A Global Perspective on American Child Deaths

You come from a culture where it is okay to kill children,’ the Iraqi woman said. We were sheltering against the wall of a building in Fallujah in April 2004 while the city was under attack by US forces.

I began to protest, but she continued, in broken English: ‘Let me say it another way. You come from a culture where your people think it is okay to kill our children.’

What could I say? There were several little bodies at my feet, bloodied remains laid out on the footpath and covered with thin sheets. The children had been shot by US snipers that day, among at least 1000 civilians killed in that ferocious attack.

This Iraqi woman knew there would be no collective outrage at the killing of Fallujah’s children. No front-page headlines. We would not know their names, see their faces or hear their stories. Their killers would not be pursued, labelled ‘mad’ or ‘evil’, or made to face a court. There would be no calls for ‘change.’

Some commentators have compared the response to deaths of the children in the small American community of Newtown with the young victims of US wars. The point is valid. A life is a life, and all life is precious; a fact that has enough weight of its own without the need to draw comparisons.

Yet the dark, shocking words of the Iraqi woman in Fallujah have been haunting me these past days as the grief of the Newtown shootings has overwhelmed us all.

What might be helpful at this time is to build on this grief and passion of the US and international community, and allow it to shape a wider discussion; to trigger a new empathy for grieving parents everywhere, an empathy that crosses borders, and which might result in change for children worldwide who are affected by US policy.

Whenever I’ve been with parents grieving their children lost in the violence of recent wars, the same questions has emerged out of their grief and anger: ‘How would the US President feel if his children were killed in a bombing? How would Americans feel? How would your people feel?’

The question grasps at the hope that if those in the West made the effort to imagine how they might feel to lose a child violently to a drone strike, a missile, or a sniper, the result would be greater empathy and understanding.

The endless, heartbreaking cries at yesterday’s prayer vigil for the Newtown victims provided a glimpse of the horror, the emptiness, the confusion that grieving parents feel. The profound love parents have for children is something all cultures have in common.

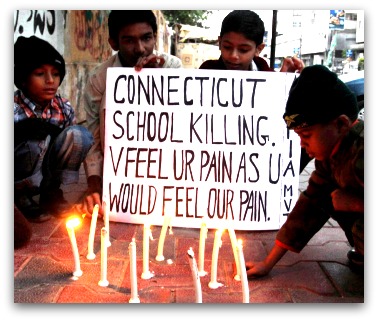

In an amazing scene, Pakistani children held a candlelight vigil in Karachi, in solidarity with children from Sandy Hook Elementary School. They held a sign that read: ‘Connecticut School Killing: We feel your pain as you would feel our pain.’ The children were referring to the (according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism) 176 children who’ve been killed by US drone strikes in Pakistan since 2004; ‘collateral damage’ in the ‘war on terror’.

Americans are now accusing the powerful Nation Rifle Association of treating victims of US gun massacres as ‘collateral damage’ of the right to bear arms — the ‘price’ that has to be paid for freedom.

The deaths of the Newtown children and of Pakistani children may both be the result of self-interested US political policy and an all-pervasive culture of violence. But there’s one major difference that grieving parents in Pakistan, Iraq, Afghanistan and Gaza would point out.

The Newtown killings are considered an act of someone who is ‘sick’ or ‘mad’, and are universally condemned. But their children are killed at the hands of an intelligent, sophisticated, technologically advanced society which is fully aware of what it is doing. These deaths receive little attention, let alone condemnation.

This reality created an awkward elephant in the room during Barack Obama’s passionate call for change at yesterday’s prayer vigil. ‘This is our first task, caring for our children,’ he said. ‘If we don’t get that right, we don’t get anything right. That’s how, as a society, we will be judged.’

He talked about victims who ‘much of the time their only fault was being at the wrong place at the wrong time. We can’t tolerate this anymore. These tragedies must end. And to end them, we must change. Are we prepared to say that such violence visited on our children year after year after year is somehow the price of our freedom?’

When I imagined Obama’s words ‘our children’ as referring to all the children of the world who are impacted by US war policy, I shivered with hope.

Perhaps the grieving parents of Newtown, who share the loss of parents in Pakistan and Afghanistan, can lead him to this bigger, more compassionate version of ‘our children’.

When I speak to ordinary people around Australia about children as the victims of war, there is outrage. People care, they want to know their names, see their faces, hear their stories.

For this natural empathy to be activated we need the mainstream media to broaden their scope, and western leaders such as Obama to broaden their circle of care.

Donna Mulhearn is a freelance journalist and peace activist. She will return for her fifth visit to Iraq early next year. Follow Donna on Twitter