China’s Triangle Diplomacy

Back in the days of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, the “strategic triangle” with the Soviet Union and China was the great game. The idea was to play off the two communist powers against one another, relying on their ideological warfare under Mao, deep cultural differences, and open conflict in border regions to sustain their mutual suspicions and fears of attack. Now the shoe is on the other foot, so to speak: China seems to be in charge of the game, using US-Russia enmity and its own on-again, off-again competition with the US to keep both those countries cooperative with and in need of Beijing.

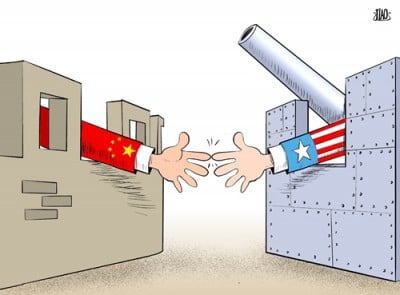

Obama said his meetings with Xi Jinping had given him the chance to debunk the notion that “our pivot to Asia is about containing China.” Xi said: “It’s natural that we don’t see eye to eye on every issue. But there have always been more common interests between China and the United States than the differences between us.” Indeed, although “strategic mistrust” defines the US-China relationship today, particularly when it comes to the “pivot” and US support of Japan’s position in the Diaoyudao-Senkaku islands territorial dispute, and despite Obama’s unresponsiveness to Xi’s call for “a new type of major power relationship,” the two countries have steered clear of strikingly antagonistic steps that would revitalize a cold war, or lead to hot war, in Asia. Take US-Taiwan military ties, for instance. The Obama administration has already sold Taiwan weapons valued at about twice as much as was sold under the G.W. Bush administration (about $12 billion). But since 2011, when Obama declined to sell F-16s to Taiwan, it hasn’t offered a new weapons package, much to the displeasure of both Taiwan and its supporters in Congress. Another example is the mild US response to the Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong. Obama said precious little on this sensitive matter, essentially giving China a pass to handle Hong Kong as it saw fit—precisely as Xi insisted. (“Hong Kong affairs are exclusively China’s internal affairs, and foreign countries should not interfere in those affairs in any form or fashion,” Xi told Obama in Beijing.) For its part, China has done nothing to obstruct US Middle East diplomacy and war making, has moved closer to the US critique of North Korea’s foreign policy, and has joined with the US in an historic agreement (albeit one based on promises, not performance) on climate change.

|

Besides climate change, the Obama-Xi meeting produced quite a number of other accords that are noteworthy. These are confidence-building measures to avoid potential air or naval confrontations, visa extension that will facilitate people-to-people exchanges, and broadening of trade in information technology. Needless to say, plenty of contentious issues remain unsettled besides the South China Sea territorial dispute, such as cyber hacking, human rights, and free-trade agreements in Asia. But on balance, the US-China agenda moved forward rather than backward as a result of the Obama-Xi meeting. (For further analysis, see David Shambaugh’s article.)

Another element in this “live and let live” moment in US-China relations is Xi’s renewed emphasis on soft power and promotion of China’s unique approach to international affairs. In a recent speech to a party work conference on foreign affairs, Xi proposed “six commitments” or “persistents” (liuge jianchi: 六个坚 持): peaceful coexistence, an end to great-power domination, opposition to the use of force and intervention, “win-win” approaches to international issues, aid to developing countries, and “never sacrificing the country’s core interests.”To be sure, these are standard Chinese foreign-policy themes of recent years. What is significant is that they are now presented as “China’s special characteristics for great-power foreign policy,” according to the foreign ministry. It is Xi’s way of proclaiming that China, far from accepting junior-partner status with the US in international affairs, has its own doctrine in the competition for regional and global influence. China’s forceful assertion of its interests in the South and East China Seas shows that it intends to back doctrine with power.

On the other side of the triangle, China and Russia appear to be moving ever closer. In May, Putin and Xi concluded a huge gas deal between their national oil companies—worth $400 billion over 30 years—as part of a large trade package. Russian gas that might have gone westward to Europe will instead be moving over about 2500 miles of pipeline to China. Their overall trade is climbing rapidly, and is expected to reach $100 billion by the end of 2014. Their militaries have carried out joint exercises, the two countries cooperate to combat ethnic “terrorists and separatists” on their common border, and they have compatible policies on North Korea, Iran, and Ukraine that run against US and European Union calls for escalating sanctions. As one astute observer, Gilbert Rozman, puts it, “Leaders in Moscow and Beijing want to avoid allowing chauvinistic nationalism in either country to trump their mutual national interest in minimizing the influence of the West in their respective regions”.

But appearances can be deceiving here: China and Russia have plenty of tensions that stem from past conflicts as well as present-day issues. China’s huge economic advantage over Russia, a dramatic change from the Soviet era, surely arouses Russian concerns. Russia’s interventions in its so-called near abroad, such as Georgia and Ukraine, may prompt Chinese memories of border clashes and Russian “great-power chauvinism” no matter what Beijing says publicly. And China’s notion of an Asian order doesn’t leave room for Russia except as a junior partner. On the Russian end, even though Putin is looking east for new trade deals, the fact remains that trade with the EU is worth more than five times as much as trade with China: $263 billion versus $59 billion in the first half of 2014.

