How Does the Gates Foundation Spend its Money to Feed the World?

Bill Gates at Cornell University, trying to cross-pollinate wheat. (Photo: Cornell University)

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs. We talk to farmers about the crops they want to grow and eat, as well as the unique challenges they face. We partner with organizations that understand and are equipped to address these challenges, and we invest in research to identify relevant and affordable solutions that farmers want and will use.”

First guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.1

At some point in June this year, the total amount given as grants to food and agriculture projects by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation surpassed the US$3 billion mark. It marked quite a milestone. From nowhere on the agricultural scene less than a decade ago, the Gates Foundation has emerged as one of the world’s major donors to agricultural research and development.

The Gates Foundation is arguably the biggest philanthropic venture ever. It currently holds a $40 billion endowment, made up mostly of contributions from Gates and his billionaire friend Warren Buffet. The foundation has over 1,200 staff, and has given over $30 billion in grants since its inception in 2000, $3.6 billion in 2013 alone.2 Most of the grants go to global health programmes and educational work in the US, traditionally the foundation’s priority areas. But in 2006-2007, the foundation massively expanded its funding for agriculture, with the launch of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and a series of large grants to the international agricultural research system (CGIAR). In 2007, it spent over half a billion dollars on agricultural projects and has maintained funding at around this level. The vast majority of the foundation’s agricultural grants focus on Africa.

Image, right: A junior business advisor for TechnoServe discusses farming techniques with a Ugandan farmer. Technoserve is the NGO receiving the most funds from the Gates Foundation. It’s a US based NGO that develops “business solutions to poverty”. Running on an $80 million annual budget, it received a total of $85 million from the Gates Foundation during the last decade. Over half of these funds came through a 2007 grant “to help entrepreneurial men and women in poor rural areas of the developing world build business”. Technoserve carries out this work through partnerships with food corporations such as Cargill, Unilever, Coca Cola and Nestlé, who bring “world-class business and industry expertise” and who are offered, through the programme, “new market and sourcing opportunities”.

Image, right: A junior business advisor for TechnoServe discusses farming techniques with a Ugandan farmer. Technoserve is the NGO receiving the most funds from the Gates Foundation. It’s a US based NGO that develops “business solutions to poverty”. Running on an $80 million annual budget, it received a total of $85 million from the Gates Foundation during the last decade. Over half of these funds came through a 2007 grant “to help entrepreneurial men and women in poor rural areas of the developing world build business”. Technoserve carries out this work through partnerships with food corporations such as Cargill, Unilever, Coca Cola and Nestlé, who bring “world-class business and industry expertise” and who are offered, through the programme, “new market and sourcing opportunities”.

Spending so much money gives the foundation significant influence over agricultural research and development agendas. As the weight of the foundation’s overall focus on technology and private sector partnerships has begun to be felt in the global agriculture arena, it has raised opposition and controversy, particularly around its work in Africa. Critics say that the Gates Foundation is promoting an imported model of industrial agriculture based on the high-tech seeds and chemicals sold by US corporations. They say the foundation is fixated on the work of scientists in centralised labs and that it chooses to ignore the knowledge and biodiversity that Africa’s small farmers have developed and maintained over generations. Some also charge that the Gates Foundation is using its money to impose a policy agenda on Africa, accusing the foundation of direct intervention on highly controversial issues like seed laws and GMOs.

GRAIN looked through the foundation’s publicly available financial records to see if the actual flows of money support these critiques. We combed through all the grants for agriculture that the Gates Foundation gave between 2003 and September 20143. We then organised the grant recipients into major groupings (see table 2) and constructed a database which can be downloaded as a spreadsheet or as a more printer-friendly table from GRAIN’s website.4

Here are some of the conclusions we were able to draw from the data.

1. The Gates Foundation fights hunger in the South by giving money to the North.

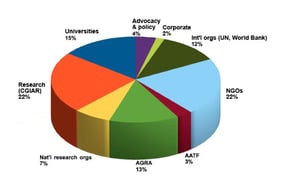

Graph 1 and Table 1 give the overall picture. Roughly half of the foundation’s grants for agriculture went to four big groupings: the CGIAR’s global agriculture research network, international organisations (World Bank, UN agencies, etc.), AGRA (set up by Gates itself) and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF). The other half ended up with hundreds of different research, development and policy organisations across the world. Of this last group, over 80% of the grants were given to organisations in the US and Europe, 10% went to groups in Africa, and the remainder elsewhere. Table 2 lists the top 10 countries where Gates grantees are located and the amounts they received, highlighting some of the main grantees. By far the main recipient country is Gates’s own home country, the US, followed by the UK, Germany and the Netherlands.

