10 Years Later: The Mysterious Why of the Iraq War

Americans today know a lot more about Iraq than they did ten years ago, knowledge gained painfully from the blood of soldiers and civilians. But a crucial question remains: why did George W. Bush and his neocon advisers rush headlong into this disastrous war, a mystery Robert Parry unwinds.

A decade after President George W. Bush ordered the unprovoked invasion of Iraq, one of the enduring mysteries has been why. There was the rationale sold to a frightened American people in 2002-2003 – that Saddam Hussein was plotting to attack them with WMDs – but no one in power really believed that.

There have been other more plausible explanations: George Bush the Younger wanted to avenge a perceived slight to George Bush the Elder, while also outdoing his father as a “war president”; Vice President Dick Cheney had his eye on Iraq’s oil wealth; and the Republican Party saw an opportunity to create its “permanent majority” behind a glorious victory in the Middle East.

Image: A satirical Mad magazine poster connecting George H.W. Bush’s Persian Gulf War against Iraq in 1991 with George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Though George W. Bush’s defenders vigorously denied being motivated by such crass thinking, those rationales do seem closer to the truth. However, there was another driving force behind the desire to conquer Iraq: the neoconservative belief that the conquest would be a first step toward installing compliant pro-U.S. regimes throughout the Middle East and letting Israel dictate final peace terms to its neighbors.

That rationale has often been dressed up as “democratizing” the Middle East, but the idea was more a form of “neocolonialism,” in which American proconsuls would make sure that a favored leader, like the Iraqi National Congress’ Ahmed Chalabi, would control each country and align the nations’ positions with the interests of the United States and Israel.

Some analysts have traced this idea back to the neocon Project for the New American Century in the late 1990s, which advocated for “regime change” in Iraq. But the idea’s origins go back to the early 1990s and to two seminal events.

The first game-changing moment came in 1990-91 when President George H.W. Bush showed off the unprecedented advancements in U.S. military technology. Almost from the moment that Iraq’s Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, the Iraqi dictator began signaling his willingness to withdraw after having taught the arrogant al-Sabah ruling family in Kuwait a lesson in power politics.

But the Bush-41 administration wasn’t willing to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the Kuwait invasion. Instead of letting Hussein arrange an orderly withdrawal, Bush-41 began baiting him with insults and blocking any face-saving way for a retreat.

Peace feelers from Hussein and later from Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev were rebuffed as Bush-41 waited his chance to demonstrate the stunning military realities of his New World Order. Even the U.S. field commander, Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, favored Gorbachev’s plan for letting Iraqi forces pull back, but Bush-41 was determined to have a ground war.

So, Gorbachev’s plan was bypassed and the ground war commenced with the slaughter of Iraqi troops, many of them draftees who were mowed down and incinerated as they fled back toward Iraq. After 100 hours, Bush-41 ordered a halt to the massacre. He then revealed a key part of his motivation by declaring: “We’ve kicked the Vietnam Syndrome once and for all.” [For details, see Robert Parry’s Secrecy & Privilege.]

Neocons Celebrate

Official Washington took note of the new realities and the renewed public enthusiasm for war. In a post-war edition, Newsweek devoted a full page to up-and-down arrows in its “Conventional Wisdom Watch.” Bush got a big up arrow with the snappy comment: “Master of all he surveys. Look at my polls, ye Democrats, and despair.”

For his last-minute stab at a negotiated Iraqi withdrawal, Gorbachev got a down arrow: “Give back your Nobel, Comrade Backstabber. P.S. Your tanks stink.” Vietnam also got a down arrow: “Where’s that? You mean there was a war there too? Who cares?”

Neocon pundits, already dominating Washington’s chattering class, could barely contain their glee with the only caveat that Bush-41 had ended the Iraqi turkey shoot too soon and should have taken the carnage all the way to Baghdad.

The American people also rallied to the lopsided victory, celebrating with ticker-tape parades and cheering fireworks in honor of the conquering heroes. The victory-parade extravaganza stretched on for months, as hundreds of thousands jammed Washington for what was called “the mother of all parades.”

Americans bought Desert Storm T-shirts by the caseloads; kids were allowed to climb on tanks and other military hardware; the celebration concluded with what was called “the mother of all fireworks displays.” The next day, the Washington Post captured the mood with a headline: “Love Affair on the Mall: People and War Machines.”