In a word, notions of a new Sino-Russian entente that spells trouble for the US and its allies seem overblown. Beijing and Moscow are more united by what they oppose—namely, aggressive US foreign policy—than by a common agenda. Neither China nor Russia has powerful allies, so Xi and Putin mute their criticisms and trumpet their ties—two authoritarian regimes that are busy clamping down on domestic dissent. Nevertheless, as US conduct of the strategic triangle in Nixon’s time showed, diplomacy is almost inevitably uneven with respect to the two other sides of the triangle. Then, US relations with the USSR were far more important to Washington—but also more hostile—than relations with China. Today, China’s relations with the US are far more important to Beijing than relations with Russia, as evidenced by China’s deep regional and global involvement in the capitalist order, of which huge commercial and financial ties to the US are a major part.

Japan figures prominently in China’s triangular diplomacy. During the November summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Beijing, Xi Jinping met briefly with Abe Shinzo—a small breakthrough in China-Japan relations inasmuch as the Chinese had previously rejected such a meeting unless Japan acknowledged that their territorial dispute is in fact a dispute. Out of that meeting came a four-point agreement to promote mutual confidence and restore dialogue. () The two sides sidestepped the territorial dispute by acknowledging “different viewpoints” on the issue. More concretely, they agreed to set up a mechanism to avoid maritime conflicts in the East and South China Seas. China showed its reasonableness when dealing with a potentially dangerous situation—a confrontation with Japan at sea that has seen several close calls between vessels in recent years.

Xi probably welcomed Abe’s post-meeting comment that China and Japan “need each other” and are “inseparably bound together.” Since then, in a sign that high-level Sino-Japanese diplomacy has indeed resumed, a senior Japanese advisory group, the 21st Century Committee for China-Japan Friendship, visited Beijing on December 4 and met with two top officials, including Premier Li Keqiang. Full-fledged normalization of relations is still to come, however, as the Chinese repeated the position that the history issue is an obstacle the Japanese would have to overcome for relations to improve significantly.

Strategically for Beijing, the four-point agreement may be an effort to neutralize US expressions of support for Japan’s sovereignty over Diaoyudao/Senkaku. Beijing would like nothing better than to weaken Japan-US ties while Abe, a right-wing nationalist out to restore a prominent place for Japan in world affairs, is in power. And he will be, for another four years, thanks to an electoral victory December 14 for Abe’s Liberal Democrats. Despite his unpopularity, and the lowest level of voting in Japan’s postwar history (about 52 percent), the LDP will have 291 of 495 seats in the lower house of the Diet.

Economically, Beijing would no doubt like to see Japanese trade with and investment in China recover. In 2013, Japan’s trade with China fell by double digits for a second straight year, mainly because Japanese exports dropped by around 10 percent. Japanese investment in China showed the same two-year decline, falling in the first half of 2014 by nearly half of the comparable 2013 figure.

Meanwhile, Abe has several major domestic challenges now that the parliamentary elections are over. He needs to shore up the economy, now technically in recession, overcome opposition to restarting nuclear plants, and decide whether to pursue revision of the constitution’s Article 9 so as to legitimize the military’s participation in “collective defense” missions. He must also oversee what appears to be an officially sanctioned assault on liberal intellectuals and peace groups (see Jeff Kingston, “Extremists Flourish in Abe’s Japan,” Asia-Pacific Journal.) In short, Abe needs a period of calm in relations with China, not a confrontation. But if he uses his electoral victory to push a neonationalist agenda, the calm will not last.

Abe’s economic woes remind us that the foreign policies of states do not take place in a vacuum. Domestic problems invariably complicate and to some extent shape what national leaders do, or attempt to do, abroad. Right now, China’s leaders are dealing with a slowing of the economy, notwithstanding over 7 percent GDP growth. Xi is cracking down on dissent; a growing number of journalists, lawyers, prominent members of Uighur and other ethnic minority groups, and intellectuals are being jailed for supposedly subversive activities, with no promise of a quick, much less fair, trial. Official corruption is also a Xi target as he seeks, but not very credibly, to pose as a champion of justice by making an example of a few high-profile party officials and former officials. In Russia, Putin’s bravado is popular, but the economy is in freefall, in part due to EU and US sanctions. The US economic picture looks strong in comparison to these others, but Obama faces a rocky two years of divided government and constant political battles.

What all these problems add up to is the enduring lesson that leaderships need to spend time and resources dealing with the home front, which often constrains what they can accomplish abroad. China, Russia, Japan, and especially the US will have to tread more carefully abroad, avoiding confrontations with each other. That picture may help explain why China is now conducting triangular diplomacy with a “softer” touch, particularly when it comes to the United States and Japan. How long that will last is another matter.

Mel Gurtov is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University, Oregon, Editor-in-Chief of Asian Perspective, and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. His most recent book is Will This Be China’s Century? A Skeptic’s View (Lynne Rienner Publishers).