When it comes to agricultural grants by the foundation to universities and national research centres across the world, 79% went to grantees in the US and Europe, and a meagre 12% to recipients in Africa.

The North-South divide is most shocking, however, when we look at the NGOs that the Gates Foundation supports. One would assume that a significant portion of the frontline work that the foundation funds in Africa would be carried out by organisations based there. But of the $669 million that the Gates Foundation has granted to non-governmental organisations for agricultural work, over three quarters has gone to organisations based in the US. Africa-based NGOs get a meagre 4% of the overall agriculture-related grants to NGOs.

(map excludes grants to CGIAR, AGRA, AATF and international organisations)

2. The Gates Foundation gives to scientists, not farmers

As can be seen in Graph 2, the single biggest recipient of grants from the Gates Foundation is the CGIAR, a consortium of 15 international agricultural research centres. In the 1960s and 70s, these centres were responsible for the development and spread of a controversial Green Revolution model of agriculture in parts of Asia and Latin America which focused on the mass distribution of a few varieties of seeds that could produce high yields – with the generous application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Efforts to implement the same model in Africa failed and, globally, the CGIAR lost relevance as corporations like Syngenta and Monsanto took control over seed markets. Money from the Gates Foundation is providing CGIAR and its Green Revolution model a new lease on life, this time in direct partnership with seed and pesticide companies.5

Click to enlarge – Graph 2: the Gates Foundation’s $3 billion pie (agriculture grants, by type of organisation).

Click to enlarge – Graph 2: the Gates Foundation’s $3 billion pie (agriculture grants, by type of organisation).

The CGIAR centres have received over $720 million from Gates since 2003. During the same period, another $678 million went to universities and national research centres across the world – over three-quarters of them in the US and Europe – for research and development of specific technologies, such as crop varieties and breeding techniques.

The Gates Foundation’s support for AGRA and the AATF is tightly linked to this research agenda. These organisations seek, in different ways, to facilitate research by the CGIAR and other research programmes supported by the Gates Foundation and to ensure that the technologies that come out of the labs get into farmers’ fields. AGRA trains farmers on how to use the technologies, and even organises them into groups to better access the technologies, but it does not support farmers in building up their own seed systems or in doing their own research.6

We could find no evidence of any support from the Gates Foundation for programmes of research or technology development carried out by farmers or based on farmers’ knowledge, despite the multitude of such initiatives that exist across the continent. (African farmers, after all, do continue to supply an estimated 90% of the seed used on the continent!) The foundation has consistently chosen to put its money into top down structures of knowledge generation and flow, where farmers’ are mere recipients of the technologies developed in labs and sold to them by companies.

3. The Gates Foundation buys political influence

Does the Gates Foundation use its money to tell African governments what to do? Not directly. The Gates Foundation set up the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa in 2006 and has supported it with $414 million since then. It holds two seats on the Alliance’s board and describes it as the “African face and voice for our work”7.

AGRA, like the Gates Foundation, provides grants to research programmes. It also funds initiatives and agribusiness companies operating in Africa to develop private markets for seeds and fertilisers through support to “agro-dealers” (see box on Malawi). An important component of its work, however, is shaping policy.

AGRA intervenes directly in the formulation and revision of agricultural policies and regulations in Africa on such issues as land and seeds. It does so through national “policy action nodes” of experts, selected by AGRA, that work to advance particular policy changes. For example, in Ghana, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted revisions to the country’s national seed policy and submitted it to the government. The Ghana Food Sovereignty Network has been fiercely battling such policies since the government put them forward. In Mozambique, AGRA’s Seed Policy Action Node drafted plant variety protection regulations in 2013, and in Tanzania it reviewed national seed policies and presented a study on the demand for certified seeds. Also in Tanzania, its Land Policy Action Node is involved in revising the Village Land Act as well as “reviewing laws governing land titling at the district level and working closely with district officials to develop guidelines for formulation of by-laws.”8

The African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) is another Gates Foundation supported organisation that straddles the technology and policy arenas. Since 2008, it has received $95 million from the Gates Foundation, which it used to to support the development and distribution of hybrid maize and rice varieties. But it also uses funds from the Gates Foundation to “positively change public perceptions” about GMOs and to lobby for regulatory changes that will increase the adoption of GM products in Africa.9

In a similar vein, the Gates Foundation provides Harvard University University with funds to promote discussion of biotechnology in Africa, Michigan University with a grant to set up a centre to help African policymakers decide on how best to use biotechnology, and Cornell University with funds to create a global “agricultural communications platform” so that people better understand science-based agricultural technologies, with AATF as a main partner.

