Haiti: Drones and Slavery

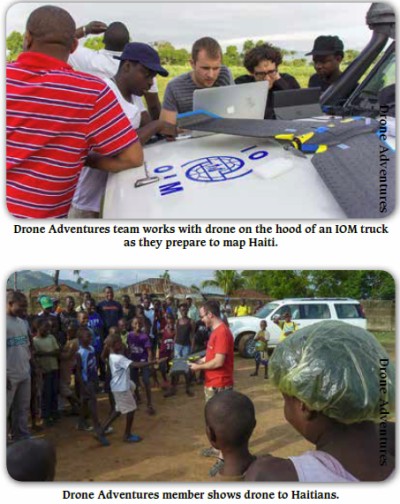

DroneAdventures.org is a Swiss “non-profit” organization that in April 2013 sent two representatives to Haiti to work with a couple of “non-profits” called Open Street Map and International Organization for Migration. For six days with three drones and several lap-top computers these “drone adventurers” mapped 1) shanty towns in Port au Prince to count the number of tents as a first step in making a census and organizing “infrastructure,” 2) river beds to simulate water flow for future flood control, and 3) the University of Limonade “to help promote the school for the next generation of youth in Haiti.”

DroneAdventures.org is a Swiss “non-profit” organization that in April 2013 sent two representatives to Haiti to work with a couple of “non-profits” called Open Street Map and International Organization for Migration. For six days with three drones and several lap-top computers these “drone adventurers” mapped 1) shanty towns in Port au Prince to count the number of tents as a first step in making a census and organizing “infrastructure,” 2) river beds to simulate water flow for future flood control, and 3) the University of Limonade “to help promote the school for the next generation of youth in Haiti.”

These drone promoters also made a cheerful video with a happy sound track, pretty pictures of the blue sky, and scores of children running after these pied pipers launching their falcon-like drones as if the children too could fly as easily out of the man-made disasters of life.

“Have you ever wondered how important it is to have detailed and up-to-date maps of a territory?” the drone promoters ask. Not only do we know they are important, we know enough to view them with suspicion. Historically, cartography developed in Europe for military, commercial, and exploitive purposes. “There is a continuous need for up-to-date imagery for aid distribution, reconstruction, disaster mitigation … the list goes on.” Indeed the list does go on, directly to bombing. These things are not for our own good, though every effort is made to start out that way.

The map depends on the bird’s-eye view, or the perspective from above. This viewpoint gave not only amusement but the illusion of omniscience which heretofore in European history had been reserved exclusively to the European divinities. The bird’s-eye view also inspired the Romantic movement of Europe. The viewpoint keeps us gaping upwards into the sky, and ignoring everything around us. The viewpoint initiates the class analysis and profound vision of Volney’s Ruins (1792) and Shelley’s Queen Mab (1812).

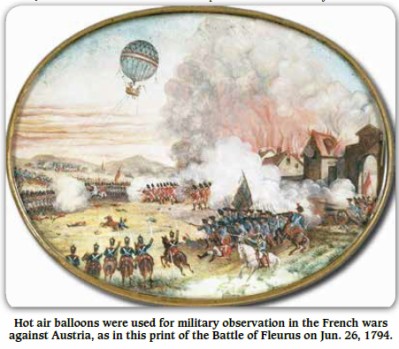

We have seen something like this before, with the origin of the bird’s-eye view. Consider the great French philosopher, Condorcet, or consider the brilliant American bourgeois, Benjamin Franklin. They both welcomed the first hot-air balloons on 11 September 1783 (oh, date of terror and dread!) which made the viewpoint possible. They noted the combination of present amusement and potential power of the balloon. A decade later the balloons were manned for military observation in the French wars against Austria. They are the ancestors of the dirigible, the airplane, (the bomber and the fighter), the rocket, and now the drone. The “bird’s-eye view,” and the aerial machines it makes possible, led directly to Guernica and Hiroshima.

We have seen something like this before, with the origin of the bird’s-eye view. Consider the great French philosopher, Condorcet, or consider the brilliant American bourgeois, Benjamin Franklin. They both welcomed the first hot-air balloons on 11 September 1783 (oh, date of terror and dread!) which made the viewpoint possible. They noted the combination of present amusement and potential power of the balloon. A decade later the balloons were manned for military observation in the French wars against Austria. They are the ancestors of the dirigible, the airplane, (the bomber and the fighter), the rocket, and now the drone. The “bird’s-eye view,” and the aerial machines it makes possible, led directly to Guernica and Hiroshima.

Horace Walpole, the English novelist wrote in 1783 as the first balloon ominously ascended over the countryside, “the wicked wit of man always studies to apply the results of talents to enslaving, destroying, or cheating his fellow creatures.” We could not express the essential contradiction better: technology and slavery went hand in hand.

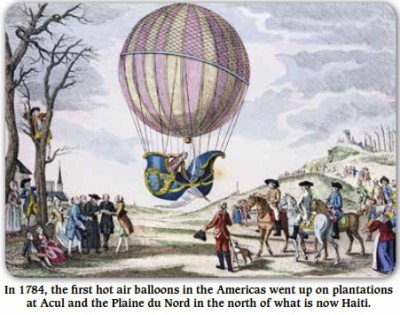

Within a year in Haiti, the first balloons went up on the Gallifet plantations at Acul and the Plaine du Nord. Here 800 slaves producing riches for Europe were managed by Odelucq, the man responsible for the balloon launch, indeed the first flight in America. What did the slaves think? Did they stare up into the blue sky with wide eyes and gaping mouths? Moreau, the contemporary scholar, provides the answer, “black spectators did not allow themselves to cry out over the insatiable passion of man to submit nature to his power.”

Within a year in Haiti, the first balloons went up on the Gallifet plantations at Acul and the Plaine du Nord. Here 800 slaves producing riches for Europe were managed by Odelucq, the man responsible for the balloon launch, indeed the first flight in America. What did the slaves think? Did they stare up into the blue sky with wide eyes and gaping mouths? Moreau, the contemporary scholar, provides the answer, “black spectators did not allow themselves to cry out over the insatiable passion of man to submit nature to his power.”

“The wicked wit of man” belonged to the European bourgeoisie not the black spectators. “How can we make a lot of sugar when we work only 16 hours [a day]?” asked Odelucq. Only by consuming men and animals, he answered himself.

The men and women would not be consumed so easily. They taught the children not to run after false gods or to Europeans preaching technological salvation. The spiritual, military, and social leaders of the slaves appealed to African sky-gods who answered with thunder and lightening on the historic night of 23 August 1791 in the Bois Caïman, thus initiating the first successful slave revolt in the history of the world. It began on the same plantations which had been Odelucq’s proving grounds. The sky above Le Cap turned dark with the smoke of burning plantations. Odelucq was among the first of the oppressors to pay with his life. Surveillance was answered by sousveillance!

The drones which today indiscriminately kill men, women and children in Pakistan and Yemen appeared first in the history of the technology as children’s toys, not weapons. Beware, the cunning eye of the master class is on you!

Peter Linebaugh is a historian at the University of Toledo and the author of the forthcoming “Stop Thief: The Commons, Resistance and Enclosure.”