Africa: Land and Seed Laws Under Attack, Battle for Control of Land, Water, Seeds, Minerals, Forests, Oil

“The 50 million people that the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition claims to be lifting out of poverty will only be allowed to escape poverty and hunger if they abandon their traditional rights and practices and buy their life saving seeds every year from the corporations lined up behind the G8.” – Tanzania Organic Agriculture Movement, member of AFSA, September 2014

A battle is raging for control of resources in Africa – land, water, seeds, minerals, ores, forests, oil, renewable energy sources. Agriculture is one of the most important theatres of this battle. Governments, corporations, foundations and development agencies are pushing hard to commercialise and industrialise African farming.

Many of the key players are well known.1 They are committed to helping agribusiness become the continent’s primary food commodity producer. To do this, they are not only pouring money into projects to transform farming operations on the ground − they are also changing African laws to accommodate the agribusiness agenda.

Privatising both land and seeds is essential for the corporate model to flourish in Africa. With regard to agricultural land, this means pushing for the official demarcation, registration and titling of farms. It also means making it possible for foreign investors to lease or own farmland on a long-term basis. With regard to seeds, it means having governments require that seeds be registered in an official catalogue in order to be traded. It also means introducing intellectual property rights over plant varieties and criminalising farmers who ignore them. In all cases, the goal is to turn what has long been a commons into something that corporates can control and profit from.

This survey aims to provide an overview of just who is pushing for which specific changes in these areas – looking not at the plans and projects, but at the actual texts that will define the new rules. It was not easy to get information about this. Many phone calls to the World Bank and Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) offices went unanswered. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) brushed us off. Even African Union officials did not want to answer questions from – and be accountable to – African citizens doing this inventory. This made the task of coming up with an accurate, detailed picture of what is going on quite difficult. We did learn a few things, though:

• While there is a lot of civil society attention focused on the G8’s New Alliance for Food and Nutrition, there are many more actors doing many similar things across Africa. Our limited review makes it clear that the greatest pressure to change land and seed laws comes from Washington DC – home to the World Bank, USAID and the MCC.

• Land certificates – which should be seen as a stepping stone to formal land titles – are being promoted as an appropriate way to “securitise” poor peoples’ rights to land. But how do we define the term “land securitisation”? As the objective claimed by most of the initiatives dealt with in this report, it could be understood as strengthening land rights. Many small food producers might conclude that their historic cultural rights to land – however they may be expressed – will be better recognised, thus protecting them from expropriation. But for many governments and corporations, it means the creation of Western-type land markets based on formal instruments like titles and leases that can be traded. In fact, many initiatives such as the G8 New Alliance explicitly refer to securitisation of “investors’” rights to land. These are not historic or cultural rights at all: these are market mechanisms. So in a world of grossly unequal players, “security” is shorthand for market, private property and the power of the highest bidder.

• Most of today’s initiatives to address land laws, including those emanating from Africa, are overtly designed to accommodate, support and strengthen investments in land and large scale land deals, rather than achieve equity or to recognise longstanding or historical community rights over land at a time of rising conflicts over land and land resources.

• Most of the initiatives to change current land laws come from outside Africa. Yes, African structures like the African Union and the Pan-African Parliament are deeply engaged in facilitating changes to legislation in African states, but many people question how “indigenous” these processes really are. It is clear that strings are being pulled, by Washington and Europe in particular, to alter land governance in Africa.

• When it comes to seed laws, the picture is reversed. Subregional African bodies – SADC, COMESA, OAPI and the like – are working to create new rules for the exchange and trade of seeds. But the recipes they are applying – seed marketing restrictions and plant variety protection schemes – are borrowed directly from the US and Europe.

• The changes to seed policy being promoted by the G8 New Alliance, the World Bank and others refer to neither farmer-based seed systems nor farmers’ rights. They make no effort to strengthen farming systems that are already functioning. Rather, the proposed solutions are simplified, but unworkable solutions to complex situations that will not work – though an elite category of farmers may enjoy some small short term benefits.

• Interconnectedness between different initiatives is significant, although these relationships are not always clear for groups on the ground. Our attempt to show these connections gives a picture of how very narrow agendas are being pushed by a small elite in the service of globalised corporate interests intent on taking over agriculture in Africa.

• With seeds, which represent a rich cultural heritage of Africa’s local communities, the push to transform them into income-generating private property, and marginalise traditional varieties, is still making more headway on paper than in practice. This is due to many complexities, one of which is the growing awareness of and popular resistance to the seed industry agenda. But the resolve of those who intend to turn Africa into a new market for global agroinput suppliers is not to be underestimated. The path chosen will have profound implications for the capacity of African farmers to adapt to climate change.

This report was drawn up jointly by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) and GRAIN. AFSA is a pan-African platform comprising networks and farmer organisations championing small African family farming based on agro-ecological and indigenous approaches that sustain food sovereignty and the livelihoods of communities. GRAIN is a small international organisation that aims to support small farmers and social movements in their struggles for community-controlled and biodiversity-based food systems.

The report was researched and initially drafted by Mohamed Coulibaly, an independent legal expert in Mali, with support from AFSA members and GRAIN staff. It is meant to serve as a resource for groups and organisations wanting to become more involved in struggles for land and seed justice across Africa or for those who just want to learn more about who is pushing what kind of changes in these areas right now.

Initiatives targeting both land and seed laws

G8 New Alliance on Food Security and Nutrition2

• Initiated by the G8 countries: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, UK and US

• Timeframe: 2012-2022

• Implemented in 10 African countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania

The G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition was launched in 2012 by the eight most industrialised countries to mobilise private capital for investment in African agriculture. To be accepted into the programme, African governments are required to make important changes to their land and seed policies. The New Alliance prioritises granting national and transnational corporations (TNCs) new forms of access and control to the participating countries’ resources, and gives them a seat at the same table as aid donors and recipient governments.3

As of July 2014, ten African countries had signed Cooperative Framework Agreements (CFAs) to implement the New Alliance programme. Under these agreements, these governments committed to 213 policy changes. Some 43 of these changes target land laws, with the overall stated objective of establishing “clear, secure and negotiable rights to land” − tradeable property titles.4

The New Alliance also aims to implement both the Voluntary Guidelines (VGs) on Responsible Land Tenure adopted by the Committee on World Food Security in 2012, and the Principles for Responsible Agriculture Investment drawn up by the World Bank, FAO, IFAD and UN Conference on Trade and Development.5 This is considered especially important since the New Alliance directly facilitates access to farmland in Africa for investors. To achieve this, the New Alliance Leadership Council, a self-appointed body composed of public and private sector representatives, in September 2014 decided to come up with a single set of guidelines to ensure that the land investments made through the Alliance are “responsible” and not land grabs.6

Proposed changes to seed policy are over-simplified, unworkable solutions that will ultimately fail – though an elite group of farmers may enjoy some small short term benefits.

Proposed changes to seed policy are over-simplified, unworkable solutions that will ultimately fail – though an elite group of farmers may enjoy some small short term benefits.As to seeds, all of the participating states, with the exception of Benin, agreed to adopt plant variety protection laws and rules for marketing seeds that better support the private sector. Despite the fact that more than 80% of all seed in Africa is still produced and disseminated through ‘informal’ seed systems (on-farm seed saving and unregulated distribution between farmers), there is no recognition in the New Alliance programme of the importance of farmer-based systems of saving, sharing, exchanging and selling seeds.

