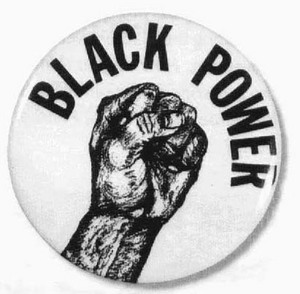

Black Power–White Backlash: 150 Years of Struggle for National Liberation and Socialism

Since the Civil War Africans have been on the frontline of the movement against oppression and economic exploitation

This year represents the 50th anniversary of the Black Power Movement emanating from the struggle for Civil Rights largely centered in the South of the United States.

1966 marked a turning point in efforts that had lasted for over a century aimed at winning full equality and self-determination for the descendants of enslaved Africans. Since the demise of chattel slavery as an economic system the capitalist ruling class has maintained its grip on the U.S. and indeed large swaths of territory throughout the world.

What role did African people play in both building the system of capitalism and challenging its hegemony? At what stage is the renewed campaign against racism and the extent to which it will hopefully take the struggle for self-determination, social justice and socialism aimed at transforming the state and society?

In this presentation we will examine some aspects of the Post-Civil War period including the issuance and passage of a series of Civil Rights measures such as: General William Sherman’s Order No. 15; the 13th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866; the 14th and 15th Amendments. These developments will be placed in their social and political context.

The African American struggle against national oppression and economic exploitation has continued through the 20th century with the anti-segregation and women’s movements of the 1950s through the 1970s up until the anti-racist struggles today against police terrorism and for self-determination in the workplace, public service, education and cultural affairs. With 2016 being an election year it is important that we review some of the important historical developments that are continuing to shape the politics of the second decade of the 21st century.

The Historical Importance of the Civil War

By 1860 there were nearly four million Africans living in slavery and another half-million designated as free human beings. Altogether 11 states seceded from the United States by early 1861.

African labor was indispensable in the growth and profitability of the European, Latin American and North American economic systems. This fact has been examined by numerous historians including Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, Dr. Eric Williams, Dr. William A. Hunton, Walter Rodney, Prof. Gerald Horne, and many others.

The desire to maintain the economic system of slavery resulted in a split within the U.S. and a horrendous Civil War that resulted in over 600,000 deaths, over a million injuries and the displacement of millions more resulting in the large-scale social destruction of the slaveholding South which lasted for well over a century. After the war industrial capitalism, whose growth was fueled by the profits from the Atlantic Slave Trade, became the dominant economic system in the U.S. and internationally.

Sentiments towards secession escalated rapidly after the election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln as president in November 1860. The Republicans were considered the party of abolition and consequently the Southern ruling class felt threatened that the economic basis of their existence was being systematically undermined.

Only two days after the national elections, the state legislature in South Carolina called for a special convention on December 20. During this gathering the representatives voted unanimously for separation from the Union. In the following six weeks other states—Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas—also voted to secede from the U.S.

Later Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee had decided to leave by June of 1861 some two months after the war had begun with the attack by Lincoln’s forces on Fort Sumter in South Carolina. The state of Tennessee was the last to withdraw from the Union when Gov. Isham D. Harris, a proponent of the Confederacy since early 1861, utilized the request for volunteers by Lincoln as a rallying cry for the white settlers to support secession. Harris said in response to Lincoln’s request for recruits, that “Tennessee will not furnish a single man for the purpose of coercion…but 50,000 if necessary for the defense of our rights and those of our Southern brothers.”

By the conclusion of the summer of 1862, the Confederate armies were on the march towards capturing Washington, D.C. Africans who had run away from the plantations and taken refuge in Union military camps began to receive training. A regiment of African troops were prepared for battle in Indiana yet Lincoln was reluctant to deploy them.

Soon enough Confederate General Robert E. Lee crossed the Potomac River at Leesburg, Virginia. This dramatic march north created panic in the capital while ships were placed on standby to transport Lincoln and his Cabinet out of Washington to an undisclosed location. General George B. McClellan was given command of the 90,000 men in the Army of the Potomac.

Facing an escalating military crisis, on September 22, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, set to go into effect on January 1, 1863, saying “And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons. And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages. And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

By the conclusion of the war some 186,000 African troops had served in the Union army and contributed to its ultimate victory. Nonetheless, the question of what was to become of the former enslaved and their free counterparts was yet to be settled.

Even with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in January 1865 and its ratification by December, it did not grant the right to vote to the African people. General William Sherman’s Field Order No. 15 aimed at the redistribution of 400,000 acres of land to freed slaves living on the coast of the southeast states of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, was designed to assist in building loyalty to the Union as well as facilitate the building of some semblance of an independent existence for those who were freed from bondage.