Gates & AGRA in Malawi: organising the agro-dealers

One of AGRA’s core programmes in Africa is the establishment of “agro-dealer” networks: small, private stockists who sell chemicals and seeds to farmers. In Malawi, AGRA provided a $4.3 million grant for the Malawi Agro-dealer Strengthening Programme (MASP) to supply hybrid maize seeds and chemical pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers.

The main supplier to the agro-dealers in Malawi has been Monsanto, responsible for 67% of all inputs. A Monsanto country manager disclosed that all of Monsanto’s sales of seeds and herbicides in Malawi are made through AGRA’s agro-dealer network.

“Agro-dealers… act as vessels for promoting input suppliers’ products,” says one MASP project document. Another states: “supply companies have expressed their appreciation for field days because MASP trained agro-dealers are helping them promote their products in the very remotest areas of Malawi.” Training the agro-dealers on product knowledge is carried out by the corporate suppliers of the products themselves. In addition, these agro-dealers are increasingly the source of farming advice to small farmers, and an alternative to the government’s agricultural extension service.

A project evaluation report states that 44% of the agro-dealers in the programme were providing extension services. According to the World Bank: “The agro-dealers have… become the most important extension nodes for the rural poor… A new form of private sector driven extension system is emerging in these countries.”The agro-dealer project in Malawi has been implemented by CNFA, a US-based organisation funded by the Gates Foundation, USAID and DFID, and its local affiliate the Rural Market Development Trust (RUMARK), whose trustees include four seed and chemical suppliers: Monsanto, SeedCo, Farmers World and Farmers Association.

Adapted from “The Hunger Games” by War on Want, London, 2012.

Listening to farmers?

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs” is the first guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture.10 But it is hard to listen to someone when you cannot hear them. Small farmers in Africa do not participate in the spaces where the agendas are set for the agricultural research institutions, NGOs or initiatives, like AGRA, that the Gates Foundation supports. These spaces are dominated by foundation reps, high-level politicians, business executives, and scientists.

Listening to someone, if it has any real significance, should also include the intent to learn. But nowhere in the programmes funded by the Gates Foundation is there any indication that it believes that Africa’s small farmers have anything to teach, that they have anything to contribute to research, development and policy agendas. The continent’s farmers are always cast as the recipients, the consumers of knowledge and technology from others. In practice, the foundation’s first guiding principle appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to farmers. In that, it looks, not surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft.

GRAIN would like to thank Camila Oda Montecinos for her help in pulling together the database and the graphic materials.

Putting your money where your mouth is

In September 2014, the Rockefeller heirs decided to follow some of their philanthropic peers and divest the money in their foundations from fossil fuels, citing moral reasons. Gates too, with his foundation holding around $700 million in shares in Exxon, BP and Shell, has been under pressure to make his investments more socially responsible.11

In 2007, the Los Angeles Times revealed that hundreds of Gates Foundation investments – totalling at least $8.7 billion, or 41% of its assets – were in companies that ran counter to the foundation’s charitable goals or social philosophy.

Shortly afterwards, the foundation announced a review of its investments to assess their social responsibility. That review, however, was quickly trashed and the foundation decided to stick with a policy of investing for maximum return.12The foundation does, however, claim that“when instructing the investment managers, Bill and Melinda also consider other issues beyond corporate profits, including the values that drive the foundation’s work”.13

It is difficult to see what that amounts to when it comes to its food and agriculture programme. The Gates Foundation maintains that “access to diverse, nutritious foods is fundamental to good health” but its food related investments go almost exclusively to the fast food industry. A stunning $3.1 billion went to companies like Coca Cola, McDonald’s, Pepsico, Burger King, and KFC in 2012. The Foundation has $1 billion tied up in the world’s largest supermarket chain, Walmart, which is a major force driving out small farms in favour of large suppliers.14 The Gates Foundation has also bought $23 million in shares of the world’s leading producer of genetically engineered crops, Monsanto.15