African governments are being co-opted into reviewing their seed trade laws and supporting the implementation of Plant Variety Protection (PVP) laws. The strategy is to first harmonise seed trade laws such as border control measures, phytosanitary control, variety release systems and certification standards at the regional level, and then move on to harmonising PVP laws. The effect is to create larger unified seed markets, in which the types of seeds on offer are restricted to commercially protected varieties. The age old rights of farmers to replant saved seed is curtailed and the marketing of traditional varieties of seed is strictly prohibited.

Concerns have been raised about how this agenda privatises seeds and the potential impacts this could have on small-scale farmers. Farmers will lose control of seeds regulated by a commercial system. There are also serious concerns about the loss of biodiversity resulting from a focus on commercial varieties.

Annex 1 details specific plans and actual changes accomplished in each country so far Land legislation and new regulations are being drafted or adopted in most participating countries, with a view to generalising land certificates and eventually land titles. In the seed sector, policy reforms are under way to create a larger role for the private sector as the state pulls out. Finally, farmland is being allocated to foreign and domestic corporations under the banner of both the World Bank and the FAO guidelines on responsible land investing.

The World Bank

The World Bank is a significant player in catalysing the growth and expansion of agribusiness in Africa. It does this by financing policy changes and projects on the ground. In both cases, the Bank targets land and seed laws as key tools for advancing and protecting the interests of the corporate sector.

The Bank’s work on policy aims at increasing agricultural production and productivity through programmes called “Agriculture Development Policy Operations” (AgDPOs).

Understanding AgDPOs

Understanding AgDPOs requires an understanding of Development Policy Operations (DPOs) often used by multilateral development banks in their assistance to countries. A DPO is aimed at helping a country achieve “sustainable poverty reduction” through a programme of policy and institutional actions, such as strengthening public financial management, improving the investment climate, diversifying the economy, etc. This is supposed to represent a shift away from the short-term macroeconomic stabilisation and trade liberalisation reforms of the 1980s and 1990s towards more medium-term institutional reforms.7

The Bank’s use of DPOs in a country is determined in the context of the Country Assistance Strategy, a document prepared by the Bank together with a member country, which describes the Bank’s intervention and the sectors in which it intervenes. The Bank makes funds available when the government being assisted meets three conditions: (1) maintenance of an adequate macroeconomic policy framework, as determined by the Bank with inputs from International Monetary Fund assessments; (2) satisfactory implementation of the overall reform programme for which assistance is needed; and (3) completion of a set of agreed policy and institutional actions.

DPOs work as a series of actions organised around prior actions, triggers and benchmarks. “Prior actions” are are a set of mutually agreed policy and institutional actions that are deemed critical to achieving the objectives of the programme supported by a DPO.They form a legal condition for disbursement which a country agrees to undertake before the Bank approves the loan. Triggers are planned actions in the second or subsequent years of the programme. Benchmarks are the progress markers of the programme, which describe the content and results of the government’s programme in areas monitored by the Bank.

In Africa, AgDPOs support the National Investment Plans through which countries are implementing the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP, adopted in Maputo in 2003). As of July 2014, three countries have been granted World Bank assistance though AgDPOs: Ghana, Mozambique and Nigeria.

Besides financing AgDPOs, the World Bank directly supports agriculture development projects. Some major World Bank projects with land tenure components are presented in Annex 2, with a focus on the legal arrangements developed to make land available for corporate investors. These projects are much more visible than the AgDPOs and their names are well known in each country: PDIDAS in Senegal, GCAP in Ghana, Bagrépole in Burkina. These programmes make large amounts of funding available to enable foreign investors to get large scale access to African farmland – similar to the G8 New Alliance projects but without the political baggage of intergovernmental relationships.

Initiatives targeting land laws

Planting rice in Mali: the common trend, across numerous initiatives to change land laws, is towards titles that will allow communities and small landholders to sell or lease land to investors. (Photo: Devan Wardell/Abt Associates)

Planting rice in Mali: the common trend, across numerous initiatives to change land laws, is towards titles that will allow communities and small landholders to sell or lease land to investors. (Photo: Devan Wardell/Abt Associates) African Union Land Policy Initiative8

The African Union (AU), together with the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), has been spearheading a Land Policy Initiative (LPI) since 2006. Mainly a response to land grabbing on the continent, the LPI is meant to strengthen and change national policies and laws on land. It is funded by the EU, IFAD, UN Habitat, World Bank, France and Switzerland. LPI is expected to become an African Centre on Land Policies after 2016.

The LPI is designed to implement the African Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges, adopted by the AU Summit of Heads of State in July 2009.9 This summit also endorsed the Framework and Guidelines on Land Policy in Africa (F&G) previously adopted by African ministers responsible for agriculture and land in March 2009.10 The Declaration presents African states with a framework to address land issues in a regional context, while the Framework outlines and promotes specific processes to develop and implement land policies at the national level. Neither of these documents go so far as to prescribe what kind of land rights should be promoted (collective vs individual, customary vs formal, etc).

One important undertaking of the LPI is the development of a set of Guiding Principles on Large-Scale Land-Based Investments (LSLBI) meant to ensure that land acquisitions in Africa “promote inclusive and sustainable development”. The Guiding Principles were adopted by the Council of agriculture ministers in June 2014, and are awaiting endorsement by the AU Summit of Heads of States and government.

The Guiding Principles have several objectives, including guiding decision making on land deals (recognising that large scale land acquisitions may not be the most appropriate form of investment); providing a basis for a monitoring and evaluation framework to track land deals in Africa; and providing a basis for reviewing existing large scale land contracts.11

The Guiding Principles draw lessons from global instruments and initiatives to regulate land deals including the Voluntary Guidelines and the Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investments in the Context of Food Security and Nutrition. They also take into account relevant human rights instruments.12

But because the Guiding Principles are not a binding instrument and lack an enforcement mechanism, it is far from certain that they will prove any more effective than other voluntary frameworks on land. They are, however, widely accepted and supported on the continent as the first “African response” to the issue of land grabbing.

ECOWAS (West Africa Land Policies Harmonisation Framework)13

• Proponent: Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

In 2010, ECOWAS, in collaboration with the LPI Secretariat, prepared a single regional framework to harmonise land policies in West Africa. The framework will implement the 2009 AU Declaration on Land Issues and Challenges, taking into account other on-going initiatives in the region, particularly the WAEMU rural land observatory, the FAO’s Voluntary Guidelines, and the LPI Principles on LSLBI. It also endorses the Inter State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS) land charter, a proposed policy framework to establish common principles on land governance in the Sahel and West Africa, expected to be adopted in 2015.14

The main goal of this bid to harmonise land policies is to get a Regional Directive on Rural Lands adopted. This directive will be a legally binding instrument for ECOWAS member states, allowing some flexibility in implementation. The directive will cover land policy development, land conflict management, transboundary issues and how to promote land investments including large scale land deals. According to an ECOWAS report to the 2014 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, a draft of the Directive has already been circulated among Member States for comments.

• New (2014) programme to strengthen land governance in Africa

▪ Ten target countries: Angola, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan and Swaziland

▪ Budget: €33 million

▪ Will apply to 14 ECOWAS member states: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

In April 2014, the EU launched a new programme to improve land governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. It aims to apply principles stemming from the FAO Voluntary Guidelines at the country level. Ten countries are covered by this initiative: Angola, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan and Swaziland. Three of them (Ethiopia, Niger and South Sudan) are also part of the G8 land partnerships described further below.

