How New Journalism and America’s Alternative Press Changed the Rules

By the mid-1960s most college towns had some nearby liberated zone where you could cruise and drink and dream, and along the way find out about what was shaking in the “outside world.”

For most Orangemen, the innocently sexist nickname for Syracuse University students, the place was Marshall Street, a commercial strip a few hundred feet off campus, where you could find coffee and company and “underground,” experimental, downright radical books and periodicals of every kind.

Building on a tradition that stretched back to nineteenth century literary social criticism, early twentieth century investigative journalism, utopian community newspapers, and early radical magazines like The Masses, the modern American alternative press had emerged in mid-50s New York with The Village Voice and Dissent. Within a few years, Paul Krassner launched the irreverent Realist,publishing “diabolical dialogues” that mixed fantasy and reality.

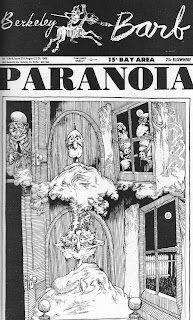

But a truly counter-cultural underground press movement would not fully blossom until the middle of the 1960s on the West Coast, and then quickly spread back across the country. After the LA Free Press, which provided a passionate voice for “the other side” – specifically youth, leftists, gays, and disaffected locals – came the Berkeley Barb, San Francisco Oracle (and later Bay Guardian), and New York’s East Village Other.

What distinguished the underground press and “new journalism” writing from their predecessors was a combination of style, focus, and values. Abandoning what looked like the pretense of “objectivity,” most alternative writers embraced advocacy or adopted a more intimate and personal prose style, concerned yet sometimes cynical, detailed and still selective. Many of the publications even looked different, merging print and avant-garde graphics in ways that the mainstream media found unprofessional and alienating to their “mass” audiences.

Max Scherr started the Berkeley Barb in 1965 to coincide with a Vietnam Day demonstration to stop troop trains. Visually uneven, sometimes shrill but always provocative, it soon reached a circulation of 90,000. The next year saw an explosion of underground papers. The San Francisco Oracle took full advantage of offset printing, the emerging photographic plate technology, to further fuse print and graphics in presenting articles on LSD, orientalia, and peace. In New York, The East Village Other adopted a more conventional layout style, but offered everything from quasi-academic pieces on Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey to underground comics and local coverage of knife fights in the city’s crime-scarred tenements.

With newspapers popping up across the country, notably Detroit’s Fifth Estate and Lansing’s The Paper, a clearinghouse for articles and ads called Underground Press Service was also established, starting with half a dozen members but reaching 200 papers and a potential audience of more than a million readers within a few years. That was followed by Liberation News Service, which sent out packages three times a week to about 360 counter-cultural and political outlets.

The psychedelic and “Marxist” wings of this nascent media movement ultimately fractured. But for a glittering moment, as activists and “hippies” looked for ways to “do your own thing” and “change the world” at the same time, there was The Rag out of Austin, perhaps the first “movement” paper – anarchist-structured and strongly anti-sexist, and The Rat, a political alternative to the East Village Other, and The Bird, with its catalog approach to tracking and backing political causes, not to mention Space City, started before a Houston anti-war demo, featuring a rotating staff and strong identification with Black and Chicano militants, and The Berkeley Tribe, born out of sectarian-inspired strikes against The Barb.

Devouring any new publication that came along, I was increasingly excited by the transformation underway in journalistic and fiction writing. Both were providing increased space for imagination, advocacy and speculation. Just as fiction drifted away from social realism, “new journalists” were breaking with the reporting of isolated events, and starting to consider context and broader social impacts. Adopting some techniques of realism, they were developing devices that gave their writings an immediacy and emotional power missing in both objective reporting and surrealist fiction.

Subjectivity, which had been common and acceptable during the nineteenth century era of “partisan” press and the turn-of-the-century “yellow journalism” period, returned under the banners of “advocacy” and the “non-fiction novel.” According to Tom Wolfe, a move from news reporting to this field led naturally to the discovery “that the basic reporting unit is no longer the datum, the piece of information, but the scene, since most of the sophisticated strategies of prose depend upon scenes.” The old rules no longer apply when a journalist takes this leap, said Wolfe, “it is completely a test of his personality.”

Reporters were turning from the exclusively “objective” concerns for verification, specificity and readability that dominated conventional journalism to the uniqueness of each experience and the writer’s impressions and intentions in becoming a witness. The presentation ranged from the polemic to the dramatic, as pioneers pondered their subjects in various aspects and relations.

Certainly, this social revolution didn’t significantly alter the way the “mainstream” press dealt with events. It did, however, expand the range of permissible expression for reporters, paralleling trends in documentary film making, where the subjective point of view has since become a powerful audio-visual tool, as well as in non-fiction writing.

In the ’60s, only a few authors dared to bring their personal experiences into consideration when writing about politics, sociology, and psychology. By the ’80s such “testimonial” touches were commonplace; in certain fields, notable pop psychology, they virtually became a requirement.

At the same moment, speculative fiction – an outgrowth of science fiction and fantasy – moved from the margins to the mainstream. The merging of surrealism and sci fi had begun with writers like Kurt Vonnegut, Ursula LeGuin, Samuel Delany, Harlan Ellison, Romain Gary and others who explored current and potential realities. Since then, this has attained the status of a highly popular genre, often affirming the view that the arithmetically predictable model of the world and universe is only one of many possibilities.

Greg Guma has been a writer, editor, historian, activist and progressive manager for over four decades. His latest book, Dons of Time, is a sci-fi look at the control of history as power.