American Military Bases on Guam: The US Global Military Basing System

The island of Guam is a most remarkable place of cultural distinctiveness and resourcefulness and of great physical beauty. The Chamorro people who have lived here for 4000 years also have an historical experience with colonialism and military occupation more long-lived and geographically intensive, acre for acre, than anywhere else in the Pacific and perhaps even in global comparative scale (Aguon 2006). It is today embroiled in a debate over when, how, or if the United States military will acquire more land for its purposes and make more intensive use of the island as a whole.

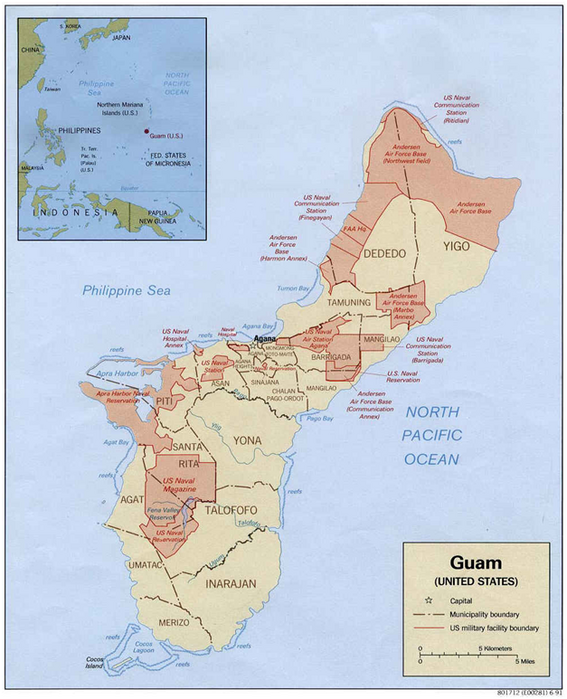

This military expansion has been planned in Washington, with acquiescence and funding from Tokyo, in order to relocate some 8,000 Marines and 9,000 dependents from Okinawa, as well as US Navy, Army, and Air Force assets and operations to Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas (CNMI) (Erickson and Mikolay 2006). The plans are breathtaking in scope, including removal of 71 acres of coral reef from Apra Harbor to allow the entry and berthing of nuclear aircraft carriers, the acquisition of land including the oldest and revered Chamorro village on the island at Pagat for a live-fire training range, and an estimated 47 percent increase in the island’s population, already past its water-supply carrying capacity. The military expansion is being planned with one-third of the island already in military hands and a substantial historical legacy of environmental contamination and depletion, external political control, and other problems brought by the existing military presence.

Pushback has been substantial, something that is particularly remarkable in a context in which many islanders consider themselves very loyal and patriotic Americans and many have military paychecks or pensions as soldiers, veterans, or contract workers (Diaz 2001). Dissent among a variety of Guam’s social sectors rose dramatically with the appearance of a draft Environmental Impact Statement in November 2009 which first made clear how extensive Washington’s plans for the island were (Natividad and Kirk 2010). It rose, as well, when it became clear that Guam’s political leaders and citizens were to be simply informed of those plans, rather than consulted or asked permission for the various uses. That dissent received support from movements against simultaneous US base expansion plans in Okinawa and South Korea, as well as from the US EPA response to the draft EIS, which found it deeply inadequate as a fair and clear assessment of the environmental costs of the military’s desires. The Final EIS, just released at the end of July, puts the aircraft carrier berthing plan on hold and draws out the buildup timeline to lower the population growth rate, but otherwise retains its scale and scope. A demonstration at a sacred site at Pagat on July 23, 2010 provided the most potent symbolic expression of resistance to the base plan.

My first exposure to Guam was in 1977, when I made a very brief stay over on my way to Ifalik atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia (then still a UN Trust Territory) for ethnographic fieldwork that was part of my graduate training as an anthropologist. My miseducation up to that point had been profound: I could come to that nation of islands without having first learned – through many years of education in US schools – the hard facts about the colonial status of the area to which I was coming. My anthropological training back then focused, as most such programs did, on the beauty of indigenous ideas and rituals, of kinship systems and healing practices. However helpful attention to such things was toward the goal of a humane and anti-racist understanding of the world, the cultural worlds that anthropology had tried to document were treated as if they occurred in a vacuum, outside of the influence of powerful economic and political forces and outside of history.

My miseducation led me to be surprised when my initial permission to travel to Ifalik was granted not by Chamorros and Carolinians, but by US bureaucrats, then operating as Trust Territory officials. I only then came to realize what this all actually meant – that Ifalik, like Guam, has had an deeply colonial history, and that the lives the people there have led were in some ways of their own creative making and in other ways they were the result of choices by people in other remote locations, most recently in Tokyo and Washington, DC.

