Federal Judge Rules NSA Phone Data Collection is Legal and Justified by the 9/11 Attacks

A federal judge in New York City ruled that the National Security Agency (NSA) program that collects the telephone metadata for every call made in the United States and many of those made overseas is legal and constitutional. Judge William Pauley III ruled in favor of the Obama administration, dismissing a lawsuit against the NSA spying program brought by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The 53-page opinion issued Friday completely accepts the official rationale for the assumption of police state powers by the US government. It is all justified, Judge Pauley declares in his opening paragraphs, by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

These attacks succeeded “because conventional intelligence gathering could not detect diffuse filaments connecting al-Qaeda,” he claims. This is a slightly more flowery version of the long discredited claim that US government agencies failed to “connect the dots” before 9/11. This contention has been promoted by the intelligence agencies and echoed by the media to conceal the fact that many of the 9/11 hijackers were known to US intelligence agencies and at least some were under their direct surveillance in the months before the attacks.

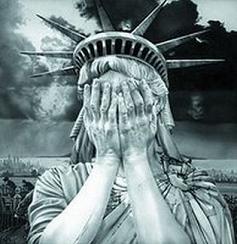

Pauley concedes that the NSA metadata collection is a threat to democratic rights. “This blunt tool only works because it collects everything,” he writes. “Such a program, if unchecked, imperils the civil liberties of every citizen.” He then spends the rest of the document arguing against any effort to impose such a check.

Now the third in seniority among judges in the Southern District of New York, Pauley was appointed by President Bill Clinton, a Democrat, to fill a traditionally Republican seat on the court. He was groomed by the Nassau County Republican Party machine and served as counsel to the Republican minority in the State Assembly for more than a dozen years. He is a reliable defender of corporate and Wall Street interests.

The judge’s ruling takes up three main legal questions: whether the ACLU plaintiffs have legal standing to bring the suit; their claim that the NSA metadata collection is illegal, exceeding the measures authorized by Congress under the Patriot Act; and their contention that the collection program is unconstitutional, violating the US Constitution’s Fourth Amendment prohibition of searches and seizures without a warrant issued by a court.

The ACLU suit, which names Director of National Intelligence James Clapper as principal defendant, was initially dismissed for lack of standing because the ACLU could not prove it had been targeted by the NSA metadata collection program. It could not provide direct evidence to that effect because the government insists everything about the program is secret, including the identity of those spied upon.

The situation changed with the release of documents by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, beginning last May and June. The ACLU re-filed its lawsuit, arguing that since the government had confirmed the existence of the metadata collection program—a decision made by the Obama administration to conceal even more intrusive programs—anyone who was a customer of the major telecommunications firms had standing to sue. Judge Pauley conceded that this argument was irrefutable and proceeded to the substance of the suit against the NSA spying.

The ruling is saturated with a pro-government bias. Pauley accepts unquestioningly even the most obviously bogus assertions by US military and intelligence agencies, while reserving his scorn and contempt for Edward Snowden, the whistleblower who exposed much of the police state apparatus, and the ACLU itself, the main plaintiff in the suit.

Thus Judge Pauley writes: “Bulk telephony metadata collection under FISA is subject to extensive oversight by all three branches of government,” citing high-level executive branch control of NSA spying, judicial review by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) court (which rules in secret on spy activities, after hearing only the government side of the case), and oversight by Congress (a reference to rubber-stamping by the House and Senate intelligence committees).

After a lengthy and somewhat technical argument that only a telephone carrier, not the user of the telephone, can legally challenge a NSA metadata collection order—and then only in the secret FISA court, not in a federal district court—Pauley lashes out in a passage that reveals the hatred of Edward Snowden in official circles.

“The ACLU would never have learned about the section 215 order authorizing collection of telephony metadata related to its telephone numbers but for the unauthorized disclosures by Edward Snowden,” he writes. “Congress did not intend that targets of section 215 orders would ever learn of them. And the statutory scheme also makes clear that Congress intended to preclude suits by targets even if they discovered section 215 orders implicating them. It cannot possibly be that lawbreaking conduct by a government contractor that reveals state secrets—including the means and methods of intelligence gathering—could frustrate Congress’ intent.”

Only towards the end of his ruling, and then very superficially, does Pauley address the central constitutional claim, that the NSA metadata collection program violates the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution.

Pauley relies on the 1979 Supreme Court decision in Smith v. Maryland, which dealt with a police-installed pen register device that took down all the phone numbers dialed from a suspect’s home. The high court ruled that since the phone subscriber was giving these numbers to the phone company (by the act of dialing them), he had no expectation of privacy.

This was a reactionary and anti-democratic decision at the time, but with a relatively narrow impact because of the comparatively primitive technology employed. To cite that precedent today, in a world where the NSA can collect billions of phone records in a single day, add them to a still more gargantuan database, and trace all the interconnections within that database, is a transparent effort to use a specious legal rationale to justify police state methods.

In a decision handed down two weeks ago, a federal district court judge in Washington DC, Richard Leon, came to the opposite conclusion. Ruling on a lawsuit brought by conservative Judicial Watch founder Larry Klayman, Leon found the Smith precedent to have been superseded by the expanded technological and data analysis capabilities now available to the NSA.

Describing the NSA program as Orwellian, Leon wrote, “I cannot imagine a more ‘indiscriminate’ and ‘arbitrary invasion’ than this systematic and high-tech collection and retention of personal data on virtually every citizen for purposes of querying and analyzing it without prior judicial approval… Surely, such a program infringes on ‘that degree of privacy’ that the Founders enshrined in the Fourth Amendment.”

Judge Pauley’s ruling cites the Klayman case only to emphasize that he did not find Leon’s decision persuasive. Pauley claims that Smith is still the controlling precedent and that the Supreme Court has forbidden lower courts to overturn it.

At several points in this portion of the opinion, Pauley sneers at the ACLU plaintiffs’ arguments. He admits in the opening section that, “such data can reveal a rich profile of every individual as well as a comprehensive record of people’s associations with one another.” But when the ACLU argues that allowing a government agency to accumulate such information is a clear threat to democratic rights, Pauley blandly accepts the NSA’s assurances of innocence, writing that “the Government repudiates any notion that it conducts the type of data mining the ACLU warns about in its parade of horribles.”

He accuses the ACLU of “a fundamental misapprehension about ownership of telephony metadata,” mocking its brief because it refers repeatedly to “plaintiffs’ call records.” Pauley declares, “Those records are created and maintained by the telecommunications provider, not the ACLU. Under the Constitution, that distinction is critical because when a person voluntarily conveys information to a third party, he forfeits his right to privacy in the information.”

Here the reactionary logic of the Smith decision is taken to its ultimate conclusion. What remains of privacy? The only thing that is private is something you tell or share with no one. Every spoken word, every thought communicated to anyone else, becomes the property of the government. This is the legal formula for a totalitarian state.

In his conclusion, Pauley returns to his basic presumption—that everything the government says about itself is to be believed. “There is no evidence that the Government has used any of the bulk telephony metadata it collected for any purpose other than investigating and disrupting terrorist attacks,” he baldly states.

The judge simply disregards the likelihood that the “absence of evidence” might have something to do with the blanket of secrecy over the entire process and the determination of government spies to conceal their own illegal and unconstitutional acts. Neither the telephone metadata collection, nor the dozens of even more intrusive and all-encompassing spying programs—many of which include the direct interception of the content of communications—would have been known to the people of America, or the world, without the courageous intervention of Edward Snowden.