The programme will be implemented at the national level in partnership with FAO. According to the press release announcing its launch, the programme will:

▪ develop new land registration tools and digital land registry techniques such as satellite images

▪ support local organisations and civil society groups in making farmers “aware” of their land rights

▪ formalise land rights in order to make land use “legitimate”, specifically through the provision of property deeds and relevant documentation to recognise land rights in selected countries

As part of the initiative, FAO will carry out an in-depth assessment of land rights in Somalia, and set up strategies on land management. It will also review the national strategies, policies and legislation required to strengthen of institutions in Kenya.

Parliamentary Assembly of La Francophonie (Assemblée Parlementaire Francophone or APF)

The Parliamentary Assembly of La Francophonie, an association of Parliaments from French-speaking countries, has been working to promote a new construct called the “simplified secure title” (titre simplifié sécurisé, or TSS) to resolve the problem of unclear rights to land for farming or housing in Africa. The TSS is an official land title, but in a simplified form, somewhat like a land certificate. It is the brainchild of Cameroonian notary Abdoulaye Harissou, a member of the International Union of Notaries. Harissou argues that African states must abandon the principle of state ownership of land, and decentralise land administration and management to municipalities. His idea is to have TSS co-exist with the formal land titling system.

TSS would have a clause which precludes sale of land to people from outside of the municipality where the land is located. This means, for example, that farmers would not be able to sell land to outside investors, except (maybe) with government intervention. This clause sets the TSS apart from alternatives currently being pushed by donors: he current trend is towards land titling for local communities and small landholders precisely to allow them sell or lease land to investors. Will the inalienability clause survive this trend if states do adopt the TSS? That is a big question.

The TSS was endorsed by the APF at its 32nd session in July 2013 in Abidjan. The Union is backing a proposal from its African section to establish a commission in charge of drafting a framework law on TSS.16 This commission, once established, will present a draft framework law within 18 months.17 The Parliamentary Assembly of La Francophonie will then design a plan to get this law adopted by two Regional Economic Communities – the Central African Economic Community and the West African Economic and Monetary Union – with the ultimate goal of getting national legislatures in all Francophone countries to do the same. The next step would be to submit the TSS framework law to the African Union for adoption across the continent.

G8 Land Transparency Initiative18

▪ Timeframe: 2013-

▪ Implementing “land partnerships” in 7 African countries: Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, South Sudan and Tanzania.

▪ Global Donor Platform for Rural Development serving as information gateway

The Land Transparency Initiative was launched in June 2013 by the G8 to support greater transparency in land transactions, responsible governance of land tenure and to build capacity on these issues in developing countries. It is being implemented through “partnerships” between G8 members and African countries together with corporations, farmers and civil society. The partnership documents state that they will also implement the FAO’s Voluntary Guidelines at the national level. No details are available on how this is taking place.

Information about, and accountability for, the land partnerships is handled by the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development (Donor Platform), a network of 37 financing institutions, intergovernmental organisations and development agencies created in 2003.19The Donor Platform has three activities on land: managing a database of more than 400 land projects funded by its members, operating a Global Donor Working Group on Land and serving as communication hub for the G8 LTI.20

There is significant overlap between the G8 LTI and the Donor Platform. Six of the eight G8 members are part of the Donor Platform: France (AFD), Italy (Cooperazione Italiana), Canada (Foreign Affairs), Germany (Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development), the UK (DFID) and the US (USAID). The people or agencies representing three of those countries within the Platform are the same ones that lead their countries’ G8 land partnerships. But the Donor Platform is not responsible for the LTI: its secretariat just provides information about it on the G8’s request.

But there is a clear relationship between the G8 land partnerships and the G8 New Alliance framework agreements when it comes to their implementation in African countries that are part of both initiatives. This relationship is most apparent when the G8 country is the same lead country for both programmes. In Ethiopia, for example, the land partnership is framed as a “continuation” of the commitments made under the G8 New Alliance. The partnership may also have links with other activities of the donor state in the African partner. In Burkina Faso, for example, the partnership with the US builds on the MCC’s support to implementation of the country’s Rural Land Act.

No further details could be obtained from the platform secretariat or individuals in charge of coordinating specific partnerships, much less the budget.

The BF partnership aims at supporting the implementation of Burkina’s 2009 Rural Land Law. It builds on the MCC programme in the country and is led by MCA Burkina for the Burkinabé government, and by MCC and USAID for the US government. The Partnership will also promote adherence to principles outlined in the VGs.

Suzanne Ouedraogo, a farmer from Burkina Faso: her government is being urged to transform and absorb customary land and agriculture systems into Western-style markets. Who will benefit? (Photo: Pablo Tosco/Oxfam)

The priorities for 2014 are: completion of the Land Governance Assessment Framework for Burkina Faso, a World Bank project; design and launch of a national land observatory; finalisation of a pilot project to track and enhance transparency of land transactions; provision of resources to ensure that gender equity is incorporated into all efforts; and a multi-stakeholder dialogue. The expected outcomes are: reduced land conflicts, increased recognition of land rights, expanded access to land rights by women, and improved transparency and efficiency in land transactions.Ethiopia-UK, US, Germany

The Ethiopia partnership was agreed to in December 2013. It is supposed to serve as a continuation of the commitments made under the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. No further information is available.

Niger-EU

The land partnership between the EU and the government of Niger will focus on a review of land policy under Niger’s Rural Code and harmonisation with the FAO’s Voluntary Guidelines and the African Framework on Land Policy.

Nigeria-UK

The Nigeria partnership aims to increase, by mid-2015, the transparency and reliability of land titling in Nigeria, and to stimulate investment in agriculture. The UK government is providing an international expert in land titling and land tenure assessments, as well as expertise from FAO. Other resources such as geographic information system equipment and satellite imagery have also been provided to do initial titling work in 2014.

Senegal-France

The Senegal partnership focuses on helping Senegal “get the best out of commercial land deals”. Specifically, in 2014-2015, the initiative will support the National Commission on Land Reform (established in March 2013), the creation of a Land Observatory, training on land conflict prevention and resolution, and public awareness-raising about the Voluntary Guidelines as international standards.

South Sudan-European Union

The South Sudan partnership will establish a land governance system through implementation of the 2013 USAID-assisted Land Policy, which is supposedly in line with the Voluntary Guidelines and the African Framework on Land Policy. The EU will support the drafting and adoption of a Land Act and necessary regulations for its implementation, as well as the creation of a digital land registry within the Ministry of Land. An action plan on administration, regulation and allocation of land for agricultural investment will also be developed.

Tanzania-UK

The land partnership aims to strengthen land governance in Tanzania, stimulate investment in productive sectors and strengthen land rights for all Tanzanians. These objectives are set to be achieved by mid-2015. Besides the UK, the Tanzania partnership involves kthe World Bank, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, the EU, the US, representatives of transnational business (i.e. BP, BG Group), and civil society (i.e. Oxfam, Concern). The partnership will be implemented through a Land Tenure Unit in the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development.

Concrete actions towards implementation of the Tanzania partnership include: piloting of systematic regularisation of land tenure nationwide; design and operationalisation of open data systems for all land investments above 50 hectares; development and funding of 5-year national investment plan in land titling.