Such is no less true now than it was in 1950 or 1977. It is the reason the people of Guam today wait to hear exactly how many more acres of their land will be taken for military purposes, how many tens of thousands of new people and new vehicles will be visited on the island, how many over flights and aircraft carrier visits, and toxic trickles or spills will be visited upon them. It is why they wait, not for rent payments for the land, but to hear whether there will be some US federal dollars allocated to cover some percentage of the externalized costs of the increased tempo of military operations on the island. That is Guam’s colonial history and colonial situation. It is colonial even as many of Guam’s residents take their US citizenship seriously and want to make claims to full citizenship on the foundation of the limited citizenship they now have. It is colonial even as Guam’s many military members – those born on Guam and those born in the 50 United States – can and do see themselves as doing their duty to the US civilian leadership who deploy them to bases here and around the world. It is colonial even as many of Guam’s citizens have been acting in the faith that they should be able to make and are making their own choices about whether Guam becomes even more of a battleship or not. But social science will call it nothing more than colonial when a people have not historically chosen their most powerful leaders and have been told to background their own national identity in favor of that of the power which has ultimate rule. The US presence in Guam is properly called imperial because the US is an empire in the strict sense of the term as used by historians and other social analysts of political forms.

Besides colonialism, another concept relevant to Guam’s situation is militarization. It refers to an increase in labor and resources allocated to military purposes and the shaping of other institutions in synchrony with military goals. It involves a shift in societal beliefs and values in ways that legitimate the use of force (Ferguson 2009). It helps describe the process by which 14 year olds are in uniform and carrying proxy rifles in JROTC units in all of Guam’s schools, why a fifth to a quarter of high school graduates enter the military, and why the identity of the island has over time shifted from a land of farmers to a land of war survivors to a land of loyal Americans to a land that is, proudly, “the Tip of the Spear,” that is, a land that is a weapon. This historical change – the process of militarization or military colonization – has been visible to some, but more often, hidden in plain sight.

US global military basing system

Guam’s military bases are part of the expansive US military basing system around the world and on the US mainland. That system is vast in scale and impact and has a particular if contentious rationale. It is important to examine what it means to live next to military facilities for several reasons:

(1) To study them with the tools of anthropology and the perspective of social science allows us to question the common sense about them and to see invisible processes.

(2) Like most social phenomena, bases are often hidden in plain sight. They are normalized from day to day, but are partially denormalized when they grow or shrink. Even then, much remains invisible and accepted as the natural order of things.

(3) Like social phenomena in which power is involved, their effects can be systematically hidden by advertising, fear, and public relations work.

Military base communities are in many ways as distinctive sociologically and anthropologically as the military bases they sit next to, because they respond in almost every way to the presence of those bases. They are not simply independent neighbors, but over time become conjoined, although one is always much more powerful than the other.

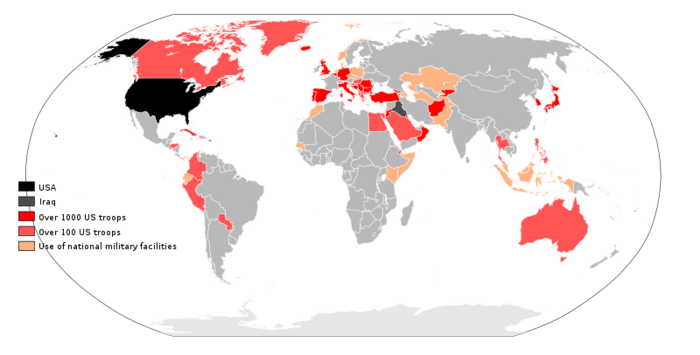

Officially, as of late 2008 (the last date for which the DoD has made such data public) over 150,000 troops and 95,000 civilian employees are massed in 837 US military facilities in 45 countries and territories, excluding Iraq and Afghanistan. There, the US military owns or rents 720,000 acres of land, and owns, rents or uses 60,000 buildings and manages structures valued at $145 billion. 4742 bases are located in the domestic United States. These official numbers are quite misleading as to the scale of US overseas military basing, however. That is because they not only exclude the massive buildup of new bases and troop presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also secret or unacknowledged facilities in Israel, Kuwait, the Philippines and many other places.

U.S. military bases worldwide

Large sums of money are involved in their building and operation. $2 billion in military construction money has been expended in only three years of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Just one facility in Iraq, Balad Air Base, houses 30,000 troops and 10,000 contractors, and extends across 16 square miles with an additional 12 square mile “security perimeter.” The Guam build-up has been projected to cost between $10 and $15 billion, with much of that amount in contracts going to businesses in the U.S., Japan, South Korea, and, less significantly, Guam itself.

These military facilities include sprawling Army bases with airfields and McDonalds and schools, and small listening posts. They include artillery testing ranges, and berthed aircraft carriers.2 While the bases are literally barracks and weapons depots and staging areas for war making and ship repair facilities and golf courses and basketball courts, they are also political claims, spoils of war, arms sales showrooms, toxic industrial sites, laboratories for cultural (mis)communication, and collections of customers for local shops, services, bars, and prostitution.

The environmental, political, and economic impact of these bases is enormous. While some people benefit from the coming of a base, at least temporarily, most communities and many within them pay a high price: their farm land taken for bases, their bodies attacked by cancers and neurological disorders because of military toxic exposures, their neighbors imprisoned, tortured and disappeared by the autocratic regimes that survive on US military and political support given as a form of tacit rent for the bases.

