Haiti “Open for Business”: Sourcing Slave Labor for U.S.-Based Companies

Is the Caracol Industrial Park Worth the Risk?

Last October, officials from the Haitian government and a number of foreign governments and institutions, who call themselves“friends of Haiti,” saw their dream become a reality. Finally, there was earthquake reconstruction progress worth celebrating with the inauguration of the giant Caracol Industrial Park (PIC), which, according to its backers, will someday host 20,000 or maybe even 65,000 jobs.

President Michel Martelly was there, as were Haitian and foreign diplomats, the Clinton power couple, millionaires and actors, all present to celebrate the government’s clarion call: “Haiti is open for business.”*

“We supported the Caracol Park because we knew it was going to be an extraordinary thing for the north,” then-Social Affairs Minister Josépha Raymond Gauthier told Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW). “The park will allow us to ‘decentralize’ the country and create a northern ‘pole.’ It will also give people jobs in an extraordinary way!”

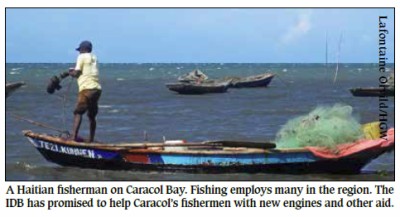

But a two-month investigation by HGW discovered that the number of jobs in the north is not yet “extraordinary,” and that many other promises have not yet been kept.

One year after it started operations, only 1,388 people work in the park; 26 of them are foreigners, and another 24 are security guards. Also, HGW research among a sampling of workers found that, at the end of the day, most have only 57 gourdes, or US$1.36, in hand after paying for transportation and food out of their 200 gourdes minimum wage (US$4.75) salary.

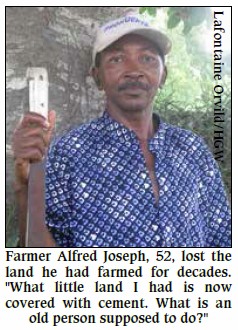

HGW also learned that most of the farmers kicked off the land to make way for the industrial park are still without land.

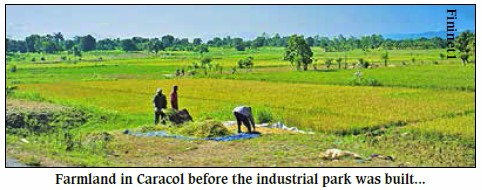

“Before, Caracol was the breadbasket of the Northeast department,” said Breüs Wilcien, one of the farmers expelled from the 250-hectare zone. “Right now there is a shortage of some products in the local markets. We are just sitting here in misery.”

Another farmer, Waldins Paul, a member of the Association of Caracol Workers, explained: “In my opinion, [the PIC] has its advantages and its disadvantages… The good part is that there are a lot of people who before didn’t have anything to do, who just sat around yawning. But now they see they aren’t getting that much for working, since 200 gourdes (about US$4.75) can’t do anything for anyone. What’s worse, it has impoverished the breadbasket of Haiti’s North and Northeast departments.”

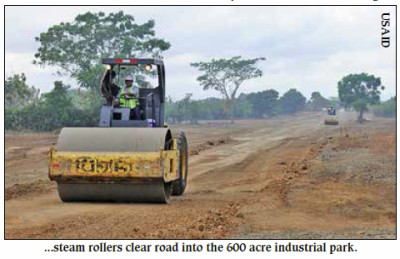

The PIC was put together by the U.S. and Haitian governments with help from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). It cost, for the first phase, at least US$250 million. Almost half, about US$120 million, came from U.S. citizens. Since then, more money has been spent on studies, roads, and on paying off the farmers expelled from their lands. [See “Caracol By The Numbers”]

“The disadvantages”

The January 2010 earthquake forcefully dislocated 1.3 million people in Léogâne and the capital. But those weren’t the only regions that saw dislocation. The PIC also forcefully expelled people: the 366 families who were farming 250 hectares of fertile land. [See “Haiti: Open for Business”to learn more about the choice of Caracol for the park.] The Chabert plantation assured the survival of about 2,500 people in those families, as well as 750 agricultural workers who toiled for at least 100 days per year each year on the plots.