US Millennium Challenge Corporation

▪ Proponent: US government

▪ Format: 5-year programmes to fight poverty in countries that qualify for funding

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is a US aid agency that was created by the US Congress in 2004 with a mandate to promote free market reforms in the world’s poorest countries. The MCC’s works towards this goal by providing least developed countries with grants (or at least the prospect of grants) for large projects that they and the MCC identify in exchange for the adoption of free market reforms. The projects are implemented and overseen by agencies known as Millennium Challenge Accounts (MCA).

The MCC first evaluates whether a country is eligible for assistance based on a set of its own criteria. If deemed eligible, the MCC and the government negotiate a generous 5-year programme known as a Compact. If a country is deemed ineligible, the government has to implement a number of reforms identified by the MCC to be considered for funding. Countries that come close to meeting MCC criteria and commit to improving their performance may be awarded smaller grants known as threshold programmes..

Land in both urban and rural areas is a major target of the MCC programmes. To date, it has invested almost US$260 million in property rights and land policy reforms through 13 of its 25 Compacts.23

The Millennium Challenge Corporation’s land policy programmes are often closely connected to major infrastructure development projects – also financed by the MCC – designed to support agricultural commodity markets, such as dams, roads, irrigation and ports.

The MCC’s various land reform efforts in Africa have consistently sought to formalise customary or informal land systems; map out and divide lands with the use of new cadastral and mapping technologies; allocate individual titles to lands; simplify and facilitate land transfers; and promote and facilitate agribusiness investment.

The approach is not to completely sidestep customary forms of land management or local participation. The MCC typically integrates some basic elements of local practices to map out and allocate lands as a means to then establish forms of title that can be transferred (i.e. sold). As MCC puts it, “Formalisation of existing practices and rules is a way to make them more compatible with modern economies and production systems.”24

The MCC’s projects often work at two levels: through specific land allocation and securisation projects that can serve as models, and through land policy processes, where the MCC often plays a direct role in high-level government processes to reform land legislation.

Details of the MCC’s involvement in nine African countries are presented in Annex 3. What they show is a deep and powerful engagement by the US government to transfer and transform customary systems of land management and control (in)to formal markets and private property. Deep, because the MCC’s in-country work has changed not only laws but the institutional fabric to administer new land rights. And powerful because they have been very effective.

In Benin, for example, the MCC’s work to rewrite the country’s land law in favour of strong property titles at the expense of customary rights met resistance from farmers organisations and civil society, but still managed to achieve most of its objectives. In Burkina, its work to transform and absorb customary systems into Western-type markets is making headway and being carried further by the US government within the context of the G8 Land Transparency Initiative. In Ghana and Mozambique, the MCC has been quite effective in getting land titles distributed to replace traditional systems.

Initiatives introducing seed laws

Tending seedlings in Kenya: future prisoners of plant variety protection laws? (Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP)

Tending seedlings in Kenya: future prisoners of plant variety protection laws? (Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP)Under the rubric “seeds laws” there are various types of legal and policy initiatives that directly affect what kind of seeds small scale farmers can use. We focus on two: intellectual property laws, which grant state-sanctioned monopolies to plant breeders (at the expense of farmers’ rights), and seed marketing laws, which regulate trade in seeds (often making it illegal to exchange or market farmers’ seeds).25

Plant Variety Protection

Plant variety protection (PVP) laws are specialised intellectual property rules designed to establish and protect monopoly rights for plant breeders over the plants types (varieties) they have developed. PVP is an offshoot of the patent system. All members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are obliged to adopt some form of PVP law, according to the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). But how they do so is up to national governments.

African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO) draft PVP Protocol

• Draft PVP Protocol to be implemented in the 19 ARIPO member states: Botswana, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Somalia, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

ARIPO is the regional counterpart of the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) for Anglophone Africa. It was established under the Lusaka Agreement signed in 1976. In November 2009, ARIPO’s Council of Ministers approved a proposal for ARIPO to develop a policy and legal framework which would form the basis for the development of the ARIPO Protocol on the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (the PVP Protocol). Adopted in November 2013, the legal framework was formulated into a Draft PVP Protocol in 2014 during a diplomatic conference.26

The Draft PVP Protocol establishes unified procedures and obligations for the protection of plant breeder’s rights in all ARIPO member states. These rights will be granted by a single authority established by ARIPO to administer the whole system on behalf of its member states.

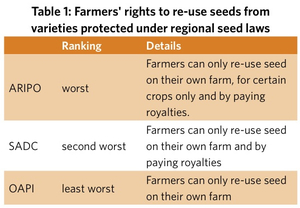

The Protocol is based on the rules contained in the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention. It therefore establishes legal monopolies (“protection”) on new plant varieties for 20-25 years, depending on the crop. Farmers will not be able to save and re-use seed from these varieties on their own farms except for specifically designated crops, within reasonable limits, and upon annual payment of royalties. Under no circumstances will they be able to exchange or sell seeds harvested from such varieties.

In April 2014, the ARIPO Draft PVP Protocol was submitted to UPOV for examination of its conformity to UPOV 1991. The UPOV office concluded that “once the Draft Protocol is adopted with no changes and the Protocol is in force,” ARIPO and its member states will be in a position to join UPOV.27

The Protocol is hotly contested by civil society. 28 AFSA, for instance, is on record for vehemently opposing the ARIPO PV Protocol on the grounds that it, inter alia, severely erodes farmers’ rights and the right to food. On the other hand, industry associations have been consulted extensively in the process of drafting the ARIPO PVP Protocol. The International Community of Breeders of Asexually Reproduced Ornamental and Fruit Varieties (CIOPORA), African Seed Trade Association (AFSTA), the French National Seed and Seedling Association (GNIS) and foreign entities such as the United States Patent and Trademark Office, the UPOV Secretariat, the European Community Plant Variety Office have all had input.

At a regional workshop on the ARIPO PVP Protocol in Harare, Zimbabwe, at the end of October 2014, member states unanimously endorsed the need for further consultations to be held at national levels and for an independent expert review of the draft ARIPO PVP Protocol to be conducted prior to any adoption of the instrument.

Organisation Africaine pour la Propriété Intellectuelle (OAPI) revised Bangui Agreement

• The revised Bangui Agreement (Annex X) has been in force in OAPI member states since 2006: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal and Togo.

OAPI is the regional intellectual property organisation for 17 mainly Francophone African countries. It was established in 1977 by the Bangui Agreement, and revised in 1999 to align it with the WTO TRIPS Agreement. The revised Bangui Agreement entered into force in 2006. It made OAPI the first African organisation to establish a PVP system based on UPOV 1991.

Annex X of the Revised Bangui Agreement focuses on plant variety protection. Similar to the ARIPO Draft PVP Protocol, it confers on breeders an exclusive right to “exploit” new plant varieties for 25 years. Farmers are nonetheless allowed to save and re-use seed from protected varieties on their own farms − for any crops and without paying successive royalties. But like all UPOV-modelled laws, the Bangui Agreement makes it illegal for farmers to share, exchange and selling farm-saved seeds of protected varieties outside their own farms.

In June 2014, OAPI became a member of UPOV.29 This means that in the future it is likely that the rights of breeders in the OAPI member states will get stronger and those of farmers will get weaker, because the purpose of UPOV is to protect breeders against competition from farmers.