Nonetheless, after Lincoln’s assassination the order was rescinded by President Andrew Johnson and the seized Confederate land was returned to the Planters. Africans gained land in the South as a result of the unstable social and political conditions facing the region during and after Reconstruction.

A series of Civil Rights legislative measures were enacted from 1866-1875. These included:

The Civil Rights Act of 1866—“mandated that ‘all persons born in the United States, with the exception of American Indians, were ‘hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.’ The legislation granted all citizens the ‘full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property.’” (history.house.gov)

The Reconstruction Act of 1867—divided the South into five military districts initiating the period of greater African American participation in local, state and federal government including legislative branches.

14th Amendment—was passed in 1866 and ratified two years later in 1868. It also said that all persons born in the U.S. were citizens. Therefore, ostensibly granting citizenship rights to freed Africans.

15th Amendment—granted African American men the right to the franchise. Saying “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1875—often referred to as the Enforcement Act or Force Act, was passed in an atmosphere of rising reaction throughout the U.S. The bill was “introduced by one of Congress’s greatest advocates for black civil rights, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, in 1870. The original bill outlawed racial discrimination in juries, schools, transportation, and public accommodations. Republican leaders were forced, however, to chip away at the legislation’s protections in order to make it palatable enough to pass in the face of growing public pressure to abandon racial legislation and embrace segregation.” (history.house.gov)

During this period African Americans were elected to Southern state governmental structures, appointed as civil servants and were placed as well as voted into the Congress and the Senate. Nevertheless, the former Confederates fought these reforms with a vengeance forming the Ku Klux Klan in 1865 leading to a reign of terror that extended into the mid-1960s.

History.com website summarizes this period noting “Under the administration of President Andrew Johnson in 1865 and 1866, new southern state legislatures passed restrictive ‘black codes’ to control the labor and behavior of former slaves and other African Americans. Outrage in the North over these codes eroded support for the approach known as Presidential Reconstruction and led to the triumph of the more radical wing of the Republican Party. During Radical Reconstruction, which began in 1867, newly enfranchised Blacks gained a voice in government for the first time in American history, winning election to southern state legislatures and even to the U.S. Congress. In less than a decade, however, reactionary forces–including the Ku Klux Klan–would reverse the changes wrought by Radical Reconstruction in a violent backlash that restored white supremacy in the South.”

1966 and the Rise of Black Power

Consequently, the next century would be one of strife and struggle for the African American people. Not only did the Compromise of 1877 effectively end Federal Reconstruction, although it did continue at the local and state levels in several Southern states until the conclusion of the 1890s, it also prevented the question of the rights of women to become a focus of debate within official political channels.

African American women and men had supported women’s suffrage even during the period of slavery and its immediate aftermath. Frederick Douglass was a proponent of abolition and full voting rights for all women long before the 19th amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1920.

Organizational expression of the women’s movement took on forms through African American churches and civic groups. A women’s club movement grew exponentially during the 1890s coinciding with the anti-lynching campaign of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and others.

Women were involved in the early phase of the Pan-African Movement in Europe and the United States between 1893 and 1927. Wells-Barnett was a co-founder of the NAACP in 1909 acting in her capacity as a journalist, researcher, publisher, an advocate for women’s rights and other issues.

Two World Wars brought millions of African Americans into the military services and the industrialization process catapulted by global conflict fostering the migration of millions from the rural and urban South to the North and West. Other migration trends out of the South during the late 19th century took thousands to Kansas, Oklahoma and as far away as Liberia in West Africa.

The modern day Civil Rights Movement gained a mass character in December 1955 with the commencement of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. By 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had been formed out of the sit-ins. The 1961 Freedom Rides to break down segregation in interstate commerce emboldened the students and workers to expand mass demonstrations in Albany, Birmingham, Selma, Cambridge, Danville, and other areas.

In June 1963, Detroit mobilized hundreds of thousands in the largest Civil Rights march in U.S. history led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev. C.L. Franklin, Rev. Albert B. Cleage and other leaders. Two months later the March on Washington gained international attention for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who emerged during the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56 forming the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957.

President John F. Kennedy had announced the introduction of yet another Civil Rights Bill, the first since 1957, in June 1963. Limited progress had been made towards its passage by the time Kennedy was assassinated on November 22.

Even with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the concrete conditions of African Americans remained oppressive. Rebellions erupted in Watts in 1965 and later in Chicago, Cleveland, and other cities in 1966.

