France: Seeking Old Mandate in Syria

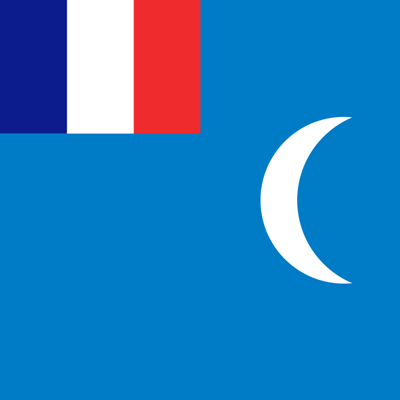

Russia’s decision to use its Air Force in Syria was a necessary step that is essential in order to maintain the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean. There is no alternative: Russia’s geopolitical interests dictate to block the Islamic State and other terrorist groups’ advance to the Mediterranean coast. This is not about messianism, although historically St. Petersburg, and later Moscow, have always been sensitive to stimuli coming from the Middle East. Meanwhile, the West is pulling out maps from the archives that date back to the French mandate for Syria and Lebanon (1923-1946). This means that not only the border between Syria and Lebanon is being questioned, but also the Turkish border as well.

Washington, London, Paris and Tel Aviv totally controlled the Syrian crisis – until July 14, 2015. After the Iran deal was signed in Vienna, Tehran then emerged at the forefront of a major game being played over gas supplies, and military activity intensified on the Lebanese-Syrian border. Paris and Tel Aviv saw this move as a challenge and carried out a series of air strikes over Syria in late September. When former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing offers his opinions, he speaks in the spirit of the colonial wars of the 19th century, urging UN forces headed by a French general to be sent to the Arab republic turning President Assad into only a nominal ruler, a dignitary who could be trotted out when needed to bless Paris’s restoration of that mandate. This is rapid progress. The historical figure of General Henri Gouraud leaps to mind, who in 1920 bested King Faisal I of Iraq (a member of the Hashemite dynasty) at the Battle of Maysalun, thus capturing Damascus. Gouraud was so ruthless in his conquest of the Arab Kingdom of Syria that in 1921 he was able to carve out from its vast territory the État de Damas, the État d’Alep, the Alawite State (known as the Sanjak of Latakia), Jabal al-Druze (the Druze State), the Sanjak of Alexandretta (present day İskenderun and the Hatay Province in southern Turkey), and also Greater Lebanon (1920). Those unifications endured, in various incarnations, until 1946, when Paris withdrew its troops under pressure from Arab nationalists.

From a geographical point of view, the French today are operating within their sphere of influence, which was formed as a result of the conference in San Remo in 1920. For this reason, the French air force launched attacks (on Sept. 27) on the oil-rich northeastern city of Deir ez-Zor, where back in 1921 they had set up a military garrison, which was incorporated into a unified Syria in 1946. The French colonial empire, which was buried in 1962 under the rubble of the uprising in Algeria, has not only survived in the minds of the political elite, but is also showing a determination to be reincarnated.

From a geographical point of view, the French today are operating within their sphere of influence, which was formed as a result of the conference in San Remo in 1920. For this reason, the French air force launched attacks (on Sept. 27) on the oil-rich northeastern city of Deir ez-Zor, where back in 1921 they had set up a military garrison, which was incorporated into a unified Syria in 1946. The French colonial empire, which was buried in 1962 under the rubble of the uprising in Algeria, has not only survived in the minds of the political elite, but is also showing a determination to be reincarnated.

The paradox is that Assad, an Alawite, is not requesting military assistance from Paris, which in the minds of Syrians is a symbol of dyed-in-the-wool European colonialism, but from Moscow. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, but the people of the Middle East have positive memories of Soviet presence in the region. In this sense, the air strikes carried out by the Russian air force on Jabhat al-Nusra & Daesh positions are marking the outlines of the absolutely new post-colonial framework for the Middle East, which was created not through secret diplomacy, but through the good will of Damascus and Moscow. It caused indignation of a vainglorious France. Yet everything is being done in a fully legal manner: Moscow’s actions are supported by a bilateral (with Damascus) Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Assistance. François Hollande cannot hide his resentment, and he is now accusing Assad of wholesale slaughter. And this is not empty rhetoric. Paris is trying to claim that this matter falls under the jurisdiction of 2005’s Resolution on theResponsibility to Protect (R2P), which obliges the UN Security Council to use force against regimes that allow “ethnic cleansing,” “genocide,” or “mass killings.” The French have not lost hope. After all, that gimmick worked with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

Russia’s stronger hand in the Middle East is a fact that has already been recognized by the US and Great Britain. Prime Minister David Cameron, who previously maintained an uncompromising position regarding Bashar al-Assad’s hold on power, is now saying the Syrian leader could play a role a “transitional government,” although in public he continues to threaten him with an international tribunal, working in sync with Hollande. The Guardian quoted Cameron as saying that “So far, the problem has been that Russia and Iran have not been able to contemplate the end state of Syria without Assad.”

The Israelis are in an uproar, especially after these words from Putin: “We respect Israel’s interests related to the Syrian civil war. But we are concerned about its attacks on Syria.” Translated from the language of diplomacy, this is a warning. Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon retorted, “Israel is not coordinating its operations in Syria with Russia.” He feels that the border between the Jewish state and the Arab Republic is the exclusive prerogative of Tel Aviv. The Kremlin is not contesting this position, which stems from the Israeli vision for the Middle East’s future borders (including Jabal al-Druze). The problem lies elsewhere. Without outside help, would Israel be prepared to survive a political earthquake in the Muslim world?

Sarkis Tsaturyan is the Russian-Armenian historian and international policy analyst. He teaches at the Moscow Peoples’ Friendship University.

Proclamation of the state of Greater Lebanon, Gouraud with Grand Mufti of Beirut Sheikh Mustafa Naja, and on his right is the Maronite Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek, Sept 1, 1920.

Source in Russian: Regnum, Adapted and translated by ORIENTAL REVIEW