| 2 | 30 | Ahmed Umar Abdullah al-Hikimi |

| 3 | 33 | Mohammed Al-Adahi |

| 4 | 40 | Abdel Qadir Al-Mudafari |

| 5 | 43 | Samir Naji Al Hasan Moqbil |

| 6 | 88 | Adham Mohamed Ali Awad |

| 7 | 91 | Abdel Al Saleh |

| 8 | 115 | Abdul Rahman Mohammed Saleh Nasir |

| 9 | 117 | Mukhtar Anaje |

| 10 | 165 | Adil Said Al Haj Ubayd Al-Busayss |

| 11 | 167 | Ali Yahya Mahdi |

| 12 | 171 | Abu Bakr ibn Ali Muhammad al Ahdal |

| 13 | 178 | Tariq Ali Abdullah Ba Odah |

| 14 | 202 | Mahmoud Omar Muhammad Bin Atef |

| 15 | 223 | Abd al-Rahman Sulayman |

| 16 | 233 | Abd al-Razq Muhammed Salih |

| 17 | 240 | Abdallah Yahya Yusif Al Shibli |

| 18 | 251 | Muhammad Said Salim Bin Salman |

| 19 | 321 | Ahmed Yaslam Said Kuman |

| 20 | 440 | Muhammad Ali Abdallah Muhammad Bwazir |

| 21 | 461 | Abd al Rahman al-Qyati |

| 22 | 498 | Mohammed Ahmen Said Haider |

| 23 | 506 | Mohammed Khalid Sali al-Dhuby |

| 24 | 509 | Mohammed Nasir Yahi Khussorf Kazaz |

| 25 | 549 | Umar Said Salim Al-Dini |

| 26 | 550 | Walid Said bin Said Zaid |

| 27 | 578 | Abdual al-Aziz Abduh Abdullah Ali Al Suwaydi |

| 28 | 688 | Fahmi Abdullah Ahmed al-Tawlaqi |

| 29 | 728 | Abdul Muhammad Nassir al-Muhajari |

| 30 | 893 | Tawfiq Nasir Awad Al-Bihani |

Notes

1 See http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-05-23/politics/39467399_1_war-and-peace-cold-war-civil-war

3 See Legal Analysis – Section 1028 of the NDAA, at http://www.closeguantanamo.org/ Articles/36-What-you-missed-the-NDAA-allows-the-President-to-release-prisoners-from-Guantanamo

6 See http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/15/opinion/hunger-striking-at-guantanamo-bay.html

7 Bruce Ackerman and Eugene Fidell, ‘Send Judges to Guantánamo, then Close it,’ New York Times, at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/04/opinion/send-civilian-judges-to-guantanamo-then-shut-it.html?_r=0

8 Elisabeth Bumiller and Matthew Rosenberg “Parents of P.O.W. Reveal U.S. Talks on Taliban Swap”, New York Times, at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/world/asia/pow-is-focus-of-talks-on-taliban-prisoner-swap.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

9 Lakhdar Brahimi and Thomas R. Pickering “Afghanistan: Negotiating Peace – The Report of The Century Foundation International Task Force on Afghanistan in Its Regional and Multilateral Dimensions”, at http://old.tcf.org/publications/pdfs/afghanistan-negotiating-peace/ AfghanTCFTaskForce%20BookComplete.pdf.

Reprieve

PO Box 72054

London EC4P 3BZ

T +44 (0)20 7553 8140 F +44 (0)20 7353 8189 www.reprieve.org.uk [email protected]

Registered Office

2-6 Cannon Street

London EC4M 6YH

Reprieve is a charitable company limited by guarantee Registered Charity No 1114900

Registered Company No 5777831

Chair

Ken Macdonald QC

Patrons

Alan Bennett

Julie Christie

Martha Lane Fox

Gordon Roddick

Richard Rogers

Ruth Rogers

Jon Snow

Marina Warner

Vivienne Westwood