The count of US military bases should also include the eleven aircraft carriers in the US Navy’s fleet, each of which it refers to as “four and a half acres of sovereign US territory.” These moveable bases and their land-based counterparts are just the most visible part of the larger picture of US military presence overseas. This picture of military access includes (1) US military training of foreign forces, often in conjunction with the provision of US weaponry, (2) joint exercises meant to enhance US soldiers’ exposure to a variety of operating environments from jungle to desert to urban terrain and interoperability across national militaries, and (3) legal arrangements made to gain overflight rights and other forms of ad hoc use of others’ territory as well as to preposition military equipment there. In all of these realms, the US is in a class by itself, no adversary or ally maintaining anything comparable in terms of its scope, depth and global reach.

These three elements come with problems: The training programs strengthen the power of military forces in relation to other sectors within those countries, sometimes with fragile democracies. Fully 38 percent of those countries with US basing were cited in 2002 for their poor human rights record (Lumpe 2002:16). The exercises have sometimes been provocative to other nations, and in some cases have become the pretext for substantial and permanent positioning of troops; in recent years, for example, the US has run approximately 20 exercises annually on Philippine soil. Recently (July, 2010) announced joint US-South Korean military exercises in the Yellow Sea, just off the coast of China, have produced strong protest from it and arguably will lead to increases in its military spending.

The attempt to gain access has also meant substantial interference in the affairs of other nations: for example, lobbying to change the Philippine and Japanese constitutions to allow, respectively, foreign troop basing, US nuclear weapons, and a more-than-defensive military in the service of US wars, in the case of Japan. US military and civilian officials are joined in their efforts by intelligence agents passing as businessmen or diplomats; in 2005, the US Ambassador to the Philippines created a furor by mentioning that the US has 70 agents operating in Mindanao alone.

Given the sensitivity about sovereignty and the costs of having the US in their country, elaborate bilateral negotiations result in the exchange of weapons, cash, and trade privileges for overflight and land use rights. Less explicitly, but no less importantly, rice import levels or immigration rights to the US or overlooking human rights abuses have been the currency of exchange (Cooley 2008).

Bases are the literal and symbolic anchors, and the most visible centerpieces, of the U.S. military presence overseas. To understand where those bases are and how they are being used is essential for understanding the United States’ relationship with the rest of the world, the role of coercion in it, and its political economic complexion. We can begin by asking why this empire of bases was established in the first place, how the bases are currently configured around the world and how that configuration is changing.

What are bases for?

Foreign military bases have been established throughout the history of expanding states and warfare. They proliferate where a state has imperial ambitions, either through direct control of territory or through indirect control over the political economy, laws, and foreign policy of other places. Whether or not it recognizes itself as such, a country can be called an empire when it projects substantial power with the aim of asserting and maintaining dominance over other regions. Those policies succeed when wealth is extracted from peripheral areas, and redistributed to the imperial center. Empires, then, have historically been associated with a growing gap between the wealth and welfare of the powerful center and the regions it dominates. Alongside and supporting these goals has often been elevated self-regard in the imperial power, or a sense of racial, cultural, or social superiority.

The descriptors empire and imperialism have been applied to the Romans, Incas, Mongols, Persians, Portuguese, Spanish, Ottomans, Dutch, British, Germans, Soviets, Chinese, Japanese, and Americans, among others. Despite the striking differences between each of these cases, each used military bases to maintain some forms of rule over regions far from their center. The bases eroded the sovereignty of allied states on which they were established by treaty; the Roman Empire was accomplished not only by conquest, but also “by taking her weaker [but still sovereign] neighbors under her wing and protecting them against her and their stronger neighbors… The most that Rome asked of them in terms of territory was the cessation, here and there, of a patch of ground for the plantation of a Roman fortress” (Magdoff et al. 2002).

What have military bases accomplished for these empires through history? Bases are usually presented, above all, as having rational, strategic purposes; the imperial power claims that they provide forward defense for the homeland, supply other nations with security, and facilitate the control of trade routes and resources. They have been used to protect non-economic actors and their agendas as well – missionaries, political operatives, and aid workers among them. Bases have been used to control the political and economic life of the host nation. Politically, bases serve to encourage other governments’ endorsement of the empire’s military and other foreign policies. Corporations and the military itself as an organization have a powerful stake in bases’ continued existence regardless of their strategic value (Johnson 2004).

Alongside their military and economic functions, bases have symbolic and psychological dimensions. They are highly visible expressions of a nation’s will to status and power. Strategic elites have built bases as a visible sign of the nation’s standing, much as they have constructed monuments and battleships. So, too, contemporary US politicians and the public have treated the number of their bases as indicators of the nation’s hyperstatus and hyperpower. More darkly, overseas military bases can also be seen as symptoms of irrational or untethered fears, even paranoia, as they are built with the long-term goal of taming a world perceived to be out of control. Empires frequently misperceive the world as rife with threats and themselves as objects of violent hostility from others. Militaries’ interest in organizational survival has also contributed to the amplification of this fear and imperial basing structures as the solution as they “sell themselves” to their populace by exaggerating threats, underestimating the costs of basing and war itself, as well as understating the obstacles facing preemption and belligerence (Van Evera 2001).