The Haitian government requisitioned the land in November 2011, covered it with asphalt and fill, and put up giant hangers for the factories. The Technical and Execution Unit (Unité Technique d’Exécution – UTE), an agency of the Finance Ministry, has been charged with the task of relocating of the farmers, and also with paying them damages to cover the cost of every harvest lost until they receive new lands.

According to the UTE, each farmer is getting US$1,450 per hectare to make up for the lost cash revenue, as well as an additional US$1,000 per hectare to account for the food that the family would have eaten from its own plot(s). (HGW could not determine if the agricultural workers also received payments.)

In January 2013, the UTE told HGW that the state had paid out to the farmers on two occasions, because the farmers had lost two harvests thus far.

In addition to the money spent to reimburse the farmers – a total of about US$1.2 million, Haiti has also twice lost 1,400 metric tons (MT) of agricultural products, or 2,800 MT of food produced in Haiti for Haitian consumption. It takes over 100,000 bushels of dried beans to make up 2,800 MT. Finally, the UTE itself has an operating budget of about US$1 million. [See Caracol By The Numbers]

Verly Davilmar will be getting 35,000 gourdes, or about US$833, for the most recent harvest lost. Before, he worked a half-hectare of land, growing yams, manioc and spinach. No longer. No land. He sits at home. A family of 10.

“What they gave me is gone in a flash,” he told HGW. “There’s no other revenue. You don’t have any land so you have to make do with nothing.”

UTE Director Michael Delandsheer told HGW that his team has almost found a solution. The farmers will eventually get plots nearby, in Glaudine.

“Our first priority is to give the farmers land so they can work,” Delandsheer explained. “But even then, once they have land, we aren’t finished. We are going to make sure they get official leases to their land from the tax office, and we are going to accompany them throughout the process. Even then, our work isn’t done. We want to continue to accompany them, to help them improve their productivity.”

“Our first priority is to give the farmers land so they can work,” Delandsheer explained. “But even then, once they have land, we aren’t finished. We are going to make sure they get official leases to their land from the tax office, and we are going to accompany them throughout the process. Even then, our work isn’t done. We want to continue to accompany them, to help them improve their productivity.”

After almost two years of promises, the Caracol farmers remain skeptical. Some of the farmers in the Ouanaminthe area, home to the CODEVI industrial park, never got lands they were promised after being displaced almost a decade ago.

Caracol farmers were also allegedly promised jobs. “They said our family would be able to work [at the PIC], but so far we haven’t gotten any job offers,” Davilmar said.

The assistant mayor of Caracol is also disappointed. At the beginning, Vilsaint Joseph was not completely supportive of the park, but he kept an open mind, he said. And he is happy that the commune now has electricity, thanks to the power plant built by the U.S.. But people in Caracol haven’t gotten jobs.

“There are people who are about 32 years old, who went and got training, but they didn’t get a job because of the flood of young people in their twenties,” the mayor lamented. “I think that isn’t right. People spent three months getting trained up but then were told – ‘no work for you.’”

The decline in regional agricultural production is also a worry, he said, because before, “come harvest time, there would be truckloads of corn and beans for Port-au-Prince.”

Of a dozen farming families questioned by HGW, all of them said the payments were insufficient. Some said they could not afford to send all of their children to school.

“We are thinking of organizing a sit-in to demand that the authorities give us land so we can work,” Breüs Wilcien told HGW during a recent telephone interview.

Wilcien got 42,000 gourdes (US$1,000) but he said he can’t pay for his children’s schooling.

“My entire household is suffering,” he said. “Before, we always had our manioc field. When things were going badly, we went out there and pulled some up to make sweet bread or to just eat as is. We are really suffering these days.”

The “winners”

If the farmers and their families can be considered as “losers,” at least for the moment, the government and its partners say that those who got jobs are “winners” because they have employment. All of the documents concerning Haiti’s reconstruction talk about the need to “create” jobs and in this regard, the PIC is held up as the biggest “success” thus far.

