“Anti-Americanism” in the Philippines. President Duterte’s Subaltern Counter-Hegemony

Guerilla Incursions from the Boondocks

“A howling wilderness” was what General Jacob Smith ordered his troops to make of Samar, Philippines. He was taking revenge for the ambush of fifty-four soldiers by Filipino revolutionaries in September 1901.

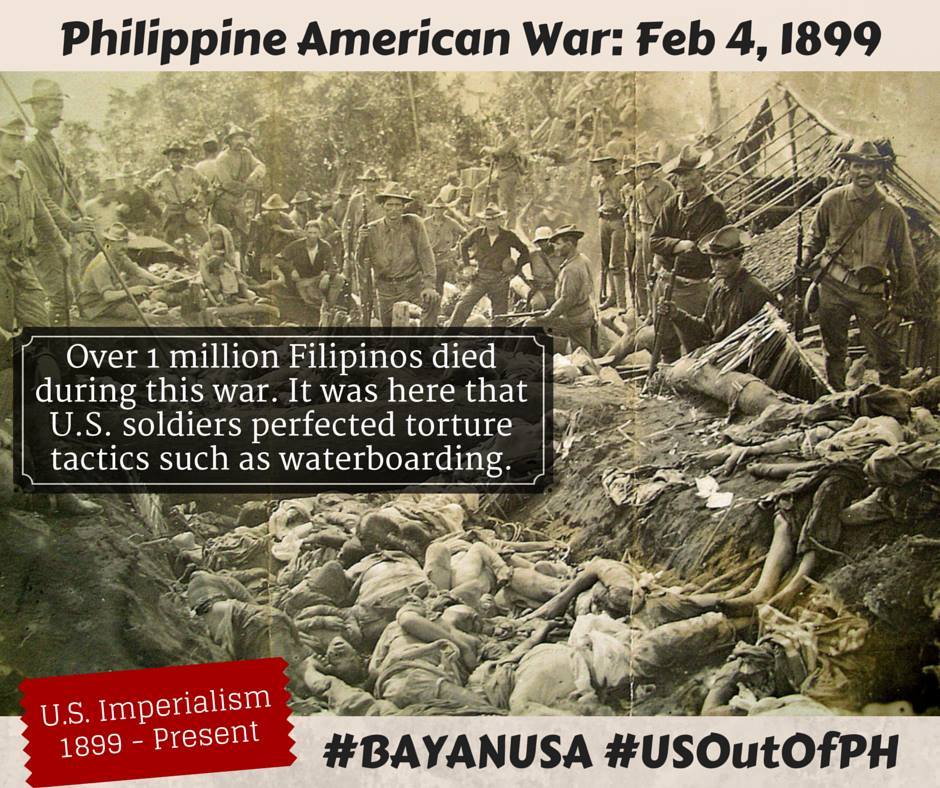

After the invaders killed most of the island’s inhabitants, three bells from the Balangiga Church were looted as war trophies; two are still displayed at Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne, Wyoming. Very few Americans know this. Nor would they have any clue about the 1913 massacre of thousands of Muslim women, men and children resisting General Pershing’s (image right) systematic destruction of their homes in Mindanao where President Rodrigo Duterte today resides.

Addressing this dire amnesia afflicting the public, both in the Philippines and abroad, newly-elected president Duterte began the task of evoking/invoking the accursed past. He assumed the role of oral tribune, with prophetic expletives. Like the Filipino guerillas of Generals Lukban and Malvar who retreated to the mountains (called “boondocks” by American pursuers from the Tagalog word “bundok,” mountain), Duterte seems to be coming down with the task of reclaiming the collective dignity of the heathens— eulogized by Rudyard Kipling, at the start of the war in February 1899, as “the white men’s burden.” The first U.S. civil governor William Howard Taft patronizingly adopted this burden of saving the Filipino “little brown brother” as a benighted colonial ward, not a citizen.

Addressing this dire amnesia afflicting the public, both in the Philippines and abroad, newly-elected president Duterte began the task of evoking/invoking the accursed past. He assumed the role of oral tribune, with prophetic expletives. Like the Filipino guerillas of Generals Lukban and Malvar who retreated to the mountains (called “boondocks” by American pursuers from the Tagalog word “bundok,” mountain), Duterte seems to be coming down with the task of reclaiming the collective dignity of the heathens— eulogized by Rudyard Kipling, at the start of the war in February 1899, as “the white men’s burden.” The first U.S. civil governor William Howard Taft patronizingly adopted this burden of saving the Filipino “little brown brother” as a benighted colonial ward, not a citizen.