As the world economy and its technological substructures have changed, so have the roles of foreign bases. By 1500, new sailing technologies allowed much longer distance voyages, even circumnavigational ones, and so empires could aspire to long networks of coastal naval bases to facilitate the control of sea lanes and trade. They were established at distances that would allow provisioning the ship, taking on fresh fruit that would protect sailors from scurvy, and so on. By the 21st century, technological advances have at least theoretically eliminated many of the reasons for foreign bases, given the possibilities of in transit refueling of jets and aircraft carriers, the nuclear powering of submarines and battleships, and other advances in sea and airlift of military personnel and equipment. Bases have, nevertheless, continued their ineluctable expansion.

States that invest their people’s wealth in overseas bases have paid direct as well as opportunity costs, whose consequences in the long run have usually been collapse of the empire. In The Rise and Fall of Great Powers, Kennedy notes that previous empires which established and tenaciously held onto overseas bases inevitably saw their wealth and power decay as they chose “to devote a large proportion of its total income to ‘protection,’ leaving less for ‘productive investment,’ it is likely to find its economic output slowing down, with dire implications for its long-term capacity to maintain both its citizens’ consumption demands and its international position” (Kennedy 1987:539).

Nonetheless, U.S. defense officials and scholars have continued to argue that bases lead to “enhanced national security and successful foreign policy” because they provide “a credible capacity to move, employ, and sustain military forces abroad,” (Blaker 1990:3) and the ability “to impose the will of the United States and its coalition partners on any adversaries.” This belief helps sustain the US basing structure, which far exceeds any the world has seen: this is so in terms of its global reach, depth, and cost, as well as its impact on geopolitics in all regions of the world, particularly the Asia-Pacific.

A short history of US basing

After consolidation of continental dominance, there were three periods of expansive global ambition in US history beginning in 1898, 1945, and 2001. Each is associated with the acquisition of significant numbers of new overseas military bases. The Spanish-American war resulted in the acquisition of a number of colonies, but the US basing system was far smaller than that of its political and economic peers including many European nations as well as Japan. In the next four decades US soldiers were stationed in just 14 bases, some quite small, in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, and the Virgin Islands, but also, already, extending across the Pacific to Hawaii, Midway, Wake, and Guam, the Philippines, Shanghai, two in the Aleutians, American Samoa, and Johnston Island (Harkavy 1982). This small number was the result in part of a strong anti-statist and anti-militarist strain in US political culture (Sherry 1995). From the perspective of many in the US through the inter-war period, to build bases would be to risk unwarranted entanglement in others’ conflicts.

England had the most during this period, with some countries with large militaries and even some with expansive ambitions having relatively few overseas bases; Germany and the Soviet Union had almost none. But the attempt to acquire such bases would be a contributing cause of World War II (Harkavy 1989:5).

From 14 bases in 1938, by the end of WW II, the United States had built or acquired an astounding 30,000 installations large and small in approximately 100 countries. While this number contracted significantly, it went on to provide the sinews for the rise to global hegemony of the United States (Blaker 1990:22). Certain ideas about basing and what it accomplished were to be retained from World War II as well, including the belief that “its extensive overseas basing system was a legitimate and necessary instrument of U.S. power, morally justified and a rightful symbol of the U.S. role in the world” (Blaker 1990:28).

Nonetheless, pressure came from Australia, France, and England, as well as from Panama, Denmark and Iceland, for return of bases in their own territory or colonies, and domestically to demobilize the twelve million man military (a larger military would have been needed to maintain the vast basing system). More important than the shrinking number of bases, however, was the codification of US military access rights around the world in a comprehensive set of legal documents. These established security alliances with multiple states within Europe (NATO), the Middle East and South Asia (CENTO), and Southeast Asia (SEATO), and they included bilateral arrangements with Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. These alliances assumed a common security interest between the United States and other countries and were the charter for US basing in each place. Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs) were crafted in each country to specify what the military could do; these usually gave US soldiers broad immunity from prosecution for crimes committed and environmental damage created. These agreements and subsequent base operations have usually been shrouded in secrecy.

In the United States, the National Security Act of 1947, along with a variety of executive orders, instituted what can be called a second, secret government or the “national security state”, which created the National Security Agency, National Security Council, and Central Intelligence Agency and gave the US president expansive new imperial powers. From this point on, domestic and especially foreign military activities and bases were to be heavily masked from public oversight (Lens 1987). Many of those unaccountable funds then and now go into use overseas, flowing out of US embassies and military bases. Including use to interfere in the domestic affairs of nations in which it has had or desired military access, including attempts to influence votes on and change anti-nuclear and anti-war provisions in the Constitutions of the Pacific nation of Belau and of Japan.

