Detroit Race Terror of 1863: Emancipation Proclamation and Draft Sparked Riots in the United States

Detroit City has been a center for the struggle against slavery and national oppression for a century-and-a-half

Historical developments in Detroit during early 1863 represented the social elements which have characterized race and power relationships in the United States since the Civil War.

During the course of the first two years of the War Between the States the southern Confederacy proved to be a formidable adversary of Washington. Many whites of all social classes rejected the notion of going to war to protect the Union particularly if the end result would be the emancipation of four million enslaved Africans.

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862 challenging the slaveholding secessionist states to end involuntary servitude by January 1, 1863. Two border states which did not secede, Missouri and Kentucky, were exempted along with Tennessee which was the last state to join the Confederacy and the first to return to the Union. Several other regions within some rebel states were also exempted as the political grip of the Confederacy had waned.

This executive order only served to enrage the Confederate planters even more along with prompting widespread opposition among Northern Democrats. The Democrats were the party of slavery and they controlled numerous newspapers in the North that maintained vociferous editorial positions against the Lincoln administration and the war. These Democrats who vehemently opposed the war to preserve the Union were called “copperheads” by Republicans supporting the war along with the Abolitionists.

On March 3, 1863, the U.S. Congress passed the Enrollment Act (Civil War Military Draft Act) mandating the conscription of men aged 20-45, both citizens and non-citizens seeking naturalization, into the military. Exemptions from the draft could be purchased for $300 and therefore the law targeted poor and working class whites who could not afford to buy their way out of serving in the Union military.

This new law resulted in the escalation of racial tensions against the African populations in the North. The Democratic Party press in New York City and other areas published articles and editorials designed to fuel hatred against African people.

These papers used the most derogatory slurs against African people as their standard editorial practice. They emphatically opposed the Conscription Act and encouraged defiance of the law.

New York historian Alan Singer wrote of the period that “In the months leading up to the July 1863 Draft Riots, John Mullaly, editor of the Roman Catholic Church’s newspaper, Metropolitan Record, called for armed resistance. At a Union Square rally May 19, 1863, Mullaly declared ‘the war to be wicked, cruel and unnecessary, and carried on solely to benefit the [n]egroes, and advised resistance to conscription if ever the attempt should be made to enforce the law.’ Following the July Draft riots, Mullaly was indicted for ‘inciting resistance to the draft.’” (historynewsnetwork.org)

The New York Draft Riots of 1863 pitted Irish immigrants against Africans residing in the city resulting in the reported deaths of over 1,000 people, mainly Blacks. Homes, businesses and orphanages were burned to the ground while local police and military forces in many cases sided with the racists.

This same author continues noting “The 1864 Presidential election provided the Copperhead press an opportunity to express open, casual, and nasty racism. A key figure was journalist David Goodman Croly, who at one time or another worked for the New York Evening Post, the Herald, and the World. Croly helped to anonymously produce one of the more avowedly racist attacks on Republicans and African Americans produced during the Civil War, a 72-page pamphlet titled ‘Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the White Man and the Negro.’ The pamphlet charged that the Civil War was a war of ‘amalgamation’ with the goal of ‘blending of the white and black,’ starting with the intermixing of Negroes and Irish.”

Race Terror Strikes Detroit in March 1863

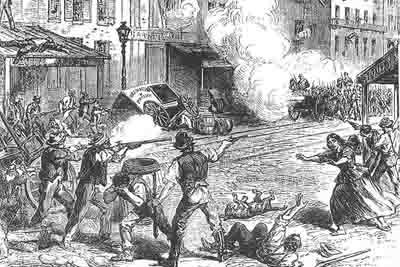

Four months prior to the New York Draft Riot on March 6, the African community in Detroit was attacked leaving at least two people dead and many others injured. The false charge of rape of a white girl was utilized to reign down violence on innocent residents of the city.

A tavern owner named William Faulkner was charged with sexual assault against two young girls, one white and the other Black on February 26. Faulkner’s arrest, trial and conviction was used a pretext to attack the African community where businesses and homes were ransacked and burned along with the beating, torture and outright murder of others.

