China-South Korea Relations: “Xi Jinping Visits Seoul: The Bigger Picture”

China and Korea watchers jumped to attention when it was announced that Xi Jinping would visit South Korea from July 3-4, rather than visit North Korea first. Although the trip could have been seen as reciprocating ROK President Park Geun-hye’s visit to China in June 2013, the Chinese side surely was aware that the trip would be viewed abroad as a departure from standard Chinese protocol and would probably upset Kim Jong-un and his colleagues. But while the trip can be judged a success for China, the North Koreans may have less to worry about than might at first appear.

As I see it, Xi had three aims. First, at a time when the United States has reemphasized its Asian alliances and particularly relations with Japan, Xi may have wanted to show the South Koreans that they also have a reliable friend in Beijing, one with more to offer economically than Japan. Second, Xi wanted to demonstrate the economic importance of Republic of Korea (ROK)-PRC ties as the United States struggles to promote the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) idea. Third, he hoped to generate interest in resuming dialogue with North and South Korea on denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

China is out to gain acceptance of a foreign-policy concept that will distinguish it from the US alliance system, which Beijing has always seen as a remnant of the Cold War. Currying favor with South Korea is an important starting point inasmuch as both countries’ relations with Japan are at a low point, effectively frozen in terms of summit-level diplomacy and tense because of territorial and historical memory disputes. Japan under Abe Shinzo is redefining its national security perspective in ways that neither Beijing nor Seoul finds acceptable—a reinterpretation of Japan’s peace constitution so as to permit involvement in “collective defense” missions, which now or later could mean direct support of US military action in East Asia or beyond and certainly goes hand in hand with the boosting of Tokyo’s base and military posture in the standoff with China in the East China Sea. Should China’s disputes with Japan escalate further, such as over Diaoyudao/Senkaku islands, Beijing would hope to have Seoul on its side or at least neutral.1 The same may go for South Korea in its dispute with Japan over Tokdo/Takeshima.

China-Republic of Korea (ROK) ties are already quite substantial, and represent remarkable growth since formal relations began in 1992. China now describes the relationship as a “strategic cooperative partnership” (战略合作伙伴关系). The two countries have established a multitude of bilateral mechanisms to govern cultural, political, and security affairs. China is South Korea’s number-one trade and investment partner, and China’s third-largest export market. Indeed, since 2010 South Korea-China trade relations have outstripped the combined total of China-US and China-Japan trade. Total ROK-PRC trade was over $270 billion in 2013 according to PRC statistics with a substantial trade balance in favor of the ROK. Meanwhile, the disputes with China have contributed to a sizable drop in Japan’s direct investment in China starting last year—a 4.3 percent decline, followed by a nearly 49 percent decline in the first half of this year.

A significant flow of people also demonstrates the growing importance of the China-South Korea relationship, with over 8 million travelers visiting each other’s country in 2013 and around 60,000 Chinese studying in South Korea—both topping Chinese rankings for tourism and study abroad.2

The commercial significance of Xi’s trip was indicated by the fact that he was accompanied by “over 250 Chinese entrepreneurs from manufacturing, finance and IT.” One specific agreement reached was on direct renminbi-won trading, eliminating the intermediary role of Hong Kong. Chinese accounts described South Korea as an “offshore center for the RMB,”3 meaning that the US dollar will not reign supreme in those countries’ transactions. The agreement is also relevant to a China-ROK free trade agreement (FTA), which the two sides have been negotiating for several years and say they are aiming to complete by the end of this year. Their FTA might be China’s biggest in Asia, a challenge to the US-backed TPP. South Korea’s trade ministry has indicated that while it intends to pursue participation in the TPP, which notably excludes China, it would prioritize the China-South Korea agreement.4 TPP negotiations have dragged on for four years, whereas bilateral free trade agreements, such as South Korea has with eight countries and regions, have been relatively easy to conclude. Neither country has an FTA with Japan.