Nonetheless, over the second half of the 20th century, the United States was either evicted or voluntarily left bases in dozens of countries.3 Between 1947 and 1990, the US was asked to leave bases in France, Yugoslavia, Iran, Ethiopia, Libya, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Algeria, Vietnam, Indonesia, Peru, Mexico, and Venezuela. Popular and political objection to the bases in Spain, the Philippines, Greece, and Turkey in the 1980s enabled those governments to negotiate significantly more compensation from the United States. Portugal threatened to evict the US from important bases in the Azores, unless it ceased its support for independence for its African colonies, a demand with which the US complied.4 In the 1990s and later, the US was sent packing, most significantly, from the Philippines, Panama, Saudi Arabia, Vieques, and Uzbekistan (Simbulan 1985).

At the same time, remarkable numbers of new US bases were newly built (241) after 1947 in remarkable numbers in the Federal Republic of Germany, as well as in Italy, Britain, and Japan (Blaker 1990:45). The defeated Axis powers continued to host the most significant numbers of US bases: at its height, Japan was peppered with 3,800 US installations.

As battles become bases, so bases become battles; the bases in East Asia acquired in the Spanish American War and in World War II, such as Guam, Okinawa and the Philippines, became the primary sites from which the United States waged war on Vietnam. Without them, the costs and logistical obstacles for the US would have been immense. The number of bombing runs over North and South Vietnam required tons of bombs to be unloaded, for example, at the Naval Station in Guam, stored at the Naval Magazine in the southern area of the island, and then shipped to be loaded onto B-52s at Andersen Air Force Base every day during years of the war. The morale of ground troops based in Vietnam, as fragile as it was to become through the latter part of the 1960s, depended on R & R at bases throughout East and Southeast Asia which allowed them to leave the war zone and be shipped back quickly and inexpensively for further fighting (Baker 2004:76). In addition to the bases’ role in fighting these large and overt wars, they facilitated the movement of military assets to accomplish the over 200 military interventions carried out by the US in the course of the Cold War period (Blum 1995).

While speed of deployment is framed as an important continued reason for forward basing, equally important is that troops could be deployed anywhere in the world from US bases without having to touch down en route. In fact, US soldiers are being increasingly billeted on US territory, including such far-flung areas as Guam, which is presently slated for a larger buildup for this reason as well as to avoid the political and other costs of foreign deployment.

With the will to gain military control of space, as well as gather intelligence, the US over time, especially in the 1990s, established a large number of new military bases to facilitate the strategic use of communications and space technologies. Military R&D (the Pentagon spent over $52 billion in 2005 and employed over 90,000 scientists) and corporate profits to be made in the development and deployment of the resulting technologies have been significant factors in the growing numbers of technical facilities on foreign soil. These include such things as missile early-warning radar, signals intelligence, space tracking telescopes and laser sources, satellite control, downwind air sampling monitors, and research facilities for everything from weapons testing to meteorology. Missile defense systems and network centric warfare increasingly rely on satellite technology and drones with associated requirements for ground facilities. These facilities have often been established in violation of arms control agreements such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty meant to limit the militarization of space.

The assumption that US bases served local interests in a shared ideological and security project dominated into the 1960s: allowing base access showed a commitment to fight Communism and gratitude for US military assistance. But with decolonization and the US war in Vietnam, such arguments began to lose their power, and the number of US overseas bases declined from an early 1960s peak. Where access was once automatic, many countries now had increased leverage over what the US had to give in exchange for basing rights, and those rights could be restricted in a variety of important ways, including through environmental and other regulations. The bargaining chips used by the US were increasingly sophisticated weapons, as well as rent payments for the land on which bases were established.5 These exchanges were often linked with trade and other kinds of agreements, such as access to oil and other raw materials and investment opportunities (Harkavy 1982:337). They also have had destabilizing effects on regional arms balances, particularly when advanced weaponry is the medium of exchange. From the earlier ideological rationale for the bases, global post-war recovery and decreasing inequality between the US and countries – mostly in the global North – that housed the majority of US bases, led to a more pragmatic or economic grounding to basing negotiations, albeit often thinly veiled by the language of friendship and common ideological bent. The 1980s saw countries whose populations and governments had strongly opposed US military presence, such as Greece, agree to US bases on their soil only because they were in need of the cash, and Burma, a neutral but very poor state, entered negotiations with the US over basing troops there (Harkavy 1989:4-5).

The third period of accelerated imperial ambition began in 2000, with the election of George Bush and the ascendancy to power of a group of leaders committed to a more aggressive and unilateral use of military power, their ability to expand the scope of US power increased by the attacks of 9/11. They wanted “a network of ‘deployment bases’ or ‘forward operating bases’ to increase the reach of current and future forces” and focused on the need for bases in Iraq. While the unresolved conflict with Iraq provides the immediate justification, the need for a substantial American force presence in the Gulf transcends the issue of the regime of Saddam Hussein. This plan for expanded US military presence around the world has been put into action, particularly in the Middle East, the Russian perimeter, and, now, Africa.

