HAITI: Independence Debt, Reparations for Slavery and Colonialism, and International “Aid”

On May 16 and 17, the London-based Pan-Afrikan Society Community Forum (PASCF) will address the European Parliament on the issue of reparations for slavery and colonialism.

Oxalando Efuntola-Smith, Executive Director of Communications of the PASCF, will make the case for reparations before the Parliament.

“We see the case of Haiti as central to the argument for reparations,” Omowale Ru Pert-em-Hru, PASCF’s Executive Director of Operations, told Haïti Liberté.

For their presentation before the European Parliament, the PASCF requsted supporting letters from other organizations in the UK and around the world.

Below we present the letters submitted by the Office of International Lawyers (BAI) and the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), as well as that from Haïti Liberté.

Right One of History’s Greatest Wrongs

Restitute Haiti’s Independence Debt

Haïti Liberté’s Statement for the European Parliament

In Support of Pan-Afrikan Society Community Forum (PASCF)

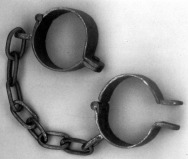

Haiti’s current economic crisis and political turmoil have their roots in the “odious debt” of 150 million gold francs (later reduced to 90 million) which France imposed on the newborn republic with gunboats in 1825.

The sum was supposed to compensate French planters for their losses of slaves and property during Haiti’s 1791-1804 revolution, which gave birth to the world’s first slavery-free, and hence truly free, republic. It is the only case in world history where the victor of a major war paid the loser reparations.

In fact, French colonial losses were only an estimated 100 million gold francs, if one stoops to placing monetary value on human slaves.

This extortion, perhaps more than any other 19th century agreement, laid bare the hypocrisy of France’s1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, modeled on the 1776 American Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed: “Men are born free and remain free and equal in rights.” The U.S., which assumed the debt in 1922, proved itself equally insincere in respecting this fundamental democratic principle for which it claims paternity.

It took Haiti 122 years, until 1947, to pay off both the original ransom to France and the tens of millions more in interest payments borrowed from French banks to meet the deadlines.

In 2003, Haiti became the world’s first former colony to demand reparations (in the form of debt restitution) from a former colonial power. Then President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s government conservatively calculated the value of the restitution due at some $21.7 billion. Although the French parliament had unanimously approved a law recognizing the slave trade as a crime against humanity in 2001, just two years later France responded to Haiti’s petition with fury. It angrily rejected the lawsuit and joined with Washington in brazenly fomenting a coup d’état against Aristide, who was ousted on Feb. 29, 2004.

For the past nine years since then, the U.S. and France have orchestrated the deployment of some 9,000 United Nations troops to militarily occupy Haiti, a mission which costs about $850 million annually. Known as MINUSTAH, the force has been responsible for massacres, rapes, and, most tragically, the October 2010 importation of cholera, which has now killed some 8,500 people and sickened close to 700,000 others. It is now the world’s worst cholera epidemic, and the UN refused in April to pay reparations to cholera victims who petitioned for it in November 2011.

Europeans and North Americans regularly dismiss demands for reparations, saying the crimes of slavery and colonialism were committed by their ancestors. If we accept the logic that responsibility for these crimes does not belong to the current generation, then we must also conclude that the great wealth reaped from those crimes – which facilitated Europe’s and North America’s primitive accumulation of capital and world dominance today – should also not belong to the descendants of slave-owners and colonists.

Why couldn’t and shouldn’t the billions now spent on policing, intimidating, and repressing the Haitian people be invested in the Haitian police, agriculture, education, and healthcare? This is what most Haitians ask today.

Europe should support, not the sending of UN troops, but the restitution for Haiti’s Independence Debt and just reparations for the crimes of slavery and colonialism. This would allow the Haitian people to rebuild their country as they see fit, not according to the blue-prints drawn up by multinational banks and foundations based in the former colonial and slave-owning nations. In short, restitution would allow self-determination.

Restitution of Haiti’s Independence Debt

Statement of the BAI and IJDH for the European Parliament

In Support of Pan-Afrikan Society Community Forum (PASCF)

The restitution of the independence debt imposed on Haiti by France in 1825 is the one fair and lasting solution to Haiti’s grinding poverty. The debt dwarfs current aid commitments and its payment would allow Haitians to develop their economy without the attached strings that keep poor countries dependent on international aid.

Haiti won its independence from France in 1804, through a bloody 12-year war, becoming the second independent country in the Americas and the only nation in history born of a successful slave revolt. But world powers forced Haiti to pay a second price for entrance into the international community. They refused to recognize Haiti’s independence, while French warships remained off its coasts, threatening to invade and reinstitute slavery.

After 21 years of resisting, Haiti capitulated to France‘s terms: in exchange for diplomatic recognition, Haiti’s government agreed to compensate French plantation owners for their loss of “property,” including the freed slaves; compensation to be paid with a loan from a designated French bank. The debt was ten times Haiti‘s total 1825 revenue and twice what the United States paid France in 1803 for the Louisiana Purchase, which contained seventy-four times more land.

The debt was a crushing burden on Haiti’s economy. The government was forced to redirect all economic activity to repay it. A huge percentage of government revenues—80 percent in some years—went to debt service, at the expense of investment in education, healthcare and infrastructure. The tax code and other laws channeled private and public enterprise to export crops such as tropical hardwoods and sugar which brought in foreign currency for the bank but left the mountainsides barren, the soil depleted and the population hungry.

Haiti did not pay off the independence debt until 1947. Over a century after the global slave trade was eliminated as the evil it was, Haitians were still paying their ancestors’ masters for their freedom. After the debt was paid, Haitians were left with a chronically undeveloped economy, rampant poverty, and a spent land — today relatively minor environmental stresses like tropical storms cause catastrophic damage in vulnerable Haiti.

Economic instability has engendered political instability. Haitians have endured more than 30 coups since 1825, and most of the resulting rulers have been malignant dictatorships. It has also engendered outsized vulnerability to natural disasters, as Haiti’s January 2010 earthquake demonstrated.

The independence debt was not only immoral and onerous, it was also illegal. In 1825 aggression and oppression did not violate international law, but the reintroduction of slavery — the threat underlying the debt agreement — did. It had been banned by three treaties that France had signed by 1815.

If the international community really wants to help Haiti, repayment of the independence debt will be at the top of the agenda, not off the table. A just repayment of the independence debt, by contrast, would allow Haiti to develop the way today’s wealthy countries did — based on national priorities set inside the country. It would also right a historical wrong, and set a strong example of a powerful country respecting the rule of law with respect to a less powerful country.

Sincerely,

Mario Joseph, Av.

Managing Attorney

Bureau des Avocats Internationaux

Brian Concannon Jr., Esq.

Director

Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti