How African Slavery Civilized Britain

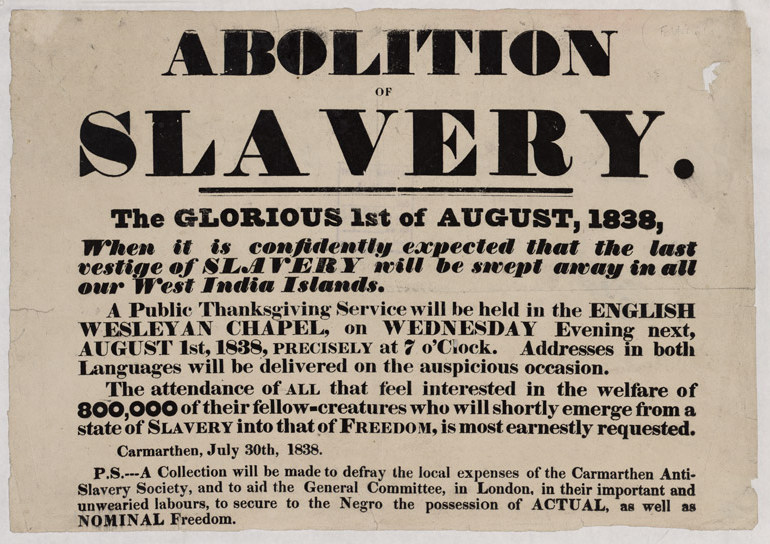

Friday marks the anniversary of the Parliamentary abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. Over the course of three centuries, Britain became the largest slaving nation in the world and the slave trade grew to become Britain’s largest and most profitable industry. Britain generated an estimated equivalent of four trillion pounds on the unpaid labour of slaves.

Britain owes its very existence as a first world nation to the African slave trade. Great Britain’s economic way of life was formed by slavery: about it revolved, and on it depended, most of Britain’s other industries.

Fathers became ostentatiously wealthy constructing slave ships or owning huge plantations in the Caribbean; when they died, their sons inherited that wealth and chartered banks that have endured to this day such as Barclays Bank, they built factories, British railroad enterprises, invested in government securities, and speculated in new financial instruments. In due course, they donated their slave profits to build libraries, museums, botanical gardens, and British universities.

Slavery did not only build Britain, it civilized her.

At the height of the British Empire, London was the cultural and economic capital of the world, and today London remains one of the world’s wealthiest and most influential cities.

However, before the British slave trade began in the 1500s, over 90 percent of medieval London’s population was illiterate and the city had largely forgotten the technical advances of the Romans some 900 hundred years before. There were no street lamps or paved streets in London and garbage and human waste were simply thrown into the streets.

Between 1348 and 1665, there were 16 outbreaks of the plague in London, at times killing almost half of the city’s inhabitants. Most houses were made of wood, mud and dung. All of this occurred at a time when the great empires of the world were Black African empires, and the educational and cultural centers of the world were predominately African.

Whilst Europe was experiencing its Dark Age, which was a long period of intellectual, economic and cultural backwardness, Africans were experiencing an almost continent-wide renaissance. The leading civilizations of this African rebirth were the Benin Empire, Kingdom of Ghana and the Mali Empires.

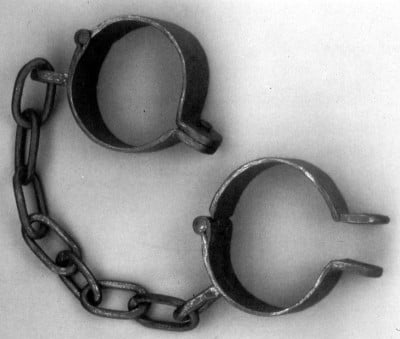

Between the early 1500s and the early 1800s, millions of slaves were kidnapped from Ghana, Mali and accross West Africa. By the mid-18th century, Britain was the biggest slaving nation, and Britain’s major ports, cities and canals were built on invested slave money.

Beyond any doubt it was the slave trade that raised London from an uncivilized medieval city to be the richest and most prosperous city in the world.

Slavery was integral to Great Britain’s economy from the Royal family to the Church of England on downwards. Britain’s slavers were defended before god by the Archbishop of Canterbury, and before parliament by politicians, like William Gladstone, himself the son of a wealthy plantation-owner.

In his famous 1944 book Capitalism and Slavery, the Trinidadian scholar Eric Williams illustrates how profits from slavery “fertilised” many branches of London’s economy and spurred England’s industrial revolution.

The processing and distribution of produce such as tobacco, sugar and cotton produced on plantations resulted in massive investment in British quaysides, warehouses, factories, trading houses and banks. Banking is currently Britain’s biggest industry and apart from the Barclays Brothers, who were slave traders, we also know of Barings and HSBC, which can be traced back to slaver Thomas Leyland’s banking house. The Bank of England’s founding is also inextricably linked to slave profits. Sir Richard Neave, who was the director of the bank for half a century, was also the chairman of the plunderous Society of West India Merchants.