New U.S. Military Bases, 1991-2003

Pentagon transformation plans result in the design of US military bases to operate ever more as offensive, expeditionary platforms from which to project military capabilities quickly anywhere. Where bases in Korea, for example, were once meant primarily to defend South Korea from attack from the north, they are now, like bases everywhere, project power in many directions and serve as stepping stones to battles far from themselves. The Global Defense Posture Review of 2004 announced these changes, focusing not just on reorienting the footprint of US bases away from Cold War locations, but on grounding imperial ambitions through remaking legal arrangements that support expanded military activities with other allied countries and prepositioning equipment in those countries to be able to “surge” military force quickly, anywhere.

The Department of Defense currently distinguishes three types of military facilities. “Main operating bases” are those with permanent personnel, strong infrastructure, and often including family housing, such as Kadena Air Base in Japan and Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany. “Forward operating sites” are “expandable warm facilit[ies] maintained with a limited U.S. military support presence and possibly prepositioned equipment,” such as Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras (US Defense Department 2004:10). Finally, “cooperative security locations” are sites with few or no permanent US personnel, which are maintained by contractors or the host nation for occasional use by the US military, and often referred to as “lily pads.” In Thailand, for example, U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield has been used extensively for US combat runs over Iraq and Afghanistan. Others are now cropping up around the world, especially throughout Africa, as in Dakar, Senegal where facilities and use rights have been newly established.

Are Guam’s bases domestic or overseas bases? Are there racial underpinnings to the differences in how Guam’s basing is handled?

The history just recounted mostly refers to US bases on other countries’ sovereign soil. Is Guam’s situation anomalous? Is Guam’s Andersen AFB a domestic base or a foreign base? As Guam is a US territory, it is neither a fully incorporated part of the US nor a free nation. The island’s license plate, which notes it is “Where America’s Day Begins,” also reads, “Guam USA.” This expresses the wish of some, rather than the reality. It perhaps would better read, Guam, US sort of A. International legal norms make the status clear, however. Guam is a colony, and primarily a military colony, in keeping with the idea that the US’ imperial history, especially in the second half of the 20th century, has been a military colonialism around the world.

Guam’s status shifts by context, however. The DoDs Base Structure Report places Guam and its 39,287 “owned” acres (39 percent of the island’s territory) between Georgia (560,799 acres) and Hawaii (175,911 acres). No Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) regulates the US forces on Guam, and as far as I know, the DoD does not need to report each day to the government of Guam on how many soldiers have been brought in or sent out of Guam, nor is it negotiating with Guam about its plans to grow its bases on Guam.

Map of US military bases on Guam (1991)

One very important and empirical index of the degree to which Guam’s bases are foreign or domestic is the quality of care that has been taken with its environment and health (Castro 2007). Overseas bases have repeatedly inflicted environmental devastation. Unexploded ordnance killed 21 people in Panama before the US was evicted and continues to threaten communities nearby. In Germany, industrial solvents, firefighting chemicals, and varieties of waste have ruined ecological systems near some US bases. The Koreans are finding extremely high levels of military toxins in bases returned to them by the US from near the DMZ. Ebeye atoll suffers severe water quality and quantity problems due to the US military presence (Soroko 2006).

While Guam’s environment has been treated carelessly through the years, environmental standards have not been high enough for domestic US bases either. Fort Bragg in North Carolina, for example, engaged in outdoor burning of very large numbers of its unwanted, old wooden barracks at one point in the 1970s, and an ancient water treatment plant was used on Fort Bragg up until quite recently. One can also point to the US Army Corps of Engineers’ Formerly Used Defense Sites whose cleanup would be so expensive that they are termed “national sacrifice zones,” or permanent no man’s lands by some.

But activists have long considered the environmental and judicial standards that are negotiated into each country’s SOFA as an index of how much respect their country is accorded. It is possible to measure the quantity of toxins variously introduced into the environment of Guam, Germany, the Philippines, California, and North Carolina, for example. The broad differences in that quantity roughly occur on a scale that appears quite racial, with the US mainland at the top, Germany next, and the Philippines and Guam at the bottom. If Guam’s political status were truly domestic, we might expect Guam to look more like the mainland in terms of how the environment has been cared for. It does not.

But the internal racial history of the US itself demonstrates that the military base has been a booby prize for many of the internally colonized in the US as well: the distinction between domestic and foreign bases has been blurry on the mainland as well. All domestic military bases are in fact, of course, built on Native American land, and even after that land was taken, the bases were often intentionally sited on land inhabited by poor white, black and Indian farmers. Thousands of them lost their land in North Carolina alone in the buildup to WW II (Lutz 2001).

And there, too, we can ask, as we ask on Guam, who benefited then and who benefits now from base building and base buildups? What costs are externalized and borne by others? And how has a rhetoric of national security over all contributed to the notion that the military can be and should be excepted from environmental protection standards?

The externalized costs of bases

The people of Guam have been engaged in a several year exercise of trying to detail the impact of military bases in order to gain some relief from the expected continuing externalization of the physical and social costs of military basing onto the people of Guam. Among the health and environmental issues pertaining to base expansion are the long term maintenance of roads, the stressed and declining water supply, and the likely upswing in crime rates.