Some accounts of the incident say that Faulkner had denied being of African descent that he was of Spanish and Native American descent. Others, including the Detroit Free Press, a Democratic publication and the Detroit Advertiser and Tribune, labelled him as Black, even if he only had a slightly distinct trace of African ancestry.

Racial tensions escalated in Detroit on the first day of the trial on March 5 when Faulkner was taken from City Hall to the jailhouse during which time he and his guards were attacked and hit with projectiles. After Faulkner was convicted on the second day, the Detroit Provost Guard mobilized to ostensibly protect the defendant while he was being moved back to the jail. The Guard fired shots in the air attempting to disperse the mobs but it did not work. Other shots were fired one of which struck a German man Charles Langer in the heart killing him.

The first building attacked belonged to a Black coppersmith and home owner, Whitney Reynolds, who was not at the location at the time. Nonetheless, the five people working in the shop were set upon by the white mob. Gunfire from inside the shop temporarily drove back the mob however soon enough the building was engulfed in flames forcing the inhabitants to flee. One man Joshua Boyd was struck in the head with an axe and died, becoming the second documented death of the day.

Crowds moved along Lafayette and Fort streets screaming “kill all the Niggers” while people attempted to defend their lives and property. Many of the copper shops owned by Africans were targeted with an obvious economic motive. Homes were torched with people in them while children, women and men were attacked without any pretense other than the color of their skin.

A document published anonymously in the aftermath of the terror campaign entitled “A THRILLING NARRATIVE FROM THE LIPS OF THE SUFFERERS OF THE LATE DETROIT RIOT,

MARCH 6, 1863, WITH THE HAIR BREADTH ESCAPES OF MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN,

AND DESTRUCTION OF COLORED MEN’S PROPERTY, NOT LESS THAN $15,000” provides first-hand accounts of the mob violence and the heroism of the African community. The text includes statements from various men and women who provide details on how the so-called riot began and proceeded within the city.

The U.S. military forces based at Fort Wayne and Ypsilanti were called in to put down the reign of terror. Order was said to have been restored by late that evening while the impact of the orgy of violence lasted for years to come.

Many Africans fled to Canada and areas in Michigan outside of Detroit. The Detroit Advertiser and Tribune labelled the incident as a “Free Press Riot”, attacking the newspaper for its pro-slavery position despite its editorial claim of supporting the Union against the succession by the Confederate states.

Faulkner spent seven years in prison at Jackson while the young white girl recanted her statements alleging sexual assault. This case was indicative of a racist judicial system that targeted Africans as a mechanism of social control and economic exploitation.

Historical Significance of the 1863 Race Terror

This important period in Detroit’s past helped set the stage for the Post Civil War racial and political construct. The utilization of sexual paranoia, economic exploitation and competition, a biased legal system, mob violence and forced removals characterized the treatment of African Americans through the latter decades of the 19th century and through most of the 20th century in the South, West and the North.

With the escalation in mass migration of African Americans into Detroit during World War I continuing through the 1960s, the city has been a boiling pot of racial unrest fueled by institutional discrimination and super-exploitation. The 1943 “Race Riot” and the 1967 Rebellion were also unprecedented episodes of conflict and state repression.

Today Detroit is facing a renewed round of political and economic policies designed to suppress the now majority African American population. If the history of the city since 1833 is any indication, the oppressed will continue their struggle for full equality and self-determination.

This report was delivered on February 24, 2016 at the Dr. Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Midtown Detroit.

The panel discussion entitled “Detroit: Attacked and Fighting Back” was sponsored by the Association for the Study of African American Life & History (ASALH), Detroit chapter. Also making contributions to the discussion was Sharon Sexton, a documentary filmmaker and historian; Dale Rich, photojournalists and historian; Orlin Jones, author and President of the Conant Gardens Homeowners Association in Detroit; and Nubia Polk of ASALH who served as moderator.