White Men’s Burden

The Filipino-American War of 1899-1913 occupies only a paragraph, at most, in most US texbooks, a blip in the rise of the United States as an Asian Pacific Leviathan. Hobbes’ figure is more applicable to international rivalries than to predatory neoliberal capitalism today, or to the urban jungle of MetroManila. At least 1.4 million Filipinos (verified by historian Luzviminda Francisco) died as a result of the scorched-earth policy of President McKinley. His armed missionaries were notorious for Vietnam-style “hamletting.” They also practised the “water-cure,” also known as “water-boarding,” a form of torture now legitimized in a genocidal war of terror (Iraq, Afghanistan) that recalls the ruthless suppression of Native American tribes and dehumanization of African slaves in the westward march of the “civilizing Krag” to the Pacific, to the Chinese market. Today the struggle at Standing Rock and Black-Lives-Matter are timely reminders. Stuart Creighton Miller’s 1982 book, “Benevolent Assimilation,” together with asides by Gabriel Kolko and Howard Zinn, recounted the vicissitudes of that bloody passage through Philippine boondocks and countryside.

Not everyone acquiesced to Washington’s brutal annexation of the island-colony. Mark Twain exposed the hypocrisy of Washington’s “Benevolent Assimilation” with searing diatribes, as though inventing the “conscience” of his generation. William James, William Dean Howells, W.E.B. DuBois and other public intellectuals denounced what turned out to be the “first Vietnam” (Bernard Fall’s rubric).

It was a learning experience for the conquerors. In Policing America’s Empire, Alfred McCoy discovered that America’s “tutelage” of the Filipino elite (involving oligarchic politicians of the Commonwealth period up to Marcos and Aquino) functioned as a laboratory for crafting methods of surveillance, ideological manipulation, propaganda, and other modes of covert and overt pacification. Censorship, mass arrests of suspected dissidents, torture and assassination of “bandits” protesting landlord abuses and bureaucratic corruption in the first three decades of colonial rule led to large-scale killing of peasants and workers in numerous Colorum and Sakdalista uprisings.

Re-Visiting the Cold War of Terror

This pattern of racialized class oppression via electoral politics and discipiinary pedagogy culminated in the Cold War apparatus devised by CIA agent Edward Lansdale and the technocrats of Magsasay to suppress the Huk rebellion in the two decades after formal granting of independence in 1946.

The Cold War Leviathan continued to operate in the savage extrajudicial killings during the Marcos dictatorship. The Marcos family were rescued by President Reagan from the wrath of millions in the February 1982 “People Power” revolt. After Marcos’ death, the Marcos family and the despot’s cadaver were allowed by then President Ramos to return.

Given the re-installment of the feudal-comprador ellite due partly to the failure of the national-democratic forces to educate, organize and mobilize the masses, the Marcos family recovered institutional power. The current reactionary Supreme Court Justices and Duterte’s link to the Marcoses are a symptom of fierce internecine conflict within the oligarchic bloc. It fosters sectarian partisanship and opportunist fantasies. The controversy over Marcos’ burial today cannot be fully assayed without factoring in, in this conjunctural crisis, the role of patronage-clientelism syndrome in the body politic and the U.S.-oriented State ideological-military apparatus of a decadent oligarchic elite.

Mournless Melancholia

U.S. Cold War Realpolitik defined Corazon Aquino’s “total war” against nationalists, progressive peasants, professionals, Igorots, Lumads—all touted by Washington/Pentagon as the price for enjoying individualist prerogatives, esp. the right to gamble in the capitalist casino. This constitutes the rationale for U.S.-subsidized counterinsurgency schemes to shore up the decadent, if not moribund, status quo—a society plagued by profound and seemingly durable disparity of wealth and power—now impolitely challenged by Duterte.

Not a single mass-media article on Duterte’s intent to forge an independent foreign policy and solve corruption linked to narcopolitics, provides even an iota of historical background on the US record of colonial subjugation of Filipino bodies and souls. This is not strange, given the long history of Filipino “miseducation” documented by Renato Constantino. Perhaps the neglect if not dismissal of the Filipino collective experience is due to the indiscriminate celebration of America’s success in making the natives speak English, imitate the American Way of Life shown in Hollywood movies, and indulge in mimicked consumerism.

