Bernie Sanders: “I Think I’d Make a Good Candidate”

This is the eleventh chapter from “Maverick Chronicles,” a memoir. Other stories can be found at VTDigger and Global Research.

“I think I’d make a good candidate,” said Bernie Sanders. We were sitting across a small table in the Fresh Ground Coffee House, the same place the FBI had labeled a “known contact point” for extremists a few years earlier. As far as I knew no spooks were listening.

In October 1980, most people were focused on the presidential race between Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. But a few of us were looking beyond the two-party system. Sanders supported Socialist Workers Party candidate Andrew Pulley, on the Vermont ballot that year along with four other “minor” party hopefuls. I backed Barry Commoner, who had formed the Citizens Party a year earlier. The reason for the meeting wasn’t national politics, however. Both of us were thinking about the race for mayor the following March.

As editor of The Vermont Vanguard Press I had crossed the line from observer to participant. Earlier in the year I’d attended the founding of the new party’s Vermont chapter and pushed for a race against incumbent congressman James Jeffords (who left the Republican Party two decades later). The Democrats had opted not to put up a candidate. The Citizens Party’s choice was Robin Lloyd, a peace activist and advocate for a nuclear weapons freeze since the birth of our son Jesse in 1978. Further complicating the picture, I was chairing the Burlington City Committee of the party, and let it be known that if Robin did well locally, I might build on the momentum by running for mayor.

As it turned out, Robin won about 13 percent of the statewide vote, an impressive number for a first-time candidate in the race only six weeks against a popular incumbent. But another important number was 25, the percentage of the vote she won in Burlington. To those paying close attention, this suggested that a candidate not in one of the major parties could potentially mount a local challenge. When we met neither Bernie Sanders nor I knew how well Robin would do. But we both sensed the potential.

The truth is that it was not a negotiation. As Bernie made plain, he planned to run no matter what anyone else did. Since leaving the Liberty Union Party in 1977 and declaring it a failure he had been working as a filmstrip producer and building a political base in the city’s New North End. Joining forces with tenants at a public housing project, he formed an advocacy group, then a campaign exploratory committee that included local activists and UVM faculty. He planned to run as an independent, he said, and create a loose coalition.

Some people had doubts about his move. Even Bernie wondered whether he could focus on local issues instead of blasting millionaires. “National and state issues are more my thing,” he acknowledged But the word was out. According to the Burlington Free Press, two “left-leaning activists” were “jockeying over who will carry the progressive banner next year.”

Sanders said he wanted to lead a coalition of poor people, blue-collar workers and university students. “The goal must be to take political power away from the handful of millionaires (he’d managed to get them in the mix) who currently control it through Mayor Paquette, and place that power in the hands of the working people of the city,” he announced.

My approach was more local and granular. Building on the issues I’d been pursuing as Vanguard Press editor for several years, I talked about building low and moderate income housing, establishing neighborhood councils, diversifying the economy, stopping the Southern Connector highway, and “linking development to human needs.” Allies urged me to run despite Bernie’s announcement, and suggested forthcoming support from some Democrats since I “sounded more moderate.”

Although Sanders’ rhetoric did make it appear that he was “further to the left,” when push came to shove he turned out to be pragmatic about policy choices, and quite comfortable with the exercise of power. His approach was appealing to broad constituencies, even some conservatives; local issues were less important to him, and in truth he knew little about them. On the other hand, he was a natural campaigner who could connect with the public.

If both of us ran, neither was likely to win. If one stepped aside, however, my prediction years earlier about overturning the local political establishment might come true.

A few days after the November elections, I phoned in my decision to the Free Press. “I don’t really want to be in the position of dividing progressives looking for an alternative to Paquette,” I explained.

Dropping out of the race was a tough choice, and I wasn’t completely comfortable with Sanders heading the ticket of a movement I had spent much effort and many years helping to build. But faced with the opportunity to plunge seriously into electoral politics, I decided to pass. Two years later I rejected the Citizens Party nomination to run for Vermont governor, along with backing from a faction in the national Party who wanted to replace Barry Commoner as chair.

The way I saw it at the time, Bernie was an instinctive politician and I was not. He enjoyed campaigning and knew how to give the same speech, over and over, while connecting viscerally with his audience. He also knew how to wage ideological war and manipulate the media, without scruples or over-dependence on facts to make his case. On the other hand, he wanted to lead this emerging movement without submitting to the dictates of any leadership. And he conveniently separated a professed dedication to democracy from his personal practice, which soon led to autocratic actions and shutting down the opinions of allies with the temerity to disagree.