HGW interviewed 15 workers, men and women, employed at the South Korean factory employing most of the PIC’s workers. This assembly factory – S & H Global – is a subsidiary of SAE-A Trading. It puts together clothing for some of the biggest U.S.-based companies, including JC Penny and WalMart.

All of the workers – most of them women, as in assembly factories the world over – confirmed that they received the minimum wage of 200 gourdes (US$4.75) per day. Among the workers questioned, 11 said that they spent on average 61 gourdes on transportation each day, and another 82 gourdes on the midday meal and a drink. That left only 57 gourdes or about US$1.36, for all the additional expenses: water, electricity, food for the family, clothing, school fees, etc. [See “Haiti: Open for Business”]

“I can’t live on this salary. It doesn’t do anything for me,” Annette** told HGW.

Before the PIC, this mother of 10 worked at the CODEVI industrial park in Ouanaminthe. She lives near the border town and gets up early every day to come to the PIC. Annette left her job for the new position in the hope that conditions would be better, she said. She was wrong.

“What I found is not worth if,” she explained, but she doesn’t know what else to do. Annette is in the same position as the thousands of Haitians who agree to work for a 200-gourde daily salary.

“What I found is not worth if,” she explained, but she doesn’t know what else to do. Annette is in the same position as the thousands of Haitians who agree to work for a 200-gourde daily salary.

Economist Frédérick Gérald Chéry believes that the Haitian government has a flawed approach to the minimum wage question, and that it has made a huge error in focusing on assembly factories where workers rarely earn more than that. In addition to not providing enough income for even a basic existence, the State University professor notes that a 200-gourde salary cannot contribute to the growth of other sectors of Haiti’s economy.

“You have to calculate what a worker earns and then what he can buy with that money,” Chéry told HGW during a November 2012 interview. “What he can buy is the most important factor. You should not set the minimum wage according to absolute terms, but in terms of the basic necessities. You should not encourage a worker to buy rice that comes from the U.S. or the Dominican Republic. A minimum wage should be able to buy local products.”

Waiting for a bus to go back home to Cap Haïtien, Flora* was overjoyed to talk to a journalist, despite clearly being exhausted.

“God sent you,” she said. “I have been needing a journalist to talk about what we are putting up with in the park. They yell at us as if we were animals. The food they prepare is bad. There is only warm water to drink. Sometimes I’ve had to work all day without a face-mask. Dust fills my nose.”

The workers’ comments were backed up by a recent report from “Better Work,” an agency of the UN’s International Labor Organization, which found that half of the 22 assembly factories in the capital region were “in non-compliance” as far as working conditions were concerned, and that 16 of them did not have an “acceptable” temperature.

Asked about salaries and working conditions at its Caracol factory, a representative of SAE-A contacted via email said the company respected all aspects of Haitian law. However, when HGW asked to visit the factory in order to see the working conditions, the request was denied. More recently, a union organizer also asked to visit the factory in order to see working conditions. That request was also denied.

HGW’s investigation revealed that of the 15 S & H Global workers questioned, 80% said they felt the salary level vs. the amount worked did not make sense.

“It’s not worth it!” Adeline* said. “The supervisors don’t respect us. They don’t see us as human beings. They hit us with pieces of cloth.”

Formerly a merchant, Adeline said she wants to go back to her old profession rather than continue to suffer.

Haiti’s former Social Affairs Minister told HGW that she realizes the minimum wage offers a low salary. But she immediately echoed the same justifications that all the factory owners and managers repeat.

“Someone working in an assembly industry [factory] isn’t going to get rich overnight,” ex-Minister Josépha Raymond Gauthier said in a November 2012 interview. “But someone who has no job at all has no hope.”

The Caracol mayor told HGW that he felt the same way last year. Now that he knows more about what he called “unacceptable” conditions and the low salary, he has changed his mind. The jobs are nothing short of “humiliation,” Vilsaint Joseph said.