The national bonding extended to the Washington press corps, which happily shed its professional burden of objectivity to join the national celebration. At the annual Gridiron Club dinner, where senior government officials and top journalists get to rub shoulders in a fun-filled evening, the men and women of the news media applauded wildly everything military.

The highlight of the evening was a special tribute to “the troops,” with a reading of a soldier’s letter home and then a violinist playing the haunting strains of Jay Ungar’s “Ashoken Farewell.” Special lyrics honoring Desert Storm were put to the music and the journalists in the Gridiron singers joined in the chorus: “Through the fog of distant war/Shines the strength of their devotion/To honor, to duty,/To sweet liberty.”

Among the celebrants at the dinner was Defense Secretary Cheney, who took note of how the Washington press corps was genuflecting before a popular war. Referring to the tribute, Cheney noted in some amazement, “You would not ordinarily expect that kind of unrestrained comment by the press.”

A month later at the White House Correspondents Dinner, the U.S. news media and celebrity guests cheered lustily when General Schwarzkopf was introduced. “It was like a Hollywood opening,” commented one journalist referring to the spotlights swirling around the field commander.

Neocon pundit Charles Krauthammer lectured the few dissidents who found the press corps’ groveling before the President and the military unsettling. “Loosen up, guys,” Krauthammer wrote. “Raise a glass, tip a hat, wave a pom-pom to the heroes of Desert Storm. If that makes you feel you’re living in Sparta, have another glass.”

American Hegemony

Like other observers, the neocons had seen how advanced U.S. technology had changed the nature of warfare. “Smart bombs” zeroed in on helpless targets; electronic sabotage disrupted enemy command and control; exquisitely equipped American troops outclassed the Iraqi military chugging around in Soviet-built tanks. War was made to look easy and fun with very light U.S. casualties.

The collapse of the Soviet Union later in 1991 represented the removal of the last obstacle to U.S. hegemony. The remaining question for the neocons was how to get and keep control of the levers of American power. However, those levers slipped out of their grasp with Bush-41’s favoritism toward his “realist” foreign policy advisers and then Bill Clinton’s election in 1992.

But the neocons still held many cards in the early 1990s, having gained credentials from their work in the Reagan administration and having built alliances with other hard-liners such as Bush-41’s Defense Secretary Cheney. The neocons also had grabbed important space on the opinion pages of key newspapers, like the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal, and influential chairs inside major foreign-policy think tanks.

The second game-changing event took place amid the neocon infatuation with Israel’s Likud leaders. In the mid-1990s, prominent American neocons, including Richard Perle and Douglas Feith, went to work for the campaign of Benjamin Netanyahu and tossed aside old ideas about a negotiated peace settlement with Israel’s Arab neighbors.

Rather than suffer the frustrations of negotiating a two-state solution to the Palestinian problem or dealing with the annoyance of Hezbollah in Lebanon, the neocons on Netanyahu’s team decided it was time for a bold new direction, which they outlined in a 1996 strategy paper, called “A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm.”

The paper advanced the idea that only “regime change” in hostile Muslim countries could achieve the necessary “clean break” from the diplomatic standoffs that had followed inconclusive Israeli-Palestinian peace talks. Under this “clean break,” Israel would no longer seek peace through compromise, but rather through confrontation, including the violent removal of leaders such as Saddam Hussein who were supportive of Israel’s close-in enemies.

The plan called Hussein’s ouster “an important Israeli strategic objective in its own right,” but also one that would destabilize the Assad dynasty in Syria and thus topple the power dominoes into Lebanon, where Hezbollah might soon find itself without its key Syrian ally. Iran also could find itself in the cross-hairs of “regime change.”

American Assistance

But what the “clean break” needed was the military might of the United States, since some of the targets like Iraq were too far away and too powerful to be defeated even by Israel’s highly efficient military. The cost in Israeli lives and to Israel’s economy from such overreach would have been staggering.

In 1998, the U.S. neocon brain trust pushed the “clean break” plan another step forward with the creation of the Project for the New American Century, which lobbied President Clinton to undertake the violent overthrow of Saddam Hussein.

However, Clinton would only go so far, maintaining a harsh embargo on Iraq and enforcing a “no-fly zone” which involved U.S. aircraft conducting periodic bombing raids. Still, with Clinton or his heir apparent, Al Gore, in the White House, a full-scale invasion of Iraq appeared out of the question.

The first key political obstacle was removed when the neocons helped engineer George W. Bush’s ascension to the presidency in Election 2000. However, the path was not fully cleared until al-Qaeda terrorists attacked New York and Washington on Sept. 11, 2001, leaving behind a political climate across America favoring war and revenge.