The way I saw it at the time, Bernie was an instinctive politician and I was not. He enjoyed campaigning and knew how to give the same speech, over and over, while connecting viscerally with his audience. He also knew how to wage ideological war and manipulate the media, without scruples or over-dependence on facts to make his case. On the other hand, he wanted to lead this emerging movement without submitting to the dictates of any leadership. And he conveniently separated a professed dedication to democracy from his personal practice, which soon led to autocratic actions and shutting down the opinions of allies with the temerity to disagree.

As one supporter confided, “He’s a jerk. But he’s our jerk.”

In January 1981, Gordon Paquette was nominated for a fifth term as Burlington Mayor. After the Democratic caucus Richard Bove, owner of a popular local Italian restaurant who was defeated in the caucus, bolted the party to run as an independent. Republican leaders decided not to oppose Paquette and instead banked on his re-election.

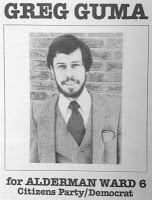

Rather than sit out the campaign I ran as a Citizens Party candidate for the City Council against Richard Wadham Jr., preppy chair of the Republican City Committee. The Citizens Party fielded candidates in two other wards. Our opponents tried to ignore us, assuming that a small group of activists had no chance of upsetting the status quo. They seriously underestimated the growing influence of neighborhood groups, housing reformers and redevelopment opponents, young people and the disgruntled elderly. They also ignored the possibility that some of Paquette’s past supporters might choose to send him a message.

On March 3, 1981, with a few thousand dollars, a handful of volunteers and a vague reform agenda, Bernie Sanders won the race by ten votes. Burlington had a radical mayor, a self-described democratic socialist who was determined to change the course of Vermont history.

I lost my council race with 42 percent of the vote, but another Citizens Party candidate, Terry Bouricius, became the first member of the party elected anywhere in the country. In an odd twist of fate, he won in Ward Two, the same neighborhood that had given Mayor Paquette his first term on the City Council 23 years before.

Over the next decade there were remarkable advances in the Queen City, as well as several missteps. Some early progressive initiatives actually challenged the basic logic of capitalism, but others simply provided benefits while leaving the system unchanged. A few contradicted the public rhetoric, however, raising doubts about the priorities of the new movement and creating divisions that endured.

Beginning in 1983, for example, protests at the local General Electric armaments plant led to painful arguments: activists wanted a city commitment to peace conversion, Sanders and other progressives preferred to turn the heat on Congress. It was basically a dispute over tactics, but the implications went deeper. By opposing the GE protests and having the protesters arrested, Bernie appeared to protect the corporation and the military-industrial complex behind it. His position also contradicted strong local pronouncements on intervention in Central America. At the very least, Sanders’ commitment to an industrially-based socialism was colliding with the community-based peace movement’s commitment to ending foreign intervention and violence. The casualties were some mutual trust – and the workers who later lost their jobs as demand for GE’s Gatling guns waned.

The working relationship between Sanders’ City Hall and the peace movement usually went more smoothly. And the results were indisputably significant. Burlington developed, and, to a limited extent, implemented aspects of a foreign policy. A series of citywide votes established the framework – cooperation and exchanges with the Soviet Union, opposition to intervention, people-to-people programs and exchanges. Designed to change consciousness and challenge knee-jerk anti-Communism, they did exactly that.

Between 1981 and 1987, Burlington voted to cut aid to El Salvador, oppose crisis relocation planning for nuclear war, freeze nuclear weapons production, transfer military funds to civilian programs, condemn Nicaraguan Contra aid, and divest from companies doing business with apartheid South Africa. Supporting the efforts of the independent peace movement, Sanders was a consistent voice for a new foreign policy.

Did all the resolutions, statements, and even diplomatic links with Nicaragua pose a threat to capitalist interests? Hardly. But they contributed to a change in basic attitudes, and meshed well with the efforts of others activists around the state. By the end of the 1980s, most Vermont politicians supported disarmament and a non-interventionist foreign policy. Peace and, to a limited extent, social justice became mainstream positions.

The thrust of reform during the early years of Burlington’s progressive realignment was primarily economic, driven by the mayor’s reform-oriented, “sewer socialist” approach. It wasn’t that other issues were ignored; the administration’s record on youth programs, tenants’ right, and women’s issues was impressive. Rather it was a matter of priorities and focus. Issues affecting women and gays did take a back seat sometimes, or were handled indirectly as matters of economic justice.

After 1981 Burlington became a more dynamic, open community. During this same time, the unemployment rate was virtually the lowest in the nation. The cultural forces set loose, and nourished by local government, made the urban core more magnetic than ever. But there were clouds on the horizon, some new, others gathering force after years of neglect. The side effects of success included things like traffic jams and high rents, toxic dumps and a landfill crunch, gentrification, the feminization of poverty and a rush to redevelopment.