Disappeared Students in Mexico: Human Rights Watch’s Biased Coverage and Double Standards

Compare and Contrast: Human Rights Watch on Mexico and Ecuador

HRW statements about Ecuador’s policing are out of proportion compared to their statements about the disappeared students in Mexico.

The following two headlines are from news releases by Human Rights Watch (HRW) about two incidents that took place in September:

1) Mexico: Delays, Cover-Up Mar Atrocities Response

2) Ecuador: Police Rampage at Protests

The headlines suggest very similar events are described, but that’s not the case at all.

In Mexico, police fired on student protesters, killing three, and then disappeared 43 others by handing them over to a gang. Those basic facts are not disputed by anyone. In Ecuador, the allegations are vastly less serious and far more contested. There were no deaths, but police are accused of beating protesters, some of whom HRW concedes were violent.

Mexico is a close US ally, so HRW instinctively pulled its punches with the national government, which HRW accuses of actions that only “mar” – i.e. impair the quality of– its response to the atrocity. But the government’s failure to produce the missing students (alive or dead) over a month after their “arrest” does not simply “mar” the response. It has raised reasonable suspicions that the entire Mexican establishment is complicit in the crime. As Spanish singer-songwriter Joan Manuel Serrat put it, “They need to demonstrate that they are not accomplices of this barbarism, and of other barbaric acts the country has been enduring; this is a great opportunity for Peña Nieto to show it.” The atrocity has sparked protests all over Mexico and a great deal of international attention.

Ecuador’s left wing government, under Rafael Correa, is a member of ALBA, an alliance of left of center governments that includes, among others, Venezuela and Cuba. HRW’s statement about the much less serious allegations against Ecuador’s police was four times longer than the statement about disappeared students in Mexico, who, according to state-directed gang members’ admissions, were killed and incinerated. HRW officials rushed to Ecuador in September, immediately after the protests, to carry out a “fact-finding mission”. In addition to describing claims made by several alleged victims, HRW accused Correa’s government of “harassing” the private media in ways that foster impunity for police brutality. HRW’s evidence for this last allegation is very weak. For example, a private TV station was obliged to broadcast a seven-minute government rebuttal to a show about the protests that had aired the previous day.

HRW’s statement about the atrocities in Mexico, in contrast, says absolutely nothing about the government’s media policies. Even a very lengthy report (from last year) that HRW cited in their statement said nothing about the Mexican media. However, HRW’s 2014 World Report summary for Mexico does, very briefly, list some facts that show why the media is an important part of Mexico’s human rights disaster: “At least 85 journalists were killed between 2000 and August 2013, and 20 more were disappeared between 2005 and April 2013… ”. HRW said that “Journalists are often driven to self-censorship by attacks carried out both by government officials and by criminal groups, while under-regulation of state advertising can also limit media freedom by giving the government disproportionate financial influence over media outlets.”

State advertising? What about private sector elites who own the Mexican media as well as advertise in it, who are closely allied with the state, and who may have a vested interest in maintaining the blood-drenched status quo? Alice Driver wrote in Aljazeera.

“When I interviewed Juarez journalist Julian Cardona in 2013 for a film about violence in the Mexican media, he argued: ‘The media can be understood as a company that makes tacit or under the table agreements with governments to control how newspapers cover such government entities. You don’t know who is behind the violence.’”

[Mexican President] Peña Nieto’s close ties with Televisa, the largest media company in Latin America, have been widely documented and even earned him the nickname the ‘Televisa candidate’ during the elections.”

Televisa alone has about 70 percent of the broadcast TV market. Almost all the rest of the market is held by TV Azteca. A study, done by researchers with the University of Texas, of Mexican TV coverage during the 2006 presidential election found significant bias in favor of two of the three major parties that lean farthest to the right – one of which is the PRI, the party of current President Peña Nieto. The study concluded “both Televisa and TV Azteca gave significantly more coverage to the winning candidate, Felipe Calderón [of PAN], than to his main rivals, Andrés Manuel López Obrador [formerly of PRD] and Roberto Madrazo [of PRI] . Also, the tone of the news coverage was clearly favorable for Calderón and Madrazo and markedly unfavorable for López Obrador.” In US Embassy cables published by Wikileaks, US officials privately stated in 2009 that “Analysts and PRI party leaders alike“ were telling them that (then candidate) Peña Nieto was “paying media outlets under the table for favorable news coverage.”

Alice Driver has claimed that

“To create confusion, the Pena Nieto administration has pursued the strategy of making splashy high profile narco arrests, and of blaming all criminal activity, including murders and disappearances, on the fact that everyone involved was part of the drug trafficking business. This approach makes victims responsible for the violence they suffer, and it is promoted in the media in a way that makes all victims become suspects.”

Driver’s claim appears quite plausible and well worth HRW’s time to investigate. At the very least, there are extremely good reasons to doubt that Mexico’s private media can be relied on to expose the national government’s complicity with atrocities.

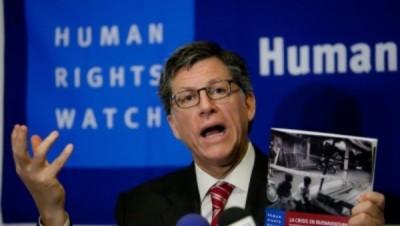

HRW’s 2014 World Report summary about Ecuador offers no evidence that Ecuadorian journalists are being murdered or disappeared under Correa (who has been in office since 2007) as their Mexican counterparts have been over the same period. But HRW nevertheless goes on at much greater length in critiquing Correa’s media policies. HRW’s critique is based on the assumption that private-sector elites pose no threat to freedom of expression or political diversity in the media. Any measure by a government – and especially left of center government like Correa’s – that clips the wings of private media barons is deplored. No positive suggestion is ever made by HRW for blunting the power of private media elites no matter how grave the human rights implications. It is this double standard that provides the basis of HRW executive director Ken Roth’s outrageous assertion that Ecuador and its ALBA partners—not U.S. allies such as Colombia, Honduras or Mexico—are “the most abusive” governments in Latin America.

In the case of the United States, HRW’s inability or unwillingness to identify the private media as major contributor, arguably the most important contributor, to its abysmal human rights record is truly farcical. There are striking examples, quite readily available as I mentioned here, of how the private media promotes a stunning level of ignorance about the scale of US government crimes, but HRW’s 2014 summary for the USA breezily asserts that the “United States has a vibrant civil society and media that enjoy strong constitutional protections”.

Then again, HRW is unwilling to even close its revolving door with US government officials, so the inability to challenge the way public and private power collude to stifle public debate in the USA, and in Mexico, is very unsurprising.