British historian Robert Blackburn calculates that in 1770, total investments in the domestic British economy stood at £4 million, (or about £500 million in today’s money). This investment included the building of roads and canals, of wharves and harbours, of all new equipment needed by farmers and manufacturers, and of all the new ships sold to merchants in a period of one year.

Around the same time, British slave-based plantation and commercial profits came to £3.8 million (or about £450 million in contemporary terms). Clearly, slave based profits were so significant that they literally bankrolled Britain’s development and ascent into a first world nation.

The modern civilized world owes its very existence to the most uncivilized institution of slavery. In fact, slavery is not a product of Western civilization; Western civilization is a product of slavery. By fuelling the industrial revolution and propelling the mercantile expansion of the British Empire, slavery built the foundations of modern British civilization.

Throughout the ages monuments have epitomized and defined civilizations. Slavery had a profound impact on the development of British architecture from the great many monuments and statues across London, which celebrate Britain’s deep involvement in transatlantic slavery to the construction of countless ostentatious country houses.

Famous London landmarks and areas are also deeply intertwined with slavery. For instance, Sir Hans Sloane, whose statue stands in Sloane Square, was a principle shareholder of the plunderous Royal Africa Company, whose sigil was an Elephant and Castle, which gave its name to an area in south London. Sloane was also the President of the Royal Society and founder of the British Museum.

Museums are a quintessential symbol of modern civilization. Prior to the era of British slavery, museums tended to be small and private, open only to the aristocracy of a given nation. During the height of British slavery in the 19th century, the modern museum as we know it began to take shape. With plunder streaming in from all corners of the British Empire, the modern museum was born. The British Museum was created largely as a repository for artifacts looted from Africa between the 17th and 19th centuries.

Arguably the greatest contribution that slavery made to British civilization was how slaves freed up time for British slave owners and their families to engage in social activities and sustained experiments that led to inventions that propelled the industrial revolution. For instance, slavery financed the experiments of James Watt, inventor of the first really efficient steam engine.

Many historians agree that slavery was also crucial in developing British democracy, since it allowed men greater time for public participation.

Slave ships were also the principle reason for Britain’s explosion in medical advances. British slave ships were essentially floating laboratories, offering medical researchers a chance to examine the course of various diseases in somewhat controlled, quarantined environments. British doctors and researchers gleaned priceless epidemiological information on a range of diseases including malaria, smallpox, cholera, yellow fever, dysentery, typhoid, and so on, from the bodies of dying and dead slaves. Conditions on slave ships were so bad that, in his 1789 speech opening the parliamentary debate on the slave trade William Wilberforce estimated that half of the slaves, or six million souls, transported never made it to their destination.

As Professor Eric Williams explains, Britain ultimately abolished slavery, not for moral reasons, but simply because abolition was now more profitable than continuing sugar plantations. A century of sugar cane raising had exhausted the soil of the islands, and the plantations had become unprofitable. It became more profitable for British slave owners to simply sell the slaves to the government than to continue operations.

In 1833 the British Government paid slave-owners the equivalent of £17 billion in compensation, or roughly 40 percent of the national budget. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s cousin Sir James Duff was one of many British slave owners who received his share of billions of pounds for having had the privilege of exploiting slaves to enrich himself. The slaves themselves received nothing by way of compensation.

The Caricom group of Caribbean nations has recently put pressure on David Cameron for Britain to formally apologize for slavery and pay reparations. Mr. Cameron’s recent response before the Jamaican Parliament was to refuse to apologize and to tell Jamaicans to simply “move on”.

According to one estimate by Harpers Magazine, slaves between 1619 and 1865, when slavery was ended performed 222,505,049 hours of forced labor. Compounded at interest and calculated in today’s currency, this adds up to trillions of dollars. In fact, more riches flowed to Britain from the slave economy of Jamaica than all of the original American thirteen colonies combined. It is little wonder why David Cameron is keen to ignore any discussion with Jamaica about fair reparations.

Every year representatives of the German Finance Ministry and representatives of European Holocaust survivors meet to discuss reparations.

So far, Germany has paid $89 billion in compensation to Jewish victims of Nazi crimes. The Jewish claim to reparations is clearly just and so too is the Caribbean’s claim to slavery reparations. So one wonders if Mr. Cameron would tell Jewish victims not to accept reparations money and to simply “move on” as he told Jamaicans?

The racial hypocrisy of the British government is clear: European Jews deserve billions in compensation but Africans deserve not even an apology, despite modern British capitalist civilization owing its very existence to slavery.

Nations must not be defined merely by what they decide to remember, but more importantly by what they choose to forget. During slavery, ordinary Britons may not have known the brutal subtleties of how sugar lumps arrived at their tables, but people today must not forget how the brutality of slavery not only built the prosperous Great Britain that we know today, but also how it civilized her.

Garikai Chengu is a scholar at Harvard University. Contact him on [email protected]