In this final section, the economic impact of bases is examined, as this has been crucial in Guam and elsewhere for the arguments made for military expansion. Obviously the health and wellbeing of people affected by military basing are crucial, but the economic effects have been the primary thing that people in many base communities have focused on. This is so for two reasons. The first is that the military itself publicizes its arrival or expansion as an economic boon, noting the dollars brought in via soldier’s salaries, civilian work on post, and construction and other sub-contracts that could provide jobs. So the First Hawaiian Bank published a Guam Economic Forecast that claimed “The military expansion is anticipated to benefit Guam’s economy in the amount of $1.5 billion per year once the process begins.”6

The second reason for the economic focus is that they appear overall to be positive, unlike the environmental, sovereignty, cultural, crime, and noise effects. But one of the reasons they look positive is because the powerful benefit and have the resources to convince others that they, too, benefit even when they palpably do not. Moreover, the military has large numbers of personnel, military and civilian, doing public relations work with media and communities to make their case for simple economic positives. In addition, those locals who are most likely to benefit financially have the funding and motivation to do similar public relations work. For example, the Chamber of Commerce funded a 2008 survey that found that “71 per cent of Guam residents supported an increase in the United States military presence, with nearly 80 per cent of the view that the increasing military presence would result in additional jobs and tax revenue; according to the poll, 60 per cent felt the additional Marines on the island would have a positive effect and would ultimately improve the island’s quality of life.”7 This poll was as much an attempt to create reality as to reflect it. It builds on an existing cultural narrative, one that is purchased with media time and power, a narrative that says “you will all benefit.”

What are the economic effects of bases? Three major factors can be identified. First, the economic effects are primarily redistributional rather than generative (unlike, for example, manufacturing or education jobs). Certain sectors atrophy and others grow in military districts, often in very strong fluctuations. In 2007 in Guam, for example, “While employment in manufacturing, transportation and public utilities and retail trade decreased, increases were seen for jobs in the service sector and public sector; with the construction sector experiencing the largest increase, that is, 1,450 jobs, or 35 per cent.”8 Usually, retail jobs are the main type of work created around military bases. Unfortunately, those jobs pay less than any other category of work, accelerating the growth of inequality in military communities.

Second, the military is a highly toxic industrial operation and it externalizes many of its costs of operation to the communities that host it and serve it. These costs include such things as environmental waste, PTSD in returning war veterans and high rates of domestic violence, rapid deterioration of roads and other public amenities, and, in many communities, decline in human capital development of populations that have gone into the military (Lutz and Bartlett 1995, Lutz 2001). JROTC, for example, only appears to add resources to school districts while it in fact draws on significant local education resources, while serving as recruiting devices. The math on these costs – the subtraction from the general welfare and general public funds – is rarely done.

Finally, military economies are volatile. While the “war cycle” is different than the business cycle, it also has booms and busts. For example, businesses in military personnel cities like Fayetteville, North Carolina regularly go under when service members are deployed to US war zones. Any major deployment from Guam’s bases can be expected to significantly harm local enterprise dependent on military business. Moreover, a volatile real estate market catering to foreign military personnel sends property prices spiralling and forces local working families into more substandard housing.

Conclusion

There are legal questions in the Guam military buildup as well. In her testimony before the UN Committee of 24 in 2008, Sabina Flores Peres referred to the extremity of “the level and grossness of the infraction” of the UN Charter by the US in its further militarization of the island. This is not hyperbole, because Guam’s militarization is objectively more extreme in its concentration than that found virtually anywhere else on earth. There are only a few other areas that are in similar condition – all, not coincidentally islands such as Okinawa, Diego Garcia, and, in the past, Vieques, Puerto Rico (see e.g., Inoue 2004, Yoshida 2010 and McCaffrey 2002). This was the product of an island strategy for the US Navy, developed in the face of decolonization and anxieties about the fate of continental US bases in that context in the 1950s and 1960s (Vine 2009).

Guam, objectively, has the highest ratio of US military spending and military hardware and land takings from indigenous populations of any place on earth. Here there might have been rivals in Diego Garcia or in some areas of the continental US if the US had not forcibly removed those indigenous landowners altogether or onto the equivalent of reservations, something the US had hoped to do in Guam as far back as 1945. The level and grossness of the infraction has to do with the racial hierarchy that fundamentally guides the US in its “negotiations” with other peoples over the siting of its military bases and the treatment they are accorded once the US settles in. As the military budget suddenly and intensely comes under scrutiny in the United States in the summer of 2010 during severe economic crisis, the hope must be that the project of building yet more military facilities on Guam will hit the chopping block. As a human rights issue, however, the US treatment of Guam’s people should have no price tag.

Catherine Lutz is the Thomas J. Watson Jr. Family Professor in Anthropology and International Studies at the Watson Institute for International Studies at Brown University. She is the author of The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Posts and (with elin o’Hara slavick, Carol Mayvor and Howard Zinn), Bomb after Bomb: A Violent Cartography.

Recommended citation: Catherine Lutz, “US Military Bases on Guam in Global Perspective,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 30-3-10, July 26, 2010.