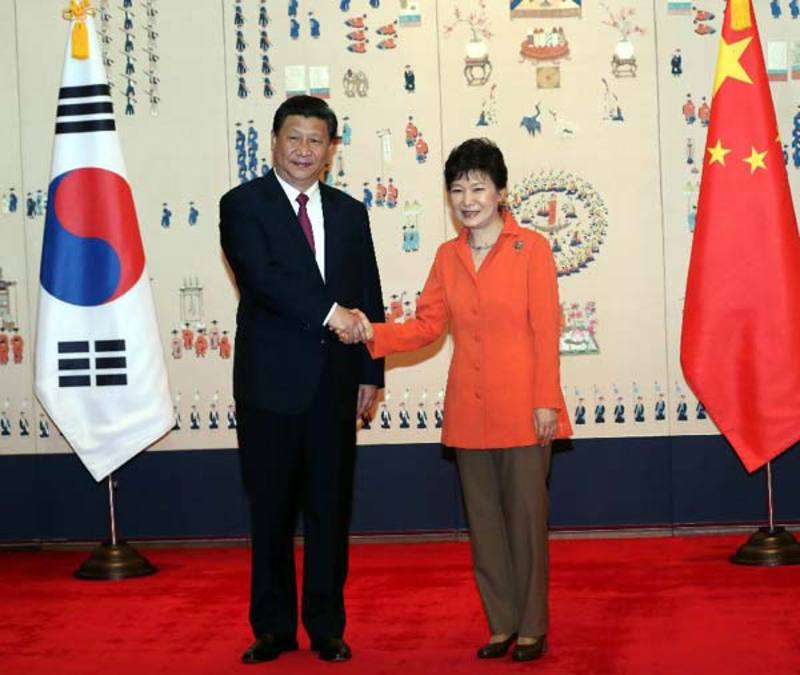

Xi and Park |

A number of commentators have suggested that Xi’s agenda was to erode ROK-US ties, but if so, the end result did not serve that purpose. ROK-US relations are very solid these days, all the more so in the defense arena, and President Park Geun-hye is not about to upset the apple cart in order to get closer to China. Notably, the final communiqué did not mention Japan; if it had, in a way that depicted Japan as a common adversary, Washington would surely have been miffed.5 But I don’t believe Xi’s objective was to undermine the ROK-US alliance. Judging from some Chinese commentaries, Beijing takes the alliance as a given, but finds close ties with South Korea useful in support of other Chinese objectives, such as avoidance of another Korean war, investment particularly in less-developed parts of China’s interior, and strengthening of the G20 group (of which the ROK is a member) as leverage against the G7.6 President Park surely finds these aims unobjectionable: As her administration sees it, a fulsome economic relationship with China and continuation of close security and other longstanding ties with the US are perfectly compatible.

A litmus test of Park’s policies toward the US and China may come with a final decision on participation in the US theater missile defense (TMD) system. Washington has been pushing the idea in South Korea for quite a few years, but up until now the South Koreans have preferred to upgrade their own ballistic missile defense, citing the cost and value for Korea of the US program. A Korea Times editorial opposing TMD participation observed that it would cost over $3 billion to acquire and operate the system, yet would have little practical value in deterring North Korean attacks and would antagonize China.7 The Koreans have also balked at US proposals for trilateral missile defense cooperation with Japan.8 The Chinese see TMD as a backdoor way for the US to neutralize China’s missile deterrent, and not merely as directed against North Korean missiles. If Park ultimately buys into it, as the Japanese have, this would provide a better gauge as to the effectiveness of Xi’s effort to wean the ROK away from the US. But that seems like a long shot unless Washington uses strong-arm tactics and makes South Korean adoption of TMD a condition of continued close military cooperation.

What President Park probably most wanted to hear from Xi was a strong commitment to pressing North Korea on nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles as a condition of resumption of diplomatic engagement. As is by now well known, discussion in Beijing has turned from consistent support of Pyongyang on the nuclear issue to concern about how Pyongyang’s behavior might hurt PRC interests. But China’s public position had already been established when Xi Jinping spoke in May to the 24-member Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building in Asia (CICA), a four year old Chinese diplomatic initiative.9 That group embraces most Asian as well as Middle East countries.

CICA 2014 plenary with Vladimir Putin (left) and Xi Jinping (center). |

The ROK is a member, but not North Korea; the US and Japan have observer status. Xi’s address mentioned China’s participation in the Six Party Talks, but did not list North Korea’s nuclear weapons among the specific Asian security issues he considered important. (He mentioned “terrorism, separatism, and extremism,” a region-wide code of conduct, and establishment of an emergency response center—notably staying away from the South China Sea and other contentious maritime issues) In Seoul, Xi would not go beyond what he and other PRC leaders have said many times: the Six Party Talks should resume, the September 19, 2005 Six Party joint statement on Korean issues should be fulfilled, dialogue should take place among all the parties at every level, and direct North-South Korea contacts should increase. Perhaps Xi was more forthcoming in private; but at least in the China-ROK final communiqué, Xi did not promise anything new concerning UN sanctions on North Korea or Chinese fuel or food deliveries to the North.