It should also be noted that there is currently a proposal to merge OAPI and ARIPO to form a single Pan African Intellectual Property Organisation (PAIPO).30 This would take place in the larger context of the creation of a continental Free Trade Agreement in Africa.31

Southern African Development Community (SADC) draft PVP Protocol

• Draft PVP Protocol to be implemented in SADC member states: Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

The SADC draft PVP protocol, like the equivalent legal instruments of ARIPO and OAPI, intends to establish a protection system modelled after UPOV 1991 in the SADC region. The main features of this protocol are the same as those of the ARIPO and OAPI, with the exception of the farm-saved seeds provision. Farmers in the SADC region will be able to save and re-use seeds only on their own farms, and only by paying royalties. Table 1 compares the three regional laws.

All SADC countries, except Angola, are members of ARIPO. This means that the PVP protocols of both organisations will apply in eight countries. It is not clear whether seed companies will be able to get double protection on their varieties under the two instruments simultaneously or have to choose one or the other. The economic implications for farmers in terms of their right to save and re-use seeds depending on either outcome will be quite serious.

The chief concern for AFSA members is that UPOV 1991, on which the SADC protocol is based, is a restrictive and inflexible legal regime that grants extremely strong intellectual property rights to commercial breeders and undermines farmers’ rights. Such a regional law will most certainly increase seed imports, reduce breeding activity at the national levels, facilitate monopolisation of local seed systems by foreign companies, and disrupt traditional farming systems upon which millions of African farmers and their families depend for their survival.

AFSA has also raised serious concerns about the lack of consultation with smallholders and civil society regarding the modelling of the draft SADC PVP Protocol on UPOV 1991. It is true that SADC has agreed to incorporate provisions on “disclosure of origin” and “farmers’ rights” which now render the protocol technically non-compliant with UPOV. However, SADC members who are also member states of the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO) will now opt to ratify the ARIPO PVP Protocol. It is revealing that money is now being poured into the ARIPO process, while there are scant resources available to push forward with the adoption of SADC’s protocol.

US and European free trade agreements

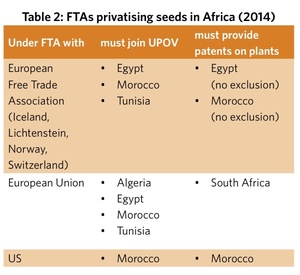

Since the late 1990s, the US and Europe have been pushing bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) into Africa as tools to gain market advantages for their transnational corporations. This affects seeds. Bilateral FTAs tend to set standards that go beyond the global standards set, for example, at the World Trade Organization. The WTO TRIPS Agreement, which most African countries are party to, says that members do not have to grant patents on plants and animals. But it does require that members implement some kind of intellectual property protection on plant varieties without stipulating what form this should take.

Not content with the terms of the TRIPS Agreement, the US and Europe have been going further and signing bilateral trade deals with African states that specifically require the signatory governments to implement the provisions of UPOV or, worse, to become member of the Union. Some FTAs even require full-fledged industrial patenting of seeds. The table below summarises the current situation.

Presently, the EU is also negotiating comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with most of sub-Saharan Africa as well as Deep and Comprehensive FTAs with the southern Mediterranean countries that are expected to further expand intellectual property rights for corporations over seeds. That means that they will impose UPOV and/or patenting. This is to ensure that companies get a return on their investment by obliging farmers to pay for seeds – including farm-saved seeds.

Seed marketing rules

The second category of seed laws consists of rules governing seeds marketing in and among countries. A number of current initiatives aim to harmonise these rules among African states belonging to the same Regional Economic Community. But through harmonisation, states are actually being encouraged to “liberalise” the seed market. This means limiting the role of the public sector in seed production and marketing, and creating new space and new rights for the private sector instead. In this process, farmers lose their freedom to exchange and/or sell their own seeds. This legal shift is deliberately meant to lead to the displacement and loss of peasant seeds, because they are considered inferior and unproductive compared to corporate seeds.

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA)

The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) was established in 2006 by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. It is currently funded by several development ministries, foundations and programmes, including DFID, IFAD and the Government of Kenya. AGRA’s objective is to “catalyse a uniquely African Green Revolution based on smallholder farmers so that Africa would be food self-sufficient and food secure.”32AGRA focuses on five areas: seeds, soil health, market access, policy and advocacy and support to farmers’ organisations.

On seeds, AGRA’s activities are implemented through the Programme for Africa’s Seed Systems (PASS). PASS focuses on the breeding, production and distribution of so-called “improved” seeds. AGRA’s action on seeds policies and laws, however, is carried out through its Policy Programme, whose goal is to establish an “enabling environment”, including seed and land policy reforms, to boost private investment in agriculture and encourage farmers to change practices. This specifically includes getting the public sector out of seed production and distribution.

AGRA’s seed policy work aims to strengthen internal seed laws and regulations, reduce delays in the release of new varieties, facilitate easy access to public germplasm, support the implementation of regionally harmonised seed laws and regulations, eliminate trade restrictions and establish an African Seed Investment Fund to support seed businesses.

In Ghana, for example, AGRA helped the government review its seed policies with the goal of identifying barriers to the private sector getting more involved. With technical and financial support from AGRA, the country’s seed legislation was revised and a new pro-business seed law was passed in mid-2010.33 Among other things it established a register of varieties that can be marketed. In Tanzania, discussions between AGRA and government representatives facilitated a major policy change to privatise seed production. In Malawi, AGRA supported the government in revising its maize pricing and trade policies.34

AGRA is also funding a $300,000 seeds project for the East African Community that started in July 2014 and will be implemented over the next two years. Its objective is to get EAC farmers to switch to so-called improved seeds and to harmonise the seed and fertilizer policies of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda.

With this AGRA project, the EAC joins the other African Regional Economic Communities that have jumped on the bandwagon to harmonise seed trade rules in Africa. This is part of a coordinated action by all these key players − the World Bank, the G8, AGRA, the seed industry, and development cooperation ministries − to use RECs as means of realising their objective of changing African seed laws to set up a profitable market for private corporations involved in seed production and distribution, and to dismantle the role of the State in both the seed and fertiliser sectors (see below).

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) seed trade harmonisation regulations

• Since 2013

• 20 COMESA member States: Burundi, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sudan, South Sudan, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The COMESA seed trade regulations were drawn up with the help of the African Seed Trade Association and approved in September 2013 by the COMESA Council of Ministers.35 Their main objective is to facilitate seed trade among the 20 member states of COMESA by pushing these states to adopt the same standards for seed certification and phytosanitary rules, and by establishing a regional variety catalogue containing the list of authorised seeds to be marketed and grown in the region. The standards promote only one type of plant breeding, namely industrial seeds involving the use of advanced breeding technologies.

Like in other regional seed harmonisation initiatives, the COMESA seed regulations make transboundary movement of non-registered seeds illegal. Only approved varieties (that are distinct, uniform and stable, the same criteria used for PVP) can move from one country to another. Farmers’ seeds, local varieties and traditional materials will fall outside this net and be marginalised. The regulations will therefore have the effect of entrenching existing bans in many countries on the marketing of both farmer and unregistered varieties within national boundaries.