What is scandalous is the complicity of the U.S. intelligentsia (with few exceptions) in regurgitating the “civilizing effect” of colonial exploitation. Every time the Filipino essence is described as violent, foolish, shrewd or cunning, the evidence displays the actions of a landlord-politician, bureaucrat, savvy merchant, U.S.-educated professional, or rich entrepreneur. Unequal groups dissolve into these representative types: Quezon, Roxas, Magsaysay, Fidel Ramos, etc. What seems ironic if not parodic is that after a century of massive research and formulaic analysis of the colony’s underdevelopment, we arrive at Stanley Karnow’s verdict (amplified in In Our Image) that, really, the Filipinos and their character-syndromes are to blame for their poverty and backwardness, for not being smart beneficiaries of American “good works.” “F—ck you,” Duterte might uncouthly respond.

Hobbes or Machiavelli?

An avalanche of media commentaries, disingenously purporting to be objective news reports, followed Duterte’s campaign to eradicate the endemic drug addiction rampant in the country. No need to cite statistics about the criminality of narcopolitics infecting the whole country, from poor slum-dweller to Senators and moguls; let’s get down to the basics. But the media, without any judicious assaying of hearsay, concluded that Duterte’s policy—his public pronouncement that bodies will float in Manila Bay, etc.—caused the killing of innocent civilians. His method of attack impressed the academics as Hobbesian, not Machiavellian. The journalistic imperative to sensationalize and distort by selective framing (following, of course, corporate norms and biases) governs the style and content of quotidian media operations.

Is Duterte guilty of the alleged EJK (extrajudicial killings)? No doubt, druglords and their police accomplices took advantage of the policy to silence their minions. This is the fabled “collateral damage” bewailed by the bishops and moralists. But Obama, UN and local pundits associated with the defeated parties seized on the cases of innocent victims (two or three are more than enough, demonstrated by the photo of a woman allegedly cradling the body of her husband, blown up in Time (October 10) and in The Atlantic, September issue, and social media) to teach Duterte a lesson on human rights, due process, and genteel diplomatic protocols. This irked the thin-skinned town mayor whose lack of etiquette, civility, and petty-bourgeois decorum became the target of unctuous sermons.

Stigma for All Seasons: “Anti-Americanism”

What finally gave the casuistic game away, in my view, is the piece in the November issue of The Atlantic by Jon Emont entitled “Duterte’s Anti-Americanism.” What does “anti-Americanism” mean—to be against McDonald burgers, Beyonce, I-phones, Saturday Night Live, Lady Gaga, Bloomingdale fashions, Wall Street, or Washington-Pentagon imperial browbeating of inferior nations/peoples-of-color? The article points to tell-tale symptoms: Duterte is suspending joint military exercises, separating from U.S. government foreign policy by renewing friendly cooperation with China in the smoldering South China Sea, and”veering” toward Russia for economic ties—in short, promoting what will counter the debilitating, predatory U.S. legacy.

What finally gave the casuistic game away, in my view, is the piece in the November issue of The Atlantic by Jon Emont entitled “Duterte’s Anti-Americanism.” What does “anti-Americanism” mean—to be against McDonald burgers, Beyonce, I-phones, Saturday Night Live, Lady Gaga, Bloomingdale fashions, Wall Street, or Washington-Pentagon imperial browbeating of inferior nations/peoples-of-color? The article points to tell-tale symptoms: Duterte is suspending joint military exercises, separating from U.S. government foreign policy by renewing friendly cooperation with China in the smoldering South China Sea, and”veering” toward Russia for economic ties—in short, promoting what will counter the debilitating, predatory U.S. legacy.