(Interestingly, North Korea released a statement on July 7 that called for renewed North-South Korean efforts to forge an agreement on national reunification. As in the past, the official statement insisted that “outsiders” not be permitted to interfere with Korea’s destiny. The statement made no reference to China-ROK relations, but it gives rise to speculation that the statement was in direct response to Xi’s visit. Conceivably, North Korea will now seek improvements in relations with both China and the ROK, though just recently Pyongyang’s official newspaper carried a strong criticism of “countries responsible for maintaining international justice [that] are remaining silent against the tyranny of the U.S.,” a reference to China’s refusal to object to UN Security Council condemnations of the latest North Korean missile tests.)10

For a larger perspective on Xi’s visit, we may want to refer back to his speech at the CICA. CICA’s charter contains principles that conform well to China’s five principles of peaceful coexistence (which Xi cited more than once) and a more recent “new security” formula: nonintervention, respect for sovereignty, peaceful settlement of disputes, and avoidance of use of force. What Xi has added, very much in keeping with prior statements, is the strong connection between development and security. “For most Asian countries,” he said, “development means the greatest security and the master key to regional security issues. . . . We need to advance the process of common development and regional integration, foster sound interactions and synchronized progress of regional economic cooperation and security cooperation, and promote sustainable security through sustainable development.”

China holds the conference chair until 2016, and Xi used it to provide a platform for introducing his regional security formula. Like Chinese leaders before him, Xi proposed a model alternative to the US-based spokes-and-wheel system. “One cannot live in the 21st century with the outdated thinking from the age of Cold War and zero-sum game,” he intoned. Xi then outlined this proposal:

China proposes that we make CICA a security dialogue and cooperation platform that covers the whole of Asia and, on that basis, explore the establishment of a regional security cooperation architecture. China believes that it is advisable to increase the frequency of CICA foreign ministers’ meetings and even possibly summits in light of changingsituation, so as to strengthen the political guidance of CICA and chart a blueprint for its development.

What are the implications of Xi’s CICA presentation for his trip to South Korea? I suggest that there are two: the importance of close inter-Asian economic relations, and, on that foundation, the desirability of creating an all-Asian security architecture. He fulfilled the first by reaching agreements with Seoul that promise strong bilateral trade and investment growth. The second item suggests a way to exclude the US from regional security issues, especially maritime territorial disputes, without demanding a rupture in the US alliance system and potentially improving prospects for resumption of the Six Party Talks. Clearly, in both instances China would strengthen its image as a leader in East Asia. But from the ROK’s perspective, joining a dialogue forum without the US is probably unaccceptable.

Mel Gurtov is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University, Editor-in-Chief of Asian Perspective, and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. His latest book is Will This Be China’s Century? A Skeptic’s View (Lynne Rienner, 2013). His foreign affairs blog, “In the Human Interest,” is here. An earlier version of this article appeared in China-US Focus.

Notes

1 For a comprehensive report on the current state of Sino-Japanese relations, see the International Crisis Group’s “Old Scores and New Grudges: Evolving Sino-Japanese Tensions,” July 24, 2014.

2 “Interview: Xi’s Visit to Strengthen Strategic Cooperative Partnership with South Korea—Ambassador,” July 3, 2014.

3 “China-ROK Pursue FTA to Conclusion,” July 5, 2014.

4 Kwanwoo Jun, “Seoul Affirms Interest in Joining TPP,” http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2014/01/13/seoul-affirms-interest-in-joining-tpp-but-says-china-deal-comes-first/

5 The Chinese text of the final statement is here.

6 See, for example, Wang Yiwei, “Strategic Significance of China-ROK Relations,” July 7, 2014. Wang Yiwei is director of the International Affairs Institute at Renmin University.

7 “‘No’ to US Missile Defense,” Korea Times, July 22, 2014.

8 Stefan Soesanto, “Missile Defense and the North Korean Nuclear Threat,” June 7, 2014.

10 Yi Whan-woo, “NK Criticizes China for Joining U.S.-led Condemnation,” Korea Times, July 24, 2014.