The COMESA seed trade regulations will be implemented by eight member states which are simultaneously members of SADC, which has also adopted a set of Technical Agreements on Harmonisation of Seed Regulations. This set of Agreements differs from the COMESA regulations in aspects relating to the registration of traditional varieties and the registration of genetically modified (GM) varieties. The incompatibility between these regulations may raise practical difficulties “and will no doubt give rise to a great deal of anomalies and confusion”.36

The COMESA seed regulations are binding on all COMESA Member States in terms of article 9 of the COMESA Treaty. Yet there is no evidence to demonstrate the involvement of and consultation with the citizens in COMESA countries, particularly small-scale farmers, despite numerous pleas to COMESA to consult with small farmers.

ECOWAS seeds regulation

• Since 2008

• Applies to ECOWAS countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

The ECOWAS seeds regulation was adopted in May 2008 in Abuja, Nigeria.37 It harmonises the rules governing quality control, certification and commercialisation of seeds and seedlings in ECOWAS member states. The main objective is to facilitate seed trade among member states. To achieve harmonisation, the regulation sets out principles and leaves it up to the states to adopt their own standards on the basis of internationally accepted ones.38

For the purpose of organising the common market between ECOWAS member states, seeds are allowed to move freely in the ECOWAS zone once they meet the standards applicable in that zone. These standards require that member states certify seeds on the basis of ECOWAS specifications and anchor their technical regulations on international standards. Therefore, seeds released in one country can be freely marketed in any other country of the common market (except for GM seeds which can only be released nationally until there is a regional biosafety framework in place).

The ECOWAS regulation also set up a West African Catalogue of Plant Species and Varieties. Each member state is also obliged to establish a national catalogue and a national seed committee. The regional catalogue contains the list of all varieties registered in the national catalogues of member states. Only seeds registered in these catalogues are authorised to be commercialised in the territory of ECOWAS.

As of 2013, only eight countries had initiated the process of reviewing their national seed regulatory framework to conform with the ECOWAS common rules: Benin, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire and Gambia. For this reason, a separate project was created to boost its implementation and improve the level of use of certified seeds within the region. That project, supported by USAID, is described below.

Southern African Development Communities (SADC) technical agreements on harmonisation of seed regulations39

• In force in SADC members states since 2008: Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Adopted in 2008, the SADC Technical Agreements on Harmonisation of Seed Regulations focus on variety release, seed certification and phytosanitary measures for the movement of seeds. The objective of the agreements is to facilitate seed trade in the SADC states and increase the availability of so-called improved seeds from the private sector.

Through the variety release system, a SADC seed catalogue has been established, just like in the ECOWAS and COMESA regions. Seed of varieties listed in the catalogue can be traded in all SADC member states with no restrictions. A variety cannot be listed in the regional catalogue until it is released nationally in at least two SADC countries. And it must meet the test of distinctness, uniformity and stability (as for PVP), plus value for cultivation and use.

For farmers who are used to working with traditional seeds of local varieties, this represents a very complex system. Given that the harmonisation aims at generalising the use of industrial and uniform seeds, the informal seed system of farmers will be in jeopardy. SADC does aim to document traditional varieties in its seed database but the Agreements are silent on who is entitled to register these materials and the objective of such registration.

It is noteworthy that the SADC harmonisation agreements do not allow for the release of GM seeds. These varieties will be authorised once a common position is reached among the SADC members on biosafety and the use of GMOs. 40

USAID West African Seed Project (WASP)41

▪ Proponent: US Agency for International Development

▪ Timeframe: 2012-2017

▪ Budget: US$8million

▪ 7 ECOWAS countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal

The West Africa Seed Program is a five-year initiative funded by USAID and implemented through the West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development. Its purpose is to help countries implement the ECOWAS seed regulations. It specifically targets increasing the use of certified seeds (in place of traditional farm-saved seeds) from its current level of 12% to 25% by 2017.42 It focuses on seven ECOWAS countries (Benin, Burkina Faso Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal) while its policy activities cover all ECOWAS states plus two CILSS countries, Chad and Mauritania.

WASP first aims to restructure the West African seed sector. It will create an Alliance for Seed Industry in West Africa (ASIWA) and a West Africa Seed Committee (WASC/COASem). These two bodies are be established in 2014.43 ASIWA will promote industrial seed distribution and marketing in the region. As for the WASC, it will oversee the implementation of the seed regulation through the ECOWAS zone, as described in the section above.

WASP’s second objective is to improve implementation of the ECOWAS seed regulation to boost trade in commercial seeds in West Africa and enhance the participation of the private sector in the seed industry. WASP specifically aims to help revise national laws and align them on the basis of C/Reg.4/05/2008 and create a seed committee which will develop a seed catalog for all seven countries of implementation. Once seeds are listed in this catalog, any country can produce and sell them.

A third target is to enhance private sector engagement in the seed sector in West Africa. WASP intends to strengthen the capacities of National Seed Trade Associations through training. Seed production plots will be established by the private sector groups involved in the programme, and demonstration plots will be created to showcase new varieties and organise field days for farmers to learn new techniques. The WASP and its private partners will also train small-scale farmers to produce new seeds. These farmers will participate in continued trainings to learn new techniques, experiment with producing hybrid seeds, and contribute their ideas to a wider network of producers. The WASP’s plan is to make these farmers “individuals whom other farmers seek out for advice about new seed varieties, access to those seeds, and cultivation.” 44

This approach is highly similar to AGRA’s actions in the seed sector in Africa. The WASP mentions AGRA amongst organisations with which it is partnering in the implementation of its action plans. No further details are provided on the “how” of this partnership. It will not be surprising to see AGRA play a role in WASP’s implementation, specifically in building ASIWA and getting the private sector involved in seed production and distribution.

This is all the more important given that AGRA is already implementing projects in some WASP countries. In Mali, for example, AGRA is trying to get farmers to use so-called improved seeds and fertilisers to improve productivity.45

Annex 1: G8 New Alliance plans and impacts so far

The government has agreed to extend the rural land ownership plan (Plan Foncier Rural or PFR), already in force within its legislation, to cover the entire country by December 2018. The PFR is an instrument introduced in some West African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire) in the late 1980s to formalise land tenure. It introduces surveying and mapping of agricultural fields, identification and registration of customary rights of possession (formal list of landholders), and the creation and archiving of written documents of land transactions (land sale contracts and agreements of tenancy and subordinate use) in every single village.47 As of September 2014, 386 villages in 45 communes had been covered.

Under the New Alliance, Benin has made no commitment to change its seed laws.

On seeds, the government of Burkina Faso pledged to revamp the national seed legislation to clearly define the role of the private sector in the breeding, production and marketing of certified seeds by December 2014. According to a May 2013 progress report, Burkina Faso’s Seed Act and regulations were being revised to conform with regional standards, i.e. the laws and regulations adopted by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU).

The ECOWAS seed regulation sets out rules for seed certification and registration, modelled on European law. Any seed that is not listed in the official catalogue of registered varieties cannot be traded across borders in the ECOWAS states. Burkina will now have to establish the same system at the national level. Burkina is also member of the African Intellectual Property Organisation (OAPI) and therefore subject to OAPI’s new plant variety protection (PVP) system as entrenched in the revised Bangui Agreement. This new law is modelled on the convention of the Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plant (UPOV), a kind of patent system for plants which also originates in Europe.49

On land, several measures to formalise tenure and document rights are under way:

▪ The government agreed to take actions to clarify the conditions for developing, occupying and using State or local government-developed lands. Three decrees were passed in September 2012 to regulate the occupation and use of land for rain fed agriculture, family plots and commercial agriculture.