Table 1: Gates Foundation agricultural grants by type of grantee, 2003-2014

| Agency | $US million | Main recipients |

| CGIAR | 720 | The CGIAR is a consortium of 15 international research centres set up to promote the Green Revolution across the world. Gates is now amongst its major donors. Main recipients include: IFPRI ($167 million), CIMMYT ($132m), IRRI ($139m), ICRISAT ($76m), IITA ($49m), ILRI ($15m), CIP ($55m), CIAT ($33m) and others. Most of the grants are in the form of project support to each of the centres, and many of them are focussing on developing new crop varieties. |

| AGRA | 414 | A total of 14 grants for core support and AGRA’s main issue areas: seeds, soils, markets, and lobbying African governments to change policies and legislation. |

| Int’l orgs (UN, World Bank, etc.) | 362 | World Bank – IBRD ($119m); World Food Programme (WFP) ($79m); UNDP ($54m.); FAO ($50 m.) UN Foundation ($30m). The lion’s share of the grants to the World Bank are to promote public and private sector investment in agriculture ($60m), WFP is supported to improve market opportunities for small farmers, UNDP to establish rural agro-enterprises in West Africa, and the support to FAO is mostly for statistical and policy work. |

| AATF | 95 | AATF (African Agricultural Technology Foundation) is a blatantly pro-GMO pro-corporate research outfit based in Nairobi. Gates supported them with almost $100 m mostly to develop and distribute hybrid maize and rice varieties, but also to raise“awareness on agricultural biotechnology for improved understanding and appreciation”. |

| Universities & National Research Centres. | 678 | Over three quarters of all Gates funding to universities and research centres goes to institutions in the US and Europe, such as Cornell, Michigan and Harvard in the US, and Cambridge and Greenwich Universities in the UK, amongst many others. The work supported is a mix of basic agronomic, breeding and molecular research, as well as policy research. A lot of it includes genetic engineering. Michigan State University, for example, got $13m to help African policy makers “to make informed decisions on how to use biotechnology”.Although most of the foundation’s grants are supposed to benefit Africa, barely 12% of its grants to universities and research centres go directly to African institutions ($80m in total, of which $30m for the Uganda based Regional University Forum set up by the Rockefeller Foundation. |

| Service delivery NGOs | 669 | The Gates Foundation sees these as agents to implement its work on the ground. They include both large development NGOs and foundations, and the activities supported tend to have a strong technology development angle, or focus on policy and education work in line with the foundation’s philosophy. A whopping 76% of these grants end up with beneficiaries in the US, and another 13% in Europe. African NGOs get 4% of the NGO grants ($28m total, $13m of which to groups in South Africa, and another $13m for “Farm Concern International” an NGO based in Nairobi with the mission of creating “commercialized smallholder communities with increased incomes for improved, stabilized & sustainable livelihoods in Africa and beyond”. |

| Corporations | 50 | A relatively minor share of Gates’ funding goes directly to the corporate sector. Most of the grants are for specific technologies developed by the corporations in question. The two single largest grants ($23m and $9m) are to the World Cocoa Foundation, a corporate outfit representing the worlds major food and cocoa processors, for (amongst other things) “grants to industry players who will focus on improving the productivity of cocoa”. |

| Advocacy & policy | 122 | Here we find a mix of groups working on policy issues to support the Gates Foundation’s agenda, especially in Africa. The two largest grants are for the Meridian Institute in the USA, ($20m) to “develop an Africa-based and Africa-led partnership” and to FANRPAN, a policy research network based in South Africa ($16m) to set up “nutrition sensitive agriculture programs” in sub-Saharan Africa.Please note that much of the foundation’s policy and advocacy work is implemented through grants to institutions in the other groups (such as Universities, the CGIAR and, most notably, AGRA), to get African policy makers to change seed, land, IPR and other laws to favour corporate investment and technology introduction. |

| Total | 3110 |

Table 2: Gates Foundation agricultural grant recipients, top 10 countries 2003-2014

(excluding: grants to CGIAR, AGRA, AATF and Int’l organisations)

| Country | $US million | Main recipients |

| USA | 880 | By far the largest recipient country of Gates agricultural grants meant to benefit farmers in poor countries: $880 million dished out in 254 grants. Recipients include US universities and research institutions to produce for crop varieties and biotechnology research for farmers in Africa (e.g. Cornell University, $90m in 12 grants), big NGO projects mostly oriented to develop technology and markets (e.g. Heifer, $51m, to increase cow productivity and Technoserve Inc., $47m, to help poor farmers to “build business that create income”), and several policy and capacity building projects to push the foundation’s agenda in Africa and elsewhere. |