The first effort to organize an independent political party under the symbol of the Black Panther took place in Lowndes County, Alabama in 1965-66. It was out of this project that Stokely Carmichael gained even more notoriety and was elected as chairman of SNCC in May of 1966.

In 1966 the term “White Backlash” entered into the political lexicon of the U.S. An attempt to pass a Civil Rights Act of 1966 failed in Congress due in large part to the perception by many whites within the ruling class and their allied political parties that the advent of militant Civil Rights demands, the Black Power Movement, urban rebellions and growing opposition to the President Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam exemplified that year by SNCC, went beyond what was considered acceptable demands.

By March-April 1967, King would join SNCC and other progressive forces in public opposition to the war sealing his fate with the U.S. government. When he was assassinated in April 1968, rebellion erupted in 125 cities across the country. Just in the prior year of 1967, 164 rebellions were recorded as discontent with the system of national oppression, capitalism and imperialism accelerated.

These developments in the U.S. coincided with a broader worldwide revolutionary movement in various regions of Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. The advent of the socialism in the former Soviet Union, China, Democratic Korea, North Vietnam, Cuba, Yugoslavia, etc., provided a political and economic alternative to capitalism and imperialism. Many of the liberation movements in Africa moved towards Marxist ideology along with the most advanced states emerging from colonial rule.

A concerted government policy to reverse the gains of the Civil Rights, Black Power, Anti-War, Anti-Imperialist and revolutionary movements was well underway by the Johnson administration in 1967. Widespread demonstrations, civil unrest and rebellion severely damaged the image of the U.S. as a “democratic” state concerned with human rights both domestically and internationally. As the U.S. lost more battles in Vietnam, other liberation fronts throughout Southeast Asia and internationally observed that Washington and Wall Street were not invincible.

Imperialism and capitalism could be defeated and a completely different method of organizing society was proving to be not only possible, but viable. The socialist and independent states began to outstrip the West in areas of science, healthcare, the elimination of racism and gender discrimination, and by also empowering the working class, national minorities and peasants.

With specific reference to our interest is the notion of revolutionary organization to transform the racist, capitalist and imperialist system. Reforms initiated during the 1950s-1970s were reversed in a similar fashion as the events which unfolded after 1877.

After forming the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in October 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, set the stage for further armed confrontations with law-enforcement. Police brutality had been common practice in the U.S. even in the rural and urban South where agents worked in close cooperation with the agricultural and industrial bosses along with the bankers.

Another major theoretical contribution of the BPP was its position on the women’s question. The Party encouraged women to take leadership positions in the areas of political education, mass organizing and military defense. There were at least two women that served on the Central Committee of the Party while others ran offices, the free breakfast programs and conducted political education classes.

The U.S. government under both Johnson and President Richard M. Nixon, who took office in January 1969, had as one of its primary objectives the defeat of the armed resistance to occupation by the Vietnamese and the eradication of the revolutionary movement in the U.S. From its earliest period the Party sought to form alliances on an international level with the socialist countries and national liberation movements.

By August 1969, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver of the BPP among others had established an International Section in the North African state of Algeria while attending the Pan-African Cultural Festival. Cleaver had attended an international journalist conference in the DPRK where relations were established. Meetings were held earlier with the Vietnamese in 1967 when Carmichael consulted Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi and later after the International Section was established.

There were other revolutionary organizations founded during this period, including the two most significant being formed right here in Detroit. These organizations are the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW), established in 1968-69 as well as the Republic of New Africa formed in March 1968. The LRBW and its affiliates operated in the plants and other workplaces in addition to the schools, universities and neighborhoods.

In Detroit ideas related to the building of alternative centers of power whether they were in the plants, on the campuses and in the communities, took on broader dimensions than in other cities. The efforts of the revolutionary movement led directly to the creation of viable reforms including affirmative action programs, the election of African Americans to public office including the state legislature, city council and the mayor’s office in 1973 with the ascendancy of Coleman A. Young.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) along with other tactics utilized by the Central Intelligence Agency, the U.S. military and the corporate community, attacked the Black Liberation Movement with a ferocity that was unparalleled in the history of the country. Hundreds of the principal organizers of the movement were arrested on trumped-up and politically motivated charges. Many would spend years in prison or in forced exile as is the case with Albert Woodfox, Assata Shakur, Mutulu Shakur, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Nehanda Abiodoun, Sundiata Acoli, Leonard Peltier, Oscar Lopez Rivera, to name only a few.