Above all, Duterte (image right) is guilty of diverging from public opinion, meaning the Filipino love for Americans. He rejects US “security guarantees,” ignores the $3 billion remittances of Filipinos (presumably, relatives of middle and upper classes), the $13 million given by the U.S. for relief of Yolanda typhoon victims in 2013. Three negative testimonies against Duterte’s “anti-American bluster” are used: 1) Asia Foundation official Steven Rood’s comment that since most Filipinos don’t care about foreign policy, “elites have considerable latitude,” that is, they can do whatever pleases them. 2) Richard Javad Heydarian, affiliated with De La Salle University, is quoted—this professor is now a celebrity of the anti-Duterte cult—that Duterte “can get away with it”; and, finally, Gen Fidel Ramos who contends that the military top brass “like US troops”—West-Point-trained Ramos has expanded on his tirade against Duterte with the usual cliches of unruly client-state leaders who turn against their masters, and seems ready to lead a farcical version of the 1968 People Power revolt, one of the symptoms of fierce internecine strife within the corrupt oligarchic bloc.

Like other anti-Duterte squibs, the article finally comes up with the psychological diagnosis of Duterte’s fixation on the case of the Davao 2002 bombing when a “supposed involvement of US officials” who spirited a CIA-affiliated American bomber confirmed the Davao mayor’s fondness for “stereotypes of superior meddling America.” The judgment seems anticllimatic. What calls attention will not be strange anymore: there is not a whisper of the tortuous history of US imperial exercise of power on the subalterns.

This polemic-cum-factoids culminates in a faux-folksy, rebarbative quip: “Washington can tolerate a thin-skinned ally who bites the hand that feeds him through crass invective.” The Washington Post (Nov 2) quickly intoned its approval by harping on Ramos’ defection as a sign of the local elite’s displeasure. With Washington halting the sale of rifles to the Philippine police because of Duterte’s human-rights abuses, the Post warns that $ 9 million military aid and $32 million funds for law-enforcement will be dropped by Congress if Duterte doesn’t stop his “anti-US rhetoric.” Trick or treat? Duterte should learn that actions have consequences, pontificated this sacred office of journalistic rectitude after the Halloween mayhem.

On this recycled issue of “anti-Americanism,” the best riposte is by Michael Parenti, from his incisive book Inventing Reality: “The media dismiss conflicts that arise between the United States and popular forces in other countries as manifestations of the latter’s “anti-Americanism”….When thousands marched in the Philippines against the abominated US-supported Marcos regime, the New York Times reported, “Anti-Marcos and anti-American slogans and banners were in abundance, with the most common being “Down with the US-Marcos Dictatorship!” A week later, the Times again described Filipino protests against US support of the Marcos dictatorship as “anti-Americanism.” The Atlantic, the New York Times,and the Washington Post share an ideological-political genealogy with the Cold War paranoia currentlygripping the U.S. ruling-class Establishment.

Predictably, the New York Times (Nov. 3 issue) confirmed the consensus that the US is not worried so much about the “authoritarian” or “murderous ways of imposing law and order” (Walden Bello’s labels; InterAksyon, Oct 29) as they are discombobulated by Duterte’s rapproachment with China. The calculus of U.S. regional hegemony was changed when Filipino fishermen returned to fish around the Scarborough Shoal. Duterte’s “bombastic one-man” show, his foul mouth, his “authoritarian” pragmatism, did not lead to total dependency on China nor diplomatic isolation. This pivot to China panicked Washington, belying the Time expert Carl Thayer who pontificated that Duterte “can’t really stand up to China unless the US is backing him” (Sept 15, 2016). A blowback occurred in the boondocks; the thin-skinned “Punisher” and scourge of druglords triggered a “howling wilderness” that exploded the century-long stranglehold of global finance capitalism on the islands. No need to waste time on more psychoanalysis of Duterte’s motivation.

What the next US president would surely do to restore its ascendancy in that region is undermine Duterte’s popular base, fund a strategy of destabilization via divide-and-rule (as in Chile, Yugoslavia, Ukraine), and incite its volatile pro-American constituency to beat pots and kettles in the streets of MetroManila.

This complex geopolitical situation entangling the United States and its former colony/neocolony, cries for deeper historical contextualization and empathy for the victims lacking in the Western media demonization of Duterte and his supporters, over 70% of a hundred million Filipinos in the Philippines and in the diaspora. For further elaboration, see my recent books US Imperialism and Revolution in the Philippines (Palgrave) and Between Empire and Insurgency (University of the Philippines Press).

E. San Juan, Jr, an emeritus professor of Ethnic Studies and Comparative Literature, was a fellow of W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University, Fulbright lecturer of American Studies at Leuven University, Belgium, is currently professorial lecturer, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, Manila