▪ The government also committed to adopt, by December 2013, a policy framework for the resettlement of farmers affected by development projects. The Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), the implementing agency for the MCC programme in Burkina, suggested using the World Bank’s Involuntary Resettlement Policy50 as a basis. According to the New Alliance’s May 2013 progress report, this was accepted and would be applied in the Bagré Growth Pole, a project supported by the World Bank.

▪ Another commitment concerns stepping up implementation of law N° 034-2009 and its decrees on rural land tenure and the delivery of land certificates at village level. Three measures are being taken: a national committee on rural land tenure is up and running along with 13 regional committees; rural land agencies are being set up in the country’s 302 rural districts (pilot operations in 66 municipalities); and village land commissions (1171 so far) and village land conciliation commissions (419 to date) are being established nationwide. These commissions are being established in the areas where MCA Burkina operates.

▪ Finally, the G8 agreement obliges the government of Burkina Faso to draft procedures for access to state land by December 2014; demarcate and register developed land areas; and issue land-use rights documents in all developed areas. The progress report states that this process is ongoing in the World Bank-funded Bagré Growth Pole where, as of July 2014, the government had allocated 13,023 hectares of land to 108 investors (5% of them foreigners).

The government of Côte d’Ivoire committed, under the G8 New Alliance, to accelerate the demarcation of village lands and the issuing of land certificates by June 2015 under its Rural Land Act. It also agreed to extend and operationalise its land information system across the entire country and adopt specific measures to increase access to land in rural areas for women and young people. Another commitment was to adopt a law on transhumance by December 2013, which as of July 2014 had been drafted but not adopted.

In January 2013 the government announced that as part of its partnership with the G8, it was giving the French agribusiness titan Louis Dreyfus Commodities (LDC) 100,000 to 200,000 hectares in the north of the country to grow rice. The government stressed that this land would not be taken from farmers, as Ivorian law does not allow foreigners to own farmland (only rent it from the state). Instead, the farmers would work as contract labourers for LDC. By June 2014, LDC said it was abandoning the project, as the government was not following through on its pledge.52

Abidjan also agreed to adopt a new seed law in line with the regional legislation drawn up through WAEMU and ECOWAS, and simplify procedures for the approval and registration of plant varieties in the official catalogue.

For the G8 New Alliance, the Ethiopian government committed to approving a new seed law to increase private sector participation in seed development, multiplication and distributionA new seed proclamation was duly adopted in January 2013, and the Ministry of Agriculture has drafted the implementing regulations.54 It sets rules for the certification and marketing of seeds, but does not apply to farm-saved or farmer-exchanged seeds. It is worth nothing that both the G8 and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation supported this process.

On land tenure, the government of Ethiopia committed to extending land certification to all rural landholders, initially focusing on zones hosting Agricultural Growth Programmes. According to the New Alliance progress report of May 2013, almost 90% of households in these zones were registered and more than 70% of them received first-level landholding certificates.55 According to the 2014 progress report, the government had issued certificates to 98% of rural households in the four main regions that have local land proclamations (Amhara, Oromiya, SNNPR and Tigray). In 2014, a start was made to issue second-level land certificates in eight woredas in each of the same regions.

The government pledged to take several other measures to strengthen land rights for investors. Addis agreed to revise the land law by December 2013 to encourage long-term leasing and to strengthen contract enforcement for commercial farms. The federal proclamation on land administration (456/2005), adopted in 2005, sets the rules for land ownership and leasing in Ethiopia.56 This law had already been used in the four aforementioned regions to develop regional proclamations. According to the New Alliance , three other regions (Afar, Gambella and Somali) also issued regional land laws based on the new statute.

Ethiopia also agreed to develop and implement guidelines for corporate responsibility for land tenure and responsible agricultural investment. The 2014 progress report states that the government envisages adopting the FAO Voluntary Guidelines on land tenure for this purpose. The EU, through the German agencies BMZ and GIZ, is exploring the potential to assist the Ethiopian Land Investment Agency with this.

In its G8 New Alliance framework agreement, Ghana committed to adopting policy that would encourage the private sector to develop and commercialise so-called improved seeds. To achieve this, the government agreed to draw up regulations to implement new seed legislation adopted in 2010. This would provide for the establishment of a seed registry system; the development of protocols for variety testing, release and registration; authorisation to conduct field inspections, seed sampling and seed testing; and the setting of standards for seed classification and certification.

Another policy action pledged by the government was the adoption of a new agricultural input policy that would specifically define the role of government in seed marketing, and that of the private sector in plant breeding. It should be noted that in the World Bank’s Agricultural Development Policy Operations (AgDPO) of Ghana, it clearly states that the government will pull out of the production and distribution of seeds.

On land, the government agreed to support the private sector by establishing a database of lands suitable for investors. The database was to register 1,000 hectares by December 2013, 4,500 hectares by December 2014, and 10,000 by December 2015. Pilot model lease agreements will be developed for 5,000 ha land deals by December 2015. These agreements will focus mainly on outgrower schemes and contract farming.

For traditionally-held lands included in the database, the government will conduct “due diligence” and “sensitisation” activities in nearby communities in order to clarify the rights and obligations of customary rights holders under the lease agreements they will be “entitled” to sign with investors.

It’s important to note that the government’s land commitments towards investors are also included in the Ghana Commercial Agriculture Project (GCAP), a project funded by the World Bank and USAID independently of the G8 New Alliance. The Ghana AgDPO, financed by World Bank, also specifies that access to land will be provided to private investors through GCAP.

With the G8 New Alliance, the government of Malawi has committed to giving private investors improved access to land, water, farm inputs and basic infrastructure. To achieve this, it will adopt a new land bill and conduct a survey to identify unoccupied land under both customary ownership and leasehold, as well as determine crop suitability, with the view to setting aside 200,000 hectares for large scale commercial agriculture by 2018. The 2014 Progress Report on Malawi confirms that a new land bill was passed by parliament.59However, it was then subjected to comments by civil society and the president returned it to parliament for review instead of endorsing it. The report says that some pilot investment schemes have been set up and that the private sector is advocating for scaling these up as a basis for the overall 200,000 ha.

On seeds, Malawi pledged to implement the Southern African Development Communities (SADC) and Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Seed Harmonisation Regulations by 2015. This would require enactment of a plant variety protection law (Malawi’s Plant Breeders’ Right Bill has been concluded and is awaiting enactment), amendment of the phytosanitary legislation (Malawi Plant Protection Act, 1969), review of the national seed certification system (Seed Act, 1996) and review of the current Pesticide Act.

According to the New Alliance’s 2014 progress report, the PBR bill will be tabled at the next session of parliament. The amended Plant Protection Act was submitted to cabinet for endorsement before being passed by parliament. With regards to seed certification, a new Seed Act, drafted with inputs from the private sector, is expected by end of 2014 or early 2015. The Pesticide Act that was scheduled for review by June 2014 underwent revision and the draft bill is with the Ministry of Justice.

Under the New Alliance, the government of Mozambique committed to adopting policies and regulations that promote the role of the private sector in agricultural input markets. In addition to the revision of its seed policy, the government pledged to “systematically cease distribution of free and unimproved seeds, except for pre-identified staple crops, in emergency situations”. Another commitment was to implement approved regulations on PVP law by June 2013, and to align the country’s national legislation on seed production, trade, quality control and seed certification with SADC regulations by November 2013.