Dozens of others were assassinated such as Bobby Hutton, Fred Hampton, Mark Clark, Ralph Featherstone, Che Payne Robinson, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., George Jackson, 11 MOVE members, Hugo Pinnell, etc. Moreover, the COINTELPRO project was designed to discredit the revolutionary movement and prevent it from gaining respectability among youth and the broader working class. A revolutionary culture was counter-posed with materialism and individualism. The liberation of women, gender equality, LGBTQ emancipation were projected as “wedge issues” contrasted with purportedly other more important questions such as corporate profitability, national security for the capitalist system, military hegemony for the imperialist military structures and unbridled control of the media where ruling class propaganda is disseminated around the clock in an attempt to both confuse and demoralize the masses.

Within the area of jurisprudence, legal decisions have been rendered since the late 1970s which have in essence reversed the trajectory of Civil Rights law that emerged from the 1940s through the 1960s. Affirmative Action has been virtually outlawed in numerous states including Michigan and California. Right-to-work legislation has been passed in Michigan, the birthplace of automotive unionism, along with Wisconsin where labor rights and social democracy found a base for over a century.

State governments and local entities at the will of the corporate and banking elites abrogate fundamental laws of self-rule, due process and the right to vote. The imposition of emergency management in its most brutal form was carried out in contravention of the electorate. The forced bankruptcy of Detroit, the largest in municipal U.S. history, was conducted without a vote of the people or their representatives. The transfer of administration, ownership and control of public assets such as the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department, the Detroit Public Schools, Belle Isle, the Detroit Institute of Arts, etc. never faced public scrutiny on an official level or were done without the approval of voters.

As we have stated before, the contradictions within the current capitalist crisis does not permit even the purported “sanctity” of bourgeois democratic practice. The U.S. political system routinely violates its own laws and regulations since the capacity for the changing of legal codes often lags behind the imperatives of the exploitative system.

Objectively the conditions of African Americans, Latinos, working class women, and the proletariat as a whole have worsened over the last four decades. Despite the official jobless rate being calculated at less than five percent, the labor participation rate is the lowest since the mid-1970s. Half of the people in the U.S. are either living in poverty or near this level. Discontent runs deep with the system as is exemplified in the current phase of the struggle.

Black Power and the White Backlash in 2016

Since this is an election year the question of race and economics are coming to the fore once again. The situation in Flint is indicative of what the future of the U.S. may look like. In actuality, Flint is by no means the only city in the country where tap water is undrinkable. What has distinguished the crisis in Flint is that the people have spoken out against these crimes and are demanding that the state and federal governments do something to correct it immediately.

Despite months of press coverage and visits by a host of activists, politicians and celebrities, the holding of a hearing in Congress and the donations of millions of bottles of water, not one pipe has been dug up and replaced in the city. The “assistance” provided by the state and federal government has more to do with covering up the crimes of those responsible than holding them accountable in the overall process of rebuilding and seriously addressing the burgeoning healthcare and human services crises.

Then of course we have the intervention of Hillary Clinton who speaks to African Americans in a church and places this as the main focus of campaign ads. The mayor of Flint is seen in a commercial telling people they should vote for Clinton.

Now the African American people are called upon to rally behind the Democratic Party ostensibly to stave off the potential horrors of a Donald Trump presidency. Nonetheless, how did African Americans really fair under the Clinton administration of the 1990s?

For those with historical amnesia we wish to remind you to take a cursory view of such measures as the “elimination of welfare as we now it”; the ominous crime bill; the effective death penalty act; the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); placing a hundred thousand of new cops on the streets; the further deregulation of the financial industry leading to predatory lending as official policy resulting in the loss to millions of their homes to the banks; the building of prisons and increasing mass incarceration to lock up the so-called “super-predators.”

On a foreign policy level we must recount the continuation of the war and sanctions program against Iraq resulting in the deaths of a million people, many of whom were children; the bombing of Sudan destroying a pharmaceutical plant under the false allegation that it was a chemical weapons factory; the institution of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) which may sound good but in practice perpetuates imperialist interference and control of the economic affairs of the continent; fostering globalization, which is just a modern term for imperialism through the World Trade Organization and the Free Trade Area of the Americas; just to name some of the most well-known policies of the Clinton era.

After eight years of the Bush administration and the expansion of the “war on terrorism” along with the maintenance of the prison-industrial and military-industrial complexes, the current administration of President Barack Obama must be analyzed objectively as well. The failure of the administration to address the special oppression of African Americans has been exposed through the outrage prompted by blatant police and vigilante killings of youth across the country.