References

Aguon, Julian. (2006) The Fire This Time: Essays on Life Under U.S. Occupation. (Tokyo: Blue Ocean Press).

Baker, Anni (2004) American Soldiers Overseas: The Global Military Presence (Westport, CT: Praeger).

Blaker, James R. (1990) United States Overseas Basing: An Anatomy of the Dilemma (New York: Praeger).

Blum, William (1995) Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions since World War II (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press).

Castro, Fanai (2007) Health Hazards: Guam. In Outposts of Empire, Sarah Irving, Wilbert van der Zeijden, and Oscar Reyes, eds. (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute).

Cooley, Alexander. Base Politics: Democratic Change and the U.S. Military Overseas. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Department of Defense Base Structure Report Fiscal Year 2009 Baseline (A Summary of DOD’s Real Property Inventory). Link.

Diaz, Vicente (2001) Deliberating Liberation Day: Memory, Culture and History in Guam. In Perilous Memories: the Asia Pacific War(s). Takashi Fujitani, Geoff White and Lisa Yoneyami, eds. (Durham: Duke University Press).

Erickson, Andrew S. and Mikolay, Justin D. (2006) A Place and a Base: Guam and the American Presence in East Asia. In Reposturing the Force: U.S. Overseas Presence in the 21st Century. Carnes Lord, ed. (Newport: Naval War College).

Harkavy, Robert E. (1982) Great Power Competition for Overseas Bases: The Geopolitics of Access Diplomacy (New York: Pergamon Press).

—— (1989) Bases Abroad: The Global Foreign Military Presence (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Inoue, Masamichi S. (2004) ‘“We Are Okinawans But of a Different Kind”: New/Old Social Movements and the U.S. Military in Okinawa,’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 45, No. 1.

Johnson, Chalmers (2004) The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic (New York: Metropolitan).

Kennedy, Paul M. (1987) The Rise and Fall of Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500-2000 (New York: Random House).

Lens, Sidney (1987) Permanent War: The Militarization of America (New York: Schocken).

Lumpe, Lora (2002) U.S. Foreign Military Training: Global Reach, Global Power, and Oversight Issues. Foreign Policy in Focus Special Report, May.

Lutz, Catherine (2001) Homefront: A Military City and the American 20th Century (Boston: Beacon Press).

Lutz, Catherine and Lesley Bartlett (1995) Making Soldiers in the Public Schools: An Analysis of the Army JROTC Curriculum. (Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee).

Magdoff, Harry, Foster, John Bellamy, McChesney, Robert W. and Sweezy, Paul (2002) U.S. Military Bases and Empire, The Monthly Review Vol. 53, No. 10.

McCaffrey, Katherine (2002) Military Power and Popular Protest: The U.S. Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press).

Natividad, LisaLinda and Gwyn Kirk (2010) “Fortress Guam: Resistance to US Military Mega-Buildup,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, May 10, 2010, link.

Sherry, Michael S. (1995) In the Shadow of War: The United States Since the 1930’s (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Simbulan, Roland (1985) The Bases of our Insecurity: A Study of the U.S. Military Bases in the Philippines (Manila, Philippines: BALAI Fellowship).

Soroko, Jennifer (2006) ‘Water at the intersection of militarization, development, and democracy on Kwajalein Atoll, in the Republic of the Marshall Islands’. MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, Brown University.

US Defense Department (2004) Strengthening U.S. Global Defense Posture, Report to Congress (Washington, D.C.).

Van Evera, Stephen (2001) Militarism (Cambridge, MA: MIT). Available [online] here. Date last accessed July 23, 2010.

Vine, David. (2009) Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yoshida, Kensei (2010) Okinawa and Guam: In the Shadow of U.S. and Japanese “Global Defense Posture,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, link.

Notes

1 This paper is an updated and revised version of an invited Presidential Lecture given at the University of Guam on April 14, 2009. Portions appeared in the Introduction to The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against US Military Posts. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

2 The major concentrations of U.S. sites outside those war zones as of 2007 were in South Korea, with 106 sites and 29,000 troops, Japan with 130 sites and 49,000 troops, most concentrated in Okinawa, and Germany with 287 sites and 64,000 troops. Guam with 28 facilities has nearly 6,600 airmen and soldiers and is slated to radically expand over the next several years (Base Structure Report FY2007).

3 Between 1947 and 1988, the U.S. left 62 countries, 40 of them outside the Pacific Islands (Blaker 1990:34).

4 Luis Nuno Rodrigues, ‘Trading “Human Rights” for “Base Rights”: Kennedy, Africa and the Azores’, Ms. Possession of the author, March 2006.

5 Harkavy (1982:337) calls this the “arms-transfer-basing nexus” and sees the U.S. weaponry as having been key to maintaining both basing access and control over the client states in which the bases are located. Granting basing rights is not the only way to acquire advanced weaponry, however. Many countries purchased arms from both superpowers during the Cold War, and they are less likely to have US bases on their soil.

6 Economic Forecast — Guam Edition 2006-2007, First Hawaiian Bank, pp. 8-9.

7 Link, 18 February 2008.

8 Link, September 2007, Current Employment Report.