Children of the “Dirty War”: Argentina’s Stolen Orphans

Letter from Argentina about the children of the disappeared.

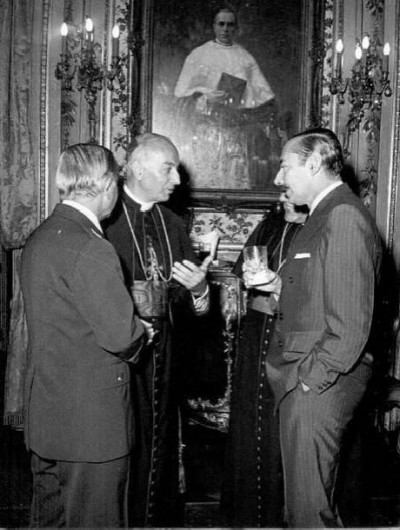

[image: Leader of the Military Junta General Jorge Videla with the Vatican’s nuncio Pio Laghi]

During the Process of National Reorganization—the military junta’s grandiose name for the period of its rule, from 1976 to 1983—as many as thirty thousand people, mostly young Argentines, were disappeared. The government justified its tactics as part of a war against a revolutionary insurrection waged by “subversive terrorists,” though the junta’s first leader, General Jorge Rafael Videla [see image], defined a “terrorist” as “not only someone who plants bombs but a person whose ideas are contrary to Western, Christian civilization.”

Pregnant prisoners were routinely kept alive until they’d given birth. Sometimes the mothers were able to nurse their newborns, at least sporadically, for a few days, or even weeks, before the babies were taken from them and the mothers were “transferred”—sent to their deaths, in the Dirty War’s notorious nomenclature.

A common method of “transfer” was to inject the women with drugs and shove them from planes into the River Plate or the Atlantic. According to human-rights groups, as many as five hundred newborns and young children were taken from disappeared parents and handed over, their identities erased, to childless military and police couples and others favored by the regime.

It has long been assumed that these baby thefts arose partly from the military’s collusion with sectors of the Catholic Church, which gave its blessing to the death flights but not to the murder of young or unborn children. The Process of National Reorganization wanted to define and create “authentic Argentines.”

The children of subversives were seen, author Marguerite Feitlowitz explained, as “seeds of the tree of evil.” Perhaps through adoption, those seeds could be replanted in healthy soil. Tells about the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, who made it their goal to find those adopted children and restore them to whatever remained of their biological families. Discusses in detail the case of Marcela and Felipe Noble Herrera, who were adopted by Ernestina Herrera de Noble, the widow of Roberto Noble, the founder of Argentina’s Clarín media empire.

Read more:

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/03/19/120319fa_fact_goldman#ixzz2OC4sEyn5

Copyright: The New Yorker, 2013