African Americans remain disproportionately impoverished, imprisoned, socially marginalized and susceptible to political manipulation. Clinton stands in the pulpit of a Flint church as if to say “these are my people”; yet when she served as the Secretary of State in the first Obama administration the North African state of Libya, the most prosperous and stable on the continent, was destroyed by Pentagon bombs, naval blockades, the expropriation of national wealth and the funding of counter-revolutionary militias acting as ground troops of the imperialist system.

Today Libya not only lies in ruin but has become a haven for the Islamic State, the dreaded “terrorist organization” which Clinton and Trump are saying they will destroy. How can they destroy IS when U.S. imperialism created it as a bulwark against Iranian influence in Iraq and Syria?

The regime-change policy towards Libya and Syria has contributed immensely to the worse humanitarian and displacement crisis since the conclusion of World War II. Some 60 million people have been displaced both within and outside their borders. Millions are trafficked through Libya to other states and regions including across the Mediterranean into Southern, Central and Eastern Europe. Racism and xenophobia are escalating inside Europe dividing the EU and fueling ultra-right wing fascist organizations and parties.

Inside the U.S. mass demonstrations and urban rebellions against racist violence have occurred over the last three years in response to the brutal unpunished vigilante murder of Trayvon Martin as well as the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in New York and Freddie Grey in Baltimore . The Black Lives Matter Movement, by no means a uniform organization, which has its own contradictions stemming from this reality, is still subjected to a renewed form of COINTELPRO.

Spontaneity and the Mass Struggle: The Need for a Revolutionary Party

There is no doubt that anger is mounting in the city of Detroit and throughout the U.S. This unease exists outside the fact that organizations similar to the Black Panther Party and other revolutionary groups are not in evidence nationally in the current period.

Consequently there is an important role to play for a Marxist-Leninist Party committed to organizing the working class and the nationally oppressed. The character of the oppressive state must be laid bare before the masses. The systematic oppression of the African American people and the working class in general lies at the heart of the crisis, which derives from the contradictions between the ownership of capital and the means of productions with the actual relations of production.

We have worked for substantial reforms not as end unto themselves but as a method of exposing the need for revolution by illustrating the character of the state as a reflection of the inherently exploitative system of capitalism. African Americans and other oppressed nations can only win genuine liberation through socialist revolution. The state must be transformed as a mechanism to ensure the right to self-determination, independence, social justice and full equality. Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans can bring total freedom since they are controlled by the same class forces representing the owners of capital.

This is why we need a revolutionary party independent of the bourgeoisie which is willing to organize the people based on their national and class interests. We are not opportunists who go before the masses and tell them if they vote for ruling class allied politicians that conditions will improve for their communities.

We must fight for the fundamental political and economic rights of the people while at the same time emphasizing consistently that the system is rotten to the core. As V.I. Lenin stressed in 1903 in “What Is to Be Done?– The Burning Issues of Our Movement”, “we have become convinced that the fundamental error committed by the ‘new trend’ in Russian Social-Democracy is its bowing to spontaneity and its failure to understand that the spontaneity of the masses demands a high degree of consciousness from us Social-Democrats. The greater the spontaneous upsurge of the masses and the more widespread the movement, the more rapid, incomparably so, the demand for greater consciousness in the theoretical, political and organizational work of Social-Democracy.”

Lenin goes on to say that “The spontaneous upsurge of the masses in Russia proceeded (and continues) with such rapidity that the young Social Democrats proved unprepared to meet these gigantic tasks. This unpreparedness is our common misfortune, the misfortune of all Russian Social-Democrats. The upsurge of the masses proceeded and spread with uninterrupted continuity; it not only continued in the places where it began, but spread to new localities and to new strata of the population (under the influence of the working class movement, there was a renewed ferment among the student youth, among the intellectuals generally, and even among the peasantry). Revolutionaries, however, lagged behind this upsurge, both in their ‘theories’ and in their activity; they failed to establish a constant and continuous organization capable of leading the whole movement.”

These words ring true today. Our task before us today is to build a revolutionary party with the capacity to continue the struggle against all odds. Please join us in this challenge.

Note: This keynote address by Abayomi Azikiwe was delivered at the Annual African American History Month public meeting held on Saturday February 27, 2016 and sponsored by Workers World Party Detroit branch.

The program was chaired by Debbie Johnson of Workers World while greetings were delivered by Stacey Rogers of the International Longshoreman and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 10, who discussed a resolution passed recently by her local in the Bay Area of California in solidarity with the people of Flint poisoned through their water services by the state of Michigan; Clarence Thomas, the former Secretary-Treasurer of the ILWU Local10, who is in the area for a solidarity mission with the city of Flint.