The New Alliance’s progress report published June 2014 states that the government has passed Decree 12/2013 which establishes the regulatory framework for production, trade, quality control and seed certification in line with SADC. The process of developing a plant variety protection law and corresponding regulatory framework is also underway. It is expected that this will create conditions for international seed companies to participate in the national seed market. However, an analysis conducted by USAID suggests that the draft PVP regulation will not be effective in the short and medium term due to the fact that 90% of Mozambican farmers are small subsistence producers and 91% of the seed production and trade in the country takes place in the informal sector.61

In terms of land, the government of Mozambique agreed to reform the land use rights system and accelerate issuance of land use certificates (DUATs) to promote “security” for small landholders and agribusiness investment. Specific actions would include reducing processing time and cost to get rural land use rights (by March 2013), and passing regulations and procedures that allow communities to engage in partnerships through leases or sub-leases (by June 2013). According to the first progress report (May 2013), procedures for areas under 10 hectares had been drafted and are being piloted in targeted communities. The Ministry of Agriculture also produced and published a statement (in August 2012) on simplification in the transfer of DUATs in rural areas.

Regarding allowing communities to lease and sublease their lands, the 2014 progress report states that regulations have been drafted and are being examined by stakeholders before proceeding to legislation. However, due to the October 2014 elections in October 2014, the legislation was not expected to be presented to the cabinet before the end of 2014.

Nigeria pledged to pass and implement a new seed law that supports the role of the private sector in seed development, multiplication and sale, and assigns the public sector a merely regulatory role in conformity with the ECOWAS seed law. This was accomplished with the amendment of the National Agricultural Seeds Act in 2011, and the adoption of a seed policy in 2012. An implementation plan was also adopted in 2013 though it remains to be carried out.

The government also agreed to new measures regarding land tenure. It committed to adopt, between December 2013 and June 2014, a Systematic Land Titling and Registration (SLTR) regulatory framework that “respects” the CFS Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGs). No further detail is given on how the SLTR will do this, but it can be interpreted to mean that the key principles of the VGs will be written into the SLTR regulatory framework. The SLTR will be extended to all Nigerian states by 2016.

It is worth mentioning that under the G8 New Alliance the government also committed to set up and operate Staple Crop Processing Zones (SPCZs). The SCPZs are zones of intensive cultivation of agricultural produce, where agribusiness companies would be incentivised to set up processing facilities. A total of 14 SCPZs will be set up across Nigeria for rice, sorghum and other grains, cassava, fisheries, horticulture and livestock. The Government planned to develop a Master Plan to stimulate private sector investment in the SCPZs by April 2014. In February 2014, the first SCPZ was launched in Kogi State but no information is yet available on how land will be made available to investors in the zones.

Under the New Alliance, the government of Senegal committed to facilitate access to land for private investors and to implement the country’s seed legislation in favour of private companies. As part of the plan, the government will define and implement land reform measures to increase private sector investment, and these measures will likely amount to redefining rights to land in Senegal.

Tanzania committed to adjust its seed policies to encourage greater corporate participation in the domestic and regional seed markets. Significantly, its seed act was revised in November 2012 to align the country’s plant breeder’s rights legislation with the 1991 Act of the Convention for the Protection of New Plant Varieties (UPOV). The government also worked with Zanzibar to pass similar legislation in order to join UPOV. The UPOV Secretariat has recommended to Council that Tanzania be admitted.65

According to AFSA, Tanzania’s new PVP Act will likely increase seed imports, reduce breeding activity at the national level, facilitate monopolisation of local seed systems by foreign companies, and disrupt traditional farming systems upon which millions of smallholder farmers and their families depend for their survival. The entire process of drawing up these laws has been non-participatory, shutting out the very farmers that the laws will purportedly benefit. Neither farmers’ organisations nor relevant civil society organisations have been consulted on these laws.66

Under the rules of the World Trade Organisation Least Developed Countriess are exempt from putting any PVP Law in place until July 2021. Should Tanzania ratify the UPOV 1991 Convention it will be the only LDC in the world to be bound by UPOV 1991.

On land, Tanzania pledged to improve land rights − granted or customary, for both small holders and investors − by means of certificates. To that end, all village lands in Kilombero were to be demarcated by August 2012, and all land in the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) demarcated by June 2014.

The Tanzanian government also plans a land bank, through which land is granted to the Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC) which then leases it through “derivative rights” to investors for a specific amount of time not exceeding 99 years.67 This is important because foreigners cannot be granted land in Tanzania – the assigning of derivative rights through the TIC is now the only means by which investors can gain access to land.68

The TIC serves as the government agent in managing land allocated to investors. The Ministry of Lands remains the sole body with the ability to issue title to land. It is now developing guidelines for accessing land, and working with development agencies to clarify and implement its “land for equity” policy which would allow investors to access land by granting shares to the government (for state lands) or communities when the land belongs to them.69

Annex 2: World Bank country programmes and impacts

The Ghana AgDPO was designed as a three-year programme (three grants of US$ 25 million each) to support the country’s Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy beginning in 2008. The development objectives of the grants were to increase agriculture’s contribution to growth and poverty reduction while improving the management of soil and water resources.

The “prior action”, or condition, for AgDPO3 (2011) was that Ghana pass a new seed law to allow for the implementation of the 2008 ECOWAS regional seed harmonisation regulation. A new national plants bill had already been passed by parliament under AgDPO1 in June 2010 (Ghana Plants and Fertiliser Act). It accommodates the 2008 ECOWAS seed harmonisation regulation, the WTO Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary Agreement, and the International Plant Protection Convention, and thus creates opportunities for the introduction of new seed technology. The World Bank concluded that “implementation of the new legislation is expected to make it attractive for international seed companies to invest in Ghana.”

Actions to take before AgDPO 4 (triggers) were as follows: the establishment and operationalisation of the institutional framework for the implementation of seed law (National Seed Council, Plant Protection Advisory, Council and National Fertiliser Council) and the design of a programme that promotes fertiliser use in conjunction with certified seed and extension.

These two triggers were also met. The three Advisory Councils were established in 2011, and funded through the 2012 budget, to oversee the development of a new technical regulatory framework. They play key roles in the development and implementation of regulations, the facilitation of a new inputs policy, the organisation of council and committee meetings, and the completion of a new seed laboratory. The government also transformed its existing fertiliser subsidy program into a comprehensive agricultural input support programme and opened it to the seed industry and service providers. This will eventually result in the provision of seed technology with fertiliser and agrochemicals as a package to farmers, via a private sector network of some 2,900 agro-input dealers trained by AGRA and IFDC.

Under AgDPO4 (2012), the government was expected to launch local land bank initiatives for the identification of land for outgrower investments with the goal of integrating small farmers into commercial value chains. As this action and the subsequent contract farming and out-grower arrangements overlap with GCAP land activities, the design of land bank activities and the outgrower investment framework are to be accomplished with technical assistance under GCAP and the World Bank-supported Land Administration Project.

Another action to be implemented ahead AgDPO5 focused on the adoption of an Agricultural Input Policy, which would be reflected in subsequent input support programmes. The input policy aims at clarifying the role of the private sector in technology development, seed multiplication, distribution, and knowledge transfer, and clarifying the role of the government regarding the regulatory environment, promotional programmes such as the fertiliser and seed subsidy program.