The Haitian government has said that eventually it will provide free bus transportation to workers and has also promised that some of them will receive housing with subsidized mortgages. Part of the US$120 million pledged by the U.S. government is for a US$31 million development of 1,500 small homes called “EKAM” and located near the PIC. According to U.S. and IDB documents, the houses – costing US$23,510 each – will be for workers as well as displaced Caracol families considered “vulnerable” because they are headed by a woman or an elderly person.

However, because only 750 are funded at the moment, relatively few will benefit. [See also Caracol by the Numbers]

Worth the risk?

In all, for the installation of the park, the power station, EKAM, the payments to the farmers, and other expenses, the U.S. government, the IDB and the Haitian government have spent over US$250 million. But even with that investment, the eventual benefits to Haiti and to the Haitian state are not guaranteed.

All of the companies that set up shop in the PIC will get various tax breaks, meaning that little money will end up in the state coffers. Until the year 2020, the clothing assembly companies, like S & H Global, have additional privileges thanks to the U.S. “HELP” (Haiti Economic Lift Program) law. [See “Haiti: Open for Business”]

S & H Global does employ 1,388 people and has promised to employ another 1,300 by the end of the year. In addition, SAE-A is building a school and will subsidize its operation.

But to establish those jobs, SAE-A closed down a Guatemala factory, throwing 1,200 workers on the street. The company left Guatemala for Haiti because of Haiti’s low salaries and because of the HELP law, according toPrensa Libre. Once the HELP advantages expire in seven years, will SAE-A also leave Haiti?

Even with these meager results, the Haitian government and other actors say the PIC is a good “bet.” In one document, the IDB promises that it will set Haiti on “the path of economic growth.”

Speaking to the New York Times in 2012, the IDB’s country manager José Agustín Aguerre recognized that “[c]reating an exclusively garment maquiladora zone is something everyone — I wouldn’t say tries to avoid, but considers a last resort.” Still, he said, the PIC is “a good opportunity” even though the salaries are “low” and the jobs “unstable.”

“[Y]es, maybe tomorrow there will a better opportunity for firms elsewhere and they will just leave,” Aguerre added. “But everyone thought this was a risk worth taking.”

Economist Frédérick Gérald Chéry has a completely different analysis. Chéry notes that rushing to set up assembly industries, without a global plan, and without a national debate, is an error.

“Rather than seeing the textile industry as a temporary thing, they see it as a contributing sector to our economy, and it cannot be that, because the salaries are too low and because we don’t produce any of the inputs,” Chéry told HGW. “We don’t produce the cloth, we don’t do the design, and we don’t have an ‘economy of scale.’ I predict a catastrophe if we stay on this path.”

Also, the economist noted, prioritizing the PIC over agricultural production is very worrying. “If we don’t develop our agriculture in parallel with the clothing assembly industry, the farmers will be the losers,” he said.

The Caracol Industrial Park is not the first big project full of promises to set up shop in Haiti’s north. In 1927, U.S. capitalists established the Dauphin Plantation to grow sisal for the international market. By World War II, the plantation had taken over 10,000 hectares of land and was the biggest employer in the country. But tens of thousands of farmers lost their land to make way for the monoculture, and the entire region became dependent on the industry.

After the war and the invention of nylon, sisal’s price plummeted. The investors pulled out and eventually – in the 1980s – the plantation closed, bankrupt. Its traces can be seen today: ruined buildings and land made less fertile by years of sisal plants.

One of the Caracol farmers remembered the plantation. He knows what happened when the industry closed down. “Today, if you go visit Derac, Collette, and Phaeton, you’ll see,” he said. “If it weren’t for the UN blue helmets and the World Food Organization, those people would have died of hunger by now.”

* Reporters from Haiti Grassroots Watch and many other media were denied access because they were not on a list compiled by a private media consulting group called Wellcom Haiti, located in the capital.

** This is a fictional name. HGW decided to conceal the identity of the workers in order to protect them from repercussions.

Haiti Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of the Animation of Social Communication(SAKS), the Network of Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA), community radio stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media, and students from the Journalism Laboratory at the State University of Haiti.