Of course, Bush-43 had to first attack Afghanistan, where al-Qaeda maintained its principal base, but he then quickly pivoted to the neocons’ desired target, Iraq. Besides being home to the already demonized Saddam Hussein, Iraq had other strategic advantages. It was not as heavily populated as some of its neighbors yet it was positioned squarely between Iran and Syria, two other top targets.

In those heady days of 2002-2003, a neocon joke posed the question of what to do after ousting Saddam Hussein in Iraq – whether to next go east to Iran or west to Syria. The punch-line was: “Real men go to Tehran.”

But first Iraq had to be vanquished, and this other agenda – restructuring the Middle East to make it safe for U.S. and Israeli interests – had to be played down, partly because average Americans might be skeptical and because expert Americans might have warned about the dangers from U.S. imperial overreach.

So, Bush-43, Vice President Cheney and their neocon advisers pushed the “hot button” of the American people, still frightened by the horrors of 9/11. The bogus case was made that Saddam Hussein had stockpiles of WMD that he was ready to give to al-Qaeda so the terrorists could inflict even greater devastation on the U.S. homeland.

Stampeding America

The neocons, some of whom grew up in families of left-wing Trotskyites, viewed themselves as a kind of a “vanguard” party using “agit-prop” to maneuver the American “proletariat.” The WMD scare was seen as the best way to stampede the American herd. Then, the neocon thinking went, the military victory in Iraq would consolidate war support and permit implementation of the next phases toward “regime change” in Iran and Syria.

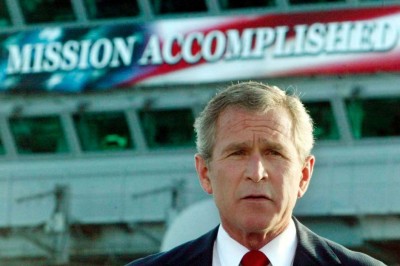

The plan seemed to be working early, as the U.S. military overwhelmed the beleaguered Iraqi army and captured Baghdad in three weeks. Bush-43 celebrated by landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln in a flight suit and delivering a speech beneath a banner reading “Mission Accomplished.”

However, the plan began to go awry when neocon pro-consul Paul Bremer – in pursuit of a neocon model regime – got rid of Iraq’s governing infrastructure, dismantled much of the social safety net and disbanded the army. Then, the neocon-favored leader, exile Ahmed Chalabi, turned out to be a non-starter with the Iraqi people.

An armed resistance emerged, using low-tech weapons such as “improvised explosive devices.” Soon, not only were thousands of American soldiers dying but ancient sectarian rivalries between Shiites and Sunnis began tearing Iraq apart. The scenes of chaotic violence were horrific.

Rather than gaining in popularity with the American people, the war began to lose support, leading to Democratic gains in 2006. The neocons salvaged some of their status in 2007 by pushing the fiction of the “successful surge,” which supposedly had turned impending defeat into victory, but the truth was that the “surge” only delayed the inevitable failure of the U.S. enterprise.

With George W. Bush’s departure in 2009 and the arrival of Barack Obama, the neocons retreated, too. Neocon influence waned within the Executive Branch, though neocons still maintained strongholds at Washington think tanks and on editorial pages of national news outlets like the Washington Post.

New developments in the region also created new neocon hopes for their old agenda. The Arab Spring of 2011 led to civil unrest in Syria where the Assad dynasty – based in non-Sunni religious sects – was challenged by a Sunni-led insurgency which included some democratic reformers as well as radical jihadists.

Meanwhile, in Iran, international opposition to its nuclear program prompted harsh economic sanctions. Though President Obama viewed the sanctions as leverage to compel Iran to accept limits on its nuclear program, some neocons were salivating over how to hijack the sanctions on behalf of “regime change.”

However, in November 2012, Obama’s defeat of neocon favorite Mitt Romney and the departure of neocon ally, CIA Director David Petraeus, were sharp blows to the neocon plans of reclaiming the reins of U.S. foreign policy. Now, the neocons must see how they can leverage their continued influence over Washington’s opinion circles – and hope for advantageous developments abroad – to steer Obama toward more confrontational approaches with Iran and Syria.

For the neocons, it also remains crucial that average Americans don’t think too much about the why behind the disastrous Iraq War, a tenth anniversary that can’t pass quickly enough as far as the neocons are concerned.

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his new book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com).