| UK | 156 | A total of 25 grants with a focus on academic research such as for the University of Greenwich to work on cassava value chains in several African countries (16.6 m), the University of Cambridge to work on epidemiological modelling on wheat and cassava diseases ($4.2m) and the John Innes Centre to test the feasibility cereal crops capable of fixing nitrogen ($9.8m). |

| Germany | 115 | Three grants for the German Federal Enterprise for International Cooperation (GIZ) to develop supply chains for African ca shews and for support to African rice farmers ($51.1m), and another three grants for the German Investment Corporation to work on African cotton and coffee farming ($48.8m), amongst others. |

| Netherlands | 61 | Mostly for two grants to the Wageningen University for agronomic research on grain legumes ($47.8m) |

| India | 41 | Total of ten grants including two grants to PRADAN ($30.8m for women farmers training), and to BAIF ($6.3 m. for establishment of cattle development centres) |

| China | 37 | Mostly for the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (two grants totalling $33 million) to develop new rice varieties for farmers across the world. |

| South Africa | 37 | 14 grants to a variety of grantees, including the FANRPANnetwork to carry out agriculture programmes ($16m), University of Pretoria ($4.5m for policy research) Sangonet ($1.7m. for mobile phone applications for farmers), SACAU (two grants $5.8m to support farmers organisations and electronic farmer management systems, and the Association of African Business Schools ($1.5m to develop agribusiness management and training programmes). |

| Uganda | 36 | Mostly for RUFORUM (two grants totalling over $30 million to support agricultural research universities in the region). RUFORUM was established as a programme of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1992 and became an independent Regional University Forum in 2004. |

| Australia | 30 | A total of 14 grants mostly to universities and research centres to develop sorghum and cowpea hybrids for Africa and other sorghum breeding programmes, deliver solutions to dairy cattle genetics in poor countries, and supply cattle genotypes to dairy farmers in East Africa, amongst others. |

| Canada | 20 | A total of 8 grants mostly to universities to ensure adoption of new technologies, develop cassava seed supply chains in Tanzania, and radio programmes in Africa, amongst others. |

| Total top 10 | 1413 | $1.4 billion, or almost half of all agriculture funding from Gates in the last decade went to grantees in these 10 countries: 90% to the North. |

Notes

1 Gates Foundation website, “Agricultural Development, strategic overview”.

2 Gates Foundation website, Foundation Fact Sheet.

3 We used the grants database on the Gates Foundation website and analysed the grants listed under ‘Agricultural Development’, 610 grants totalling US$ 3,110,591,382. (Database last accessed on 7 October 2014: http://tinyurl.com/m9s42z7).

4 Download the database as an Excel spreadsheet or as a more printer-friendly table (44 pages).

5 For a discussion on Gates and the CGIAR, see: SciDevNet, “Are Gates and CGIAR a good mix for Africa?”, 2010.

6 Several good critiques on AGRA already exist and we won’t repeat them here. See, for example, African Centre for Biosafety, “AGRA: laying the groundwork for the commercialisation of African agriculture” , by Food First, “Out of AGRA: the Green Revolution returns to Africa” (2008), GRAIN, “A new Green Revolution for Africa?” (2007) and others.

7 From the Gates Foundation’s Agricultural Development Strategy 2008-2011, quoted in Phil Bereano and Travis English, “Looking in a gift horse’s mouth”, in: Third World Resurgence, TWN, Penang, 2010.

8 On the Policy Action Nodes, see: AGRA 2013 Annual Report. For info about the Ghana Food Sovereignty Network: http://foodsovereigntyghana.org/

9 Most of these activities are carried out by the Open Forum on Agricultural Biotechnology in Africa (OFAB), created by AATF in 2006 to achieve “increased adoption of GM products in Africa and the rest of the world” See: http://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/partners

10 Gates Foundation website, “Agricultural Development, strategic overview”.

11 Figures based on the foundation’s 2012 tax returns, as reported in Alex Park and Laeah Leet, “The Gates Foundation’s hypocritical investments”, Mother Jones, 6 December 2013.

12 Charles Piller, Edmund Sanders and Robyn Dixon, “Dark cloud over good works of Gates Foundation”, Los Angeles Times, 7 January 2007.

13 Gates Foundation website, “Our investment policy”

14 Figures based on the foundation’s 2012 tax returns, as reported in Park and Leet, “The Gates Foundation’s hypocritical investments”, Mother Jones, 6 December 2013.

15 John Vidal, “Why is the Gates foundation investing in GM giant Monsanto?” Guardian, 29 September 2010.