Did Wall Street Banks Create the Oil Crash?

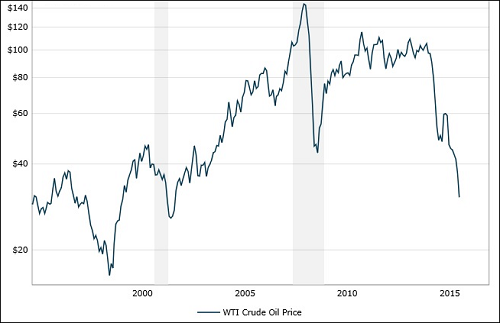

From June 2008 to the depth of the Wall Street financial crash in early 2009, U.S. domestic crude oil lost 70 percent of its value, falling from over $140 to the low $40s. But then a strange thing happened. Despite weak global economic growth, oil went back to over $100 by 2011 and traded between the $80s and a little over $100 until June 2014. Since then, it has plunged by 72 percent – a bigger crash than when Wall Street was collapsing.

The chart of crude oil has the distinct feel of a pump and dump scheme, a technique that Wall Street has turned into an art form in the past. Think limited partnerships priced at par on client statements as they disintegrated in price in the real world; rigged research leading to the dot.com bust and a $4 trillion stock wipeout; and the securitization of AAA-rated toxic waste creating the subprime mortgage meltdown that cratered the U.S. housing market along with century-old firms on Wall Street.

Pretty much everything that’s done on Wall Street is some variation of pump and dump. Here’s why we’re particularly suspicious of the oil price action.

Price of West Texas Intermediate Crude Oil Before and After the 2008 Crash

Americans know far too little about what was actually happening on Wall Street leading up to the crash of 2008. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission released its detailed final report in January 2011. But by July 2013, Senator Sherrod Brown, Chair of the Senate Banking Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection had learned that Wall Street banks had amassed unprecedented amounts of physical crude oil, metals and other commodity assets in the period leading up to the crash. This came as a complete shock to Congress despite endless hearings that had been held on the crash.

On July 23, 2013, Senator Brown opened a hearing on this opaque perversion of banking law, comparing today’s Wall Street banks to the Wall Street trusts that had a stranglehold on the country in the early 1900s. Senator Brown remarked:

There has been little public awareness of or debate about the massive expansion of our largest financial institutions into new areas of the economy. That is in part because regulators, our regulators, have been less than transparent about basic facts, about their regulatory philosophy, about their future plans in regards to these entities.

Most of the information that we have has been acquired by combing through company statements in SEC filings, news reports, and direct conversations with industry. It is also because these institutions are so complex, so dense, so opaque that they are impossible to fully understand. The six largest U.S. bank holding companies have 14,420 subsidiaries, only 19 of which are traditional banks.

Their physical commodities activities are not comprehensively or understandably reported. They are very deep within various subsidiaries, like their fixed-income currency and commodities units, Asset Management Divisions, and other business lines. Their specific activities are not transparent. They are not subject to transparency in any way. They are often buried in arcane regulatory filings.

Taxpayers have a right to know what is happening and to have a say in our financial system because taxpayers, as we know, are the ones who will be asked to rescue these mega banks yet again, possibly as a result of activities that are unrelated to banking.

The findings of this hearing were so troubling that the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations commenced an in-depth investigation. The Subcommittee, then chaired by Senator Carl Levin, held a two-day hearing on the matter in November 2014, which included a 